A Cayetano Retrospective: It’s The Economy, Stupid!

Benjamin Cayetano: First highest-ranking elected official of Filipino ancestry in the State of Hawai‘i: 10th in a series.

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran

Editor’s Note: 2019 marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the election of Benjamin J. Cayetano as the Fifth Governor of the State of Hawai‘i and the first Filipino-American elected as the head of an American state. This is the tenth in a series of articles profiling Cayetano and his historic election and service. Versions of these articles appeared previously in The Filipino Summit.

Going into the third year of his Administration, Governor Ben Cayetano and his cabinet—both formal and kitchen—faced the realization that while the rest of the U.S. was seeing some recovery, locally the economy remained stagnant. Following the conventional playbook for public priming of the economy, the Governor’s budget increased state infrastructure investments. But the government bond funded construction for highways, harbors and airport were disparaged by critics of cuts that the general fund budget shortfall had forced in social services and other operations. Along with the unprecedented measures undertaken to reduce or slow government spending—including what turned out to be a fairly modest reduction in the public workforce due to the requirements of civil service seniority but shocking to the government union membership—the Cabinet’s marching orders remained staying opportunistic in supporting economic growth.

No idea was necessarily rejected.

Called to take a site visit to Mount Leahi—a portion of State land shared by the Department of Defense’s Civil Defense headquarters and his Department’s Diamond Head State Monument, Land Board Chair Michael Wilson did not expect the proposal floated during that tour with the Governor, the Chief of Staff, the Budget Director and the chair of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA).

Wilson was vaguely aware that the State and OHA were discussing ways to settle the inherited and lingering dispute over the amount of ceded lands revenue owed by the State to OHA. As Wilson explained in shorthand to his deputy later that morning, Diamond Head was proposed as part of any land and cash deal.

But what surprised the DLNR Director, who had made his reputation in part based on his environmental advocacy to preserve Mount Olomana on the Windward side of the island, was the discussion moving to developing Mount Leahi as a golf course. As the group stood overlooking the plain of the crater—a grassy field that the National Guard sometimes used for parades—one of the group told the Governor to imagine teeing off from where they were and then taking a ski-lift like ride down to the fairway to hit their next shots.

The Governor was fairly skeptical but another in the group suggested that someone like an Eisner at Disney or another leisure destination visionary could be brought in to partner with either the State or OHA to create some kind of new economic attraction—not a Disneyland Hawai‘i but perhaps a golf course with some amenities to appeal to non-golfer members of a family.

The men recalled when Diamond Head had been the site of largescale concerts—something DLNR State Parks had been discouraging from re-occurring as they tried to turn the Monument into a more natural wilderness park with a fairly safe hike to the rim.

The proposal was panned by local pundits when it was reported shortly afterwards.

But the incident reflected the willingness of the Cabinet to consider all manner of economic development to lift Hawai‘i out of the doldrums.

Gov. Cayetano had plucked from the University of Hawai‘i Seiji Naya to head his Department of Economic Development and Tourism (DBEDT). Naya was Japan-born but brought to Hawai‘i Nisei soldiers supporter Earl Finch in the 1950s. Dr. Naya did not look it but he was also a 1984 inductee to the UH Sports Hall of Fame, having won NCAA featherweight boxing titles as a UH undergraduate in 1954 and 1955. After earning a Ph.D. in Economics from the University of Wisconsin in 1965, he returned to the University of Hawai‘i to teach. By 1995, Naya had already enjoyed a well-regarded career in international economics and Asian development, including a stint as Chief Economist at the Asian Development Bank in Manila in the 1980s. By the time he joined the nascent Cayetano Cabinet, no one would have suspected the professorial Naya as a former champion pugilist. His comments to others in the administration and advice to the Governor were usually measured but quietly firm and persistent in his areas of interest and expertise.

Naya and his DBEDT deputies had pushed legislative proposals to support growth in selected sectors and had been providing support to the Governor’s staffers charged with niche projects ranging from digital media and motion pictures to pursuing aircraft maintenance, expanding private ship maintenance, and proposing tree harvests and reforesting former sugar lands. But as DBEDT wrote in a special 1998 edition of its quarterly report, “Virtually everyone in Hawai‘i has been impacted by the slow growth in the State’s economy over the last six years … There were about 12,000 fewer jobs last year than in 1992 … All of this has taken place against the backdrop of one of the strongest economic expansions in U.S. history, an expansion shared by virtually every state except Hawai‘i.”

The need to address the lagging economy was not lost on the Governor’s political circle. With little growth to show from the administration’s uncoordinated economic expansion and recruitment work, informal discussions with legislative leaders Senate President Norman Mizuguchi and House Speaker Joseph Souki, public worker union heads and the Governor’s kitchen Cabinet led to the idea of convening key stakeholders from various parts of the community to look at the fundamental structure of Hawai‘i’s economy and to propose changes.

Former House Speaker Souki recalls two early movers were State Senators Les Ihara and Carol Fukunaga: “They both approached [Senate President] Norman [Mizuguchi] and [me] on the idea—getting a cross-section of the community, bankers, hotel executives, labor, higher and lower education [stakeholders], and lawyers. With that we approached the Governor if he would be interested in being a co-chair—the other two were Norman and me. Ben bought the idea and we spent the whole summer debating economic alternatives.”

As DBEDT described the thinking, “the leaders [of the effort] recognized that major economic reforms were needed and that formulating and enacting such reforms would be possible only through a large, cooperative effort involving segments of the community knowledgeable in how Hawai‘i’s economic and business system works.” When Gov. Cayetano agreed to convene a blue-ribbon panel to recommend economic changes, Dr. Naya, along with his DBEDT deputy Brad Mossman, got tapped to support the effort. Deputy Director Mossman, equally reserved as his boss but on the younger end of middle aged, would lead the DBEDT staff support for what became the Economic Revitalization Task Force (ERTF). Bank of Hawai‘i and Castle & Cooke executive Tom Leppert and Hawai‘i Justice Foundation executive director Peter Adler were enlisted as facilitators for the Task Force. The small cadre planning the process included Lt. Gov. Mazie Hirono, Joe Blanco from the Governor’s Office, Senator Les Ihara, Sen. Mike McCartney, Director Naya and Deputy Mossman, Rep. Tom Okamura, Rep. Marcus Oshiro, Office of State Planning Director Gregory Pai and the Governor’s Chief of Staff Charles Toguchi.

Eventually, the Governor and others in the Bishop Street boardrooms and small business centers on the neighbor islands, coaxed the participation of over two dozen fairly impressive who’s who in the island business community. The task force members included J.W.A. “Doc” Buyers from C. Brewer, John Couch from Alexander & Baldwin, Robert Clarke from Hawaii-an Electric, John Reed from DFS, Charles Kawakami from Kaua‘i’s Big Save, and Barry Taniguchi from the Big Island’s KTA Superstores. From the financial sector, both Walter Dods from First Hawaiian and Larry Johnson from Bank of Hawai‘i served. Visitor Industry stalwarts Richard Kelley from Outrigger, Stanley Takahashi from Kyo-Ya Company, and Roy Tokujo from Cove Marketing participated. Labor leaders included Eusebio “Bobo” Lapenia from the ILWU, Russell Okata from HGEA, Gary Rodrigues from UPW, and Bruce Coppa from the Carpenters Union’s Pacific Resource Partnership. University of Hawai‘i President Kenneth Mortimer and Hawai‘i Pacific University President Chatt Wright also sat on main panel. Lawrence Fuller from the Honolulu Advertiser, Stanley Hong from the Chamber of Commerce, Patricia Loui from Omnitrak Group, retired businessman Donald Malcolm, Diane Plotts, and Stephany Sofos rounded out the members besides the Governor, Senate President and House Speaker.

Along with ERTF members, working groups on specific topics were also convened. As Mossman recalls, the working groups and then the ERTF itself took several months to come up with a report. Part of the time was spent recruiting members, holding working group briefings and meetings, and then drafting recommendations for the ERTF to consider. The aim had been to hold deliberations and reach consensus in the late Fall of 1997 so that proposals could be drafted for the 1998 Legislative Session. In his autobiography, Gov. Cayetano described, “The members agreed that each recommendation had to meet two conditions: It had to be bold or, as Leppert put it, something that “flew at the 30,000-foot level,” and it had to be feasible, something that could be implemented quickly and not take years to gain public approval.” The ERTF also agreed to operate by consensus—only proposals unanimously supported would be included in the package submitted for legislative consideration.

DBEDT in its report argued that the ERTF developed “a set of recommendations that all members considered bold, meaningful and achievable.” It also suggested “by a large margin most of the criticism appears to be from those who believe the Task Force went too far in one or more directions.” As Mossman laconically recalls, “the basic thrust was fairly radical.”

Given the expanding role of tourism in the State’s economy, the ERTF agreed on the need to address “the level and uncertainty of funding for tourism marketing and promotion.” On the heels of the first Gulf War and then the hurricane that hit the island of Kaua‘i, the post-Statehood expansion and strength of the Visitor Industry had slowed and contributed to the State’s difficulty in recapturing the rapid post-World War II economic growth. While the Holy Grail of diversification of the local economy could not be ignored, given the size of the Visitor Industry, the ERTF believed “tourism is also where positive changes are likely to have the largest effects.”

Given the presence of private sector businesspeople on the working groups and ERTF, recommendations were also made regarding regulatory reform—how the State pursued recognized public goals of a clean environment, safe workplaces and other health and welfare goods—and efficiency—reducing the costs of government providing services to residents and businesses.

The ERTF also looked at improving education, “the key to long-run economic success.” Recommendations were included for both the public schools and the University of Hawai‘i. For the school system, the ERTF proposed County-based school boards. While education standards would be set at the State level, the means for achieving those goals would be determined at the County level. Budgeting would also be more school-based. The ERTF also proposed requiring both a second language and computer literacy with the latter supported by private sector investment in school network technology.

For the University, the ERTF included long-sought “autonomy” from legislative and executive oversight: “Restructure the University of Hawai‘i into a quasi-public corporation with independent accountability.” Act 115 (1998) provided UH more autonomy. Maui upcountry Rep. David Morihara, then-House Higher Education chair, called the bill a “big win.” The bill weaned UH leaders from oversight by the state and capped UH President Mortimer’s efforts to win the university system more control over its affairs. The University Board of Trustees would be charged with determining fees without going through the process required for all other State agencies. The new law also allowed UH to hire its own lawyers rather than depend on the Attorney General’s office.

Cayetano executive assistant Joseph Blanco recounts, “Having served two terms on the UH Board of Regents, one of the lasting outcomes of the ERTF was Governor Cayetano used the power of his office to give the University of Hawai‘i Constitutional Autonomy. The governor secured support from two-thirds of the legislature to pass a constitutional amendment and then ensured that ballot initiative passed with overwhelming public support. Those efforts culminated with the passage of Act 115, which is one of the most significant milestones in the history of the University of Hawai‘i.”

Cayetano executive assistant Joseph Blanco recounts, “Having served two terms on the UH Board of Regents, one of the lasting outcomes of the ERTF was Governor Cayetano used the power of his office to give the University of Hawai‘i Constitutional Autonomy. The governor secured support from two-thirds of the legislature to pass a constitutional amendment and then ensured that ballot initiative passed with overwhelming public support. Those efforts culminated with the passage of Act 115, which is one of the most significant milestones in the history of the University of Hawai‘i.”

Finally, and at the core of the ERTF member’s discussions about the Hawai‘i business climate, the Task Force raised addressing Taxation. As DBEDT described the direction, “[Hawai‘i] must reform the tax structure by lowering tax rates and following other jurisdictions in moving away from taxation of income and toward the taxation of consumption.”

The ERTF proposed raising the Transient Accommodations Tax (or State Hotel Room Tax) and dedicating a portion towards tourism promotion efforts. It also proposed creating a tourism executive board with geographic representation to oversee all marketing and promotion. Act 156 (1998) would create the Hawai‘i Tourism Authority, consolidating most of the state’s diverse tourism-related activities in a single entity and providing a portion of the Hotel Room Tax to fund its activities. The new law also expanded application of the hotel room tax to timeshare units.

In Mossman’s assessment two decades later, the longest scale impact from the ERTF arose from the creation of the Hawai‘i Tourism Authority. The dedication of hotel room tax revenues provided resources that improved promotion, based on more research and data on markets. The changes also rationalized convention center payments. Under the more diffused situation then existing, when East Coast visitors dropped off, the different island visitor bureaus, hotels, and visitor-dependent businesses did not have the ability to coordinate efforts to make up for the losses. The HTA was also structured to have broader representation of the visitor industry than just the Waikiki hotel leaders.

The ERTF argued for imposing timeframes on review and approval for all permits and licenses by County and State agencies. The ERTF also proposed eliminating the State Land Use Commission (LUC) and transferring its responsibilities to the Counties and the Land Board. One Cayetano sub-Cabinet appointee to the diminished Office of State Planning had accepted a LUC seat and then learned of the ERTF proposal. Eventually, the regulatory changes adopted were largely incremental. While the task forces and the ERTF looked at eliminating duplication of services—including roadway maintenance, civil defense, human services, parks operations—between the State and Counties, when studied, only modest savings were projected with costs just shifted from one jurisdiction to another. Act 230 (1998) tasked a special committee to “transform” state government’s budgeting, accounting, and procurement system, including shifting to performance- based budgeting. The same law created another special committee to foster public-private competition for state and county government services. Act 164 (1998) would impose a general requirement for automatic approval of various government approvals and permits that did not meet a time deadline for reviews.

Given the looming 1998 elections, although ERTF included both moderate-Republicans and key business executives from both major firms and small businesses, the Hawai‘i GOP leadership for what the Governor and his supporters saw as clearly political reasons, opposed the ERTF tax proposals. As Mossman saw it, the ERTF effort made it harder to attack the Governor for not doing anything about the economy—instead, he proposed some fairly large changes to the way Hawai‘i did business. Mossman points out that seventy percent of the ERTF recommendations passed in one form or another.

But another drawback of the Task Force was the composition of its membership. While the notion was to bring in a group knowledgeable about Hawai‘i’s business climate—those most directly involved in the economy and business—the legislative process provided an avenue for protest and dissent for those left out of the formal ERTF work. Legislators also introduced measures aimed at other issues—for example, measures borrowed from Silicon Valley aimed at spurring growth of the technology sector. And as Governor Cayetano and the former legislators on his team understood, and certainly the legislative leadership, the administration proposes but it was the legislature that disposes. Even with the ERTF process originating with legislative leadership, the committee system and political calculations of the individual members would also come into play. As Governor Cayetano wrote in his memoirs, “In 1998, the ERTF became too much of a risk for Democratic legislators, the majority of whom faced reelection campaigns less than a year away. The House, under Speaker Joe Souki, was still holding firm, but the Senate, under Norman Mizuguchi, had begun to waver.”

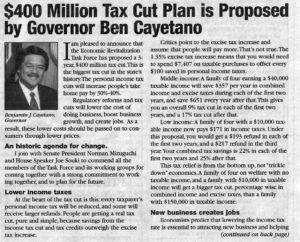

As might have been expected the tax proposals proved the most contentious. As then-House Speaker Souki recalls, “A big one was to raise the excise tax and lower the state income tax [rates].” Changes proposed included reductions in the income tax rates coupled with an increase in Hawai‘i’s broadly applied general excise tax. The proposals also included creation of two low-income tax credits and cutting corporate tax rates. While the ERTF recommended hiking the GET from 4% to 4.7%, they also included an exemption for exported services with a Use Tax on imported services. Act 157 (1998) provided income tax relief by reducing tax rates over a four-year period and by establishing a low-income tax credit. Act 71 (1999), adopted in the post-election session, followed up with de-pyramiding the General Excise Tax by reducing the GET assessment on wholesale sales of services.

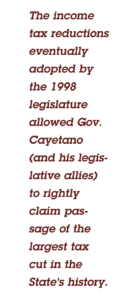

The income tax reductions eventually adopted by the 1998 legislature allowed Governor Cayetano (and his legislative allies) to rightly claim passage of the largest tax cut in the State’s history. The GET proposals failed due in large part to an outcry regarding the regressive impact of the proposed hike—lower income people paid more of their resources for goods and services subject to the GET—even though a fairly large proportion of the GET was exported to and borne by island visitors. As Governor Cayetano recounted in his memoirs, the public sector union leaders wanted any tax changes to be revenue neutral. Any drastic reduction in revenues would have limited government leaders choices in balancing operating budgets and likely impacting future collective bargaining negotiations.

The Task Force also raised the need to address Hawaiian claims and self-determination, although it admitted that the ERTF effort “might be counterproductive to make specific recommendations at this point.” Other than a tepid statement noting the need to address those long-standing historical wrongs, the ERTF made no specific proposals towards addressing the issues.

The ERTF members and supporters mounted a PR campaign in favor of the tax recommendations and some even organized some sign waving around the Capitol. Neither effort was met with much enthusiasm by the general public. “Privately, I knew we had lost the public relations battle,” the Governor recalled in his memoirs. “My heart went out to Leppert and the other ERTF members who had attended meeting after meeting and spent countless hours trying to explain the proposal.” But Governor Cayetano and his administration persisted, adapting as the legislature reacted to the public lobbying on the various measures. He would call on the legislature to extend the session to continue negotiations over a number of the ERTF-related bills, including taxation, civil service reform and privatization. Near the end of the session, he proposed de-coupling the income tax reductions from the GET increases, allowing the controversial consumption tax portion of the ERTF tax restructuring to die.

The ERTF package allowed the legislators to return to their districts touting some significant changes aimed at improving the islands and resulted in most winning re-election. “Most of the recommendations passed the legislature and became law,” Speaker Souki notes, “Except for the raising of the excise tax, however the legislature led by the Governor lowered the state income tax.” But Souki noted that in retrospect, simply reducing income taxes proved costly, resulting in a two billion-dollar deficit some years later. “Trickle down theory does not work,” Souki ruefully observes.

In some observers’ view, the ERTF process eventually led to some casualties among the legislative champions of the effort—Speaker Souki would lose his leadership position to his Finance Committee Chair Calvin Say, supported by newer members critical of the aborted GET proposal and the perceived heavy-handedness of the House leadership and President Mizuguchi would lose enough allies to also step down. However, the Task Force work helped Governor Cayetano blunt the main argument of his GOP opponent in the 1998 election. Maui Mayor Linda Lingle argued that change was needed; Cayetano could say he had been actually working to make changes and had won some of the changes promising better days ahead. As one of his official biographies later recounted, “confronted with a storm of criticism and opposition from factions opposed to his proposed reforms, Governor Cayetano nevertheless implemented civil service reform, reduced the size and growth of the state government to less than the rate of inflation, pushed through and implemented one of the biggest reduction of state taxes in the nation at the time, built a record number of public schools and homes for native Hawaiian homesteaders, constructed a new state convention center to boost tourism, a new state art museum and began construction of a new medical school-research center for the University of Hawai‘i.”

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran served in the Cayetano Administration. He presently is the State Senator from Central Maui.

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran served in the Cayetano Administration. He presently is the State Senator from Central Maui.