Editor’s note: The following is excerpted from Christine Sabado’s soon-to-be published memoirs. The Sabados celebrated their 49th wedding anniversary on June 14.

As we were about to enter the little plantation house, my nervousness overwhelmed me. Perhaps it was the moment but suddenly the perfume of the profusion of flowers and the orchids that lined the porch embraced and absorbed me. I paused on a step crusted with the russet soil of the fields and looked to the man who would be my husband. Our eyes locked in the moment. Stuttering at first, I swallowed hard and caught my courage and centered it in the moment to whisper “This is it then, if we don’t work out, you cannot bring another girl to meet the family.”

Photo courtesy Sabado ‘Ohana

Philip was jittery as he stuttered and struggled to make the formal introductions. Everyone had frozen in place as his sister and nieces peered over each other at the kitchen door, all eyes watched to see how this was going to go.

Photo courtesy Sabado ‘Ohana

I could see that to them he was their treasured jewel. The youngest of twelve children, he was the buridik, the favored son. Finally, under his mother’s proud and loving gaze, Philip blurted, “Ma, dis Christine, my friend.” He stopped abruptly, seemingly unable to go on, time was suspended as we waited for Mama’s reply. She lifted her head to see me as her dark penetrating eyes saw into mine. Her voice was clear and her first words in broken English would never leave me.

“My son is a poor boy… And you are not, why you like marry him?” She did not pose the question in an arrogant or aggressive tone it was simply a question.

My answer came without pause and still makes me stop and reflect on the wisdom I was given on this day, “Yes, that may be true, but he will not always be a poor boy, will he? Things will change.” Her response was immediate as she cupped her hand to her mouth; a smile creased her frail face as she gave a knowing chuckle.

Photo courtesy Sabado ‘Ohanap

The next evening, Philip was asked to go to his parents’ room to talk story. It seemed he was with them for hours. I was so anxious; I grew weary and succumbed to the long day and drifted off into a deep sleep. I awoke when a lone beam of light from the hallway filled the room like an arrow seeking its mark. He opened the door slowly to check if I was still awake.

I sat up immediately and pulled myself together, trying to sit poised and natural, even though I was as nervous as if I’d been on my first date. When he did not speak, I grew impatient and blurted, “Did they like me? Am I okay? Your Mom is sort of spooky but your Dad is really sweet. Hmmm, I don’t think your sisters like me very much.” When he still did not answer, I demanded “Tell me now.” My mind reeled. After all, what had they been talking about so long? I was so anxious; I must have sounded like a fast train that had derailed with my wheels spinning in the air.

He smiled in his innocent way, laughing at me, as always and rolling his eyes “Too late to back out now. They are going to start fattening the pigs!”

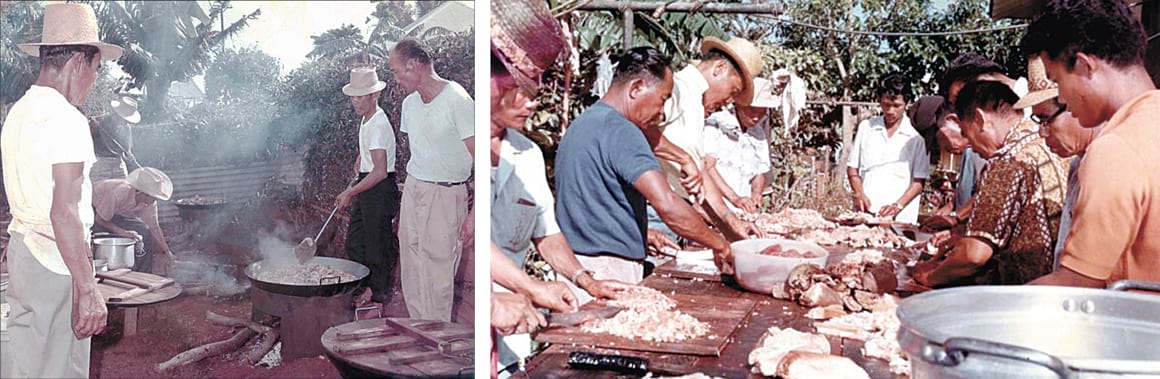

The question of how many pigs, cows and chickens would be required for cooking at the party was a critical point. Most of the talk at the table from there on revolved around this main topic. Many nights were spent in serious discussion about whose pigs and cows to buy. How much garlic and bay leaf would be needed? Not to mention the quantity of dishes served. I was amazed and stood back with true awe to observe the intense planning and discussions that revolved around the party. A main point discussed was about who would hold the honor as the main cook—the Luna—the boss who would call the shots in the end. His pay was Seagram’s 7 whiskey; enough for himself and his crew.

Photo courtesy Sabado ‘Ohana

All of this organization was a science for them. This Filipino family loved nothing more than a good party. In the end we had three pigs (more than nine hundred pounds of pork), ninety-five chickens and two cows, for a guest list that would top off at over fifteen hundred people—a significant amount of Molokai’s population.

June fourteenth was chosen after a great deal of discussion, choosing the correct date for the wedding was quite strategic, an ordeal as well. Many superstitions played into this decision. Naturally it was understood Mama would have the final word. A mix of the Chinese calendar as well as calculating pay day was crucial. It was understood that all the townspeople would be in a more comfortable position to kōkua if they were not between paychecks.

My family in California ordered formal wedding invitations on a beautiful white linen paper from the finest printer in Los Angeles. These were sent to the mainland guests, friends of my parents and people I had known since I was a small girl. I received a box of the invitations with the double envelopes as well. They were all so white and beautiful. I laid them out proudly for my husband to see. For a moment he looked perplexed and then asked innocently, “Why send? Everybody going come.” And so they did, all fifteen hundred guests. Only my parents, my sister, and Nanny (my paternal grandmother) came from my side.

Photo courtesy Sabado ‘Ohana

As the wedding day grew near, my mother arrived from Los Angeles, we were given a shopping list a mile long. On this ever-growing list was enough garlic, bay leaves and onions to sink a ship. An especially important item on the list was whiskey for the cooks; it had to be Seagram’s 7. The preferred drink was called a ‘seven, seven’ a mix of Seagram’s and Seven-up; the mix was probably more whiskey than soda.

Photo courtesy Sabado ‘Ohana

Parties are major events in the Filipino community. The centerpiece of every party was the food and the eating. When I sat down to eat, everyone would find a reason to pass by me and look at my plate to see how brave I was in trying his or her foods. As I ate, they smiled and laughed, cupping their hands over their mouths or revealing their many gold teeth. Their comment was always, “Ai yah, ading (Oh my, young one), you eat dat one? Ai yah!” Technically the ice was broken as they laughed and talked, saying, “No more da Haole eat dis kine, you one Filipina now.” It was so simple; I was accepted because I ate their food. This was always the first step.

There was one secret I would keep past my wedding day. I was already two months pregnant with our first child; it was imperative that two people were kept ignorant of this fact. One was my Irish-Catholic father who was devout and very traditional. My father’s Irish Catholic ethics still reined and ruled in our home. The other to be kept uninformed was the Belgian priest who would marry us.

Philip’s family was elated about my pregnancy; babies were the complete epic-center of their life. I was sternly warned not to tell the priest. With wide cautious eyes my soon-to-be sisters in law admonished, “Be careful not to appear sick or pale, he will find out.” This advice made me stop and laugh because, as I saw it, with my fair Irish skin and freckles, I was always pale to them!

There was an infamous story about a woman from the camp who told the priest of her being with child before the ceremony and they were forced to be married on the church steps. In the eyes of the church she was considered tainted as well as contaminated and could not enter the holy ground. I was horrified! To think if my parents and my Nanny had come all this way, only to see me married on the church steps! I was committed to keeping this secret.

Photo courtesy Sabado ‘Ohana

The preparations for the wedding seemed endless. I was not ready for the amount of ritual and superstition that preceded the sacred event. Mama set forth the first directive. In the next seven days before the wedding, Philip and I had to be separated, unable to see each other until we met at the church steps. All of these superstitions and precautions were to ensure we would have prosperity, health, many children and long happy years together.

To guarantee our paths would not cross, Philip was taken to stay at a hidden location at the opposite end of the island, while I remained in Maunaloa. He was not allowed to drive a car (considered to be bad luck). I am not sure he really minded this custom because most of his time was spent with the other men hanging out, drinking, joking and gathering flowers and the special foliage that would be needed to decorate the wedding hall.

Somehow they were very careful about timing and managed to keep us on opposite ends of the island. This was amazing since there were only five-thousand people living on this island then.

As all love stories go, we managed to find each other once; it would be at his niece’s home near the harbor on the beach. For some reason in these seven days everyone was off and gone. I was uncharacteristically alone and then he was there; it seemed surreal, was this a dream? To this day, I am not really sure that this actually occurred. We made wild passionate love in minutes and then a car drove up and he was gone. Then I was back and secure at the camp, with numerous dress fittings and predictable details.

At the time of the separation, the family met relatives and drove Philip everywhere. Each time he was taken to the airport a carload of family arrived from another island. This proved amazing since no invitations were sent to his family. They all just showed up. The coconut wireless was their means of communication and was now on high speed. Often a relative just walked off the plane at the airport and said to Phil, “I am your cousin from Lāna‘i; we have never met. I am on your father’s side; I am here to help prepare for your party.” It was their custom and a responsibility to be there as family to support each other in this new land during both the sad times (a death) and happy times (a marriage or birth). In the end there were well over fifteen hundred people at the reception and the four from my side of the family.

During this period, there was the final selection of the pigs and cows for the party food. My father was in paradise as his lifetime hobby and passion was photography. He took pictures of every moment from our wedding down to the preparation of the pigs. As custom dictated, a pole was set in the pig’s mouth to hold the pig down and all four feet were bound as well. A sharp knife was then thrust into the heart. Immediately a cooking pot was placed under the punctured heart as it spewed blood. Pot after pot collected the liquid which moments before was the life force of the now squealing and kicking animal on the makeshift table. The blood was taken to the side to be mixed with vinegar and cooked into a dish known as dinardaraan. The vinegar helped to cook the blood. Some of the older men took cupfuls of the still warm liquid and drank the vinegary brew on the spot.

At this auspicious time, another practice was to drink from the bitters bag, the gall bladder of the animal. Obviously, this was a very cultural tradition. I never learned why all of this was done. What I saw in my father’s photographs was a great deal of bravado and camaraderie. The combination of the Filipino world and the Hawaiian nest where we flourished made this time ever sweeter.

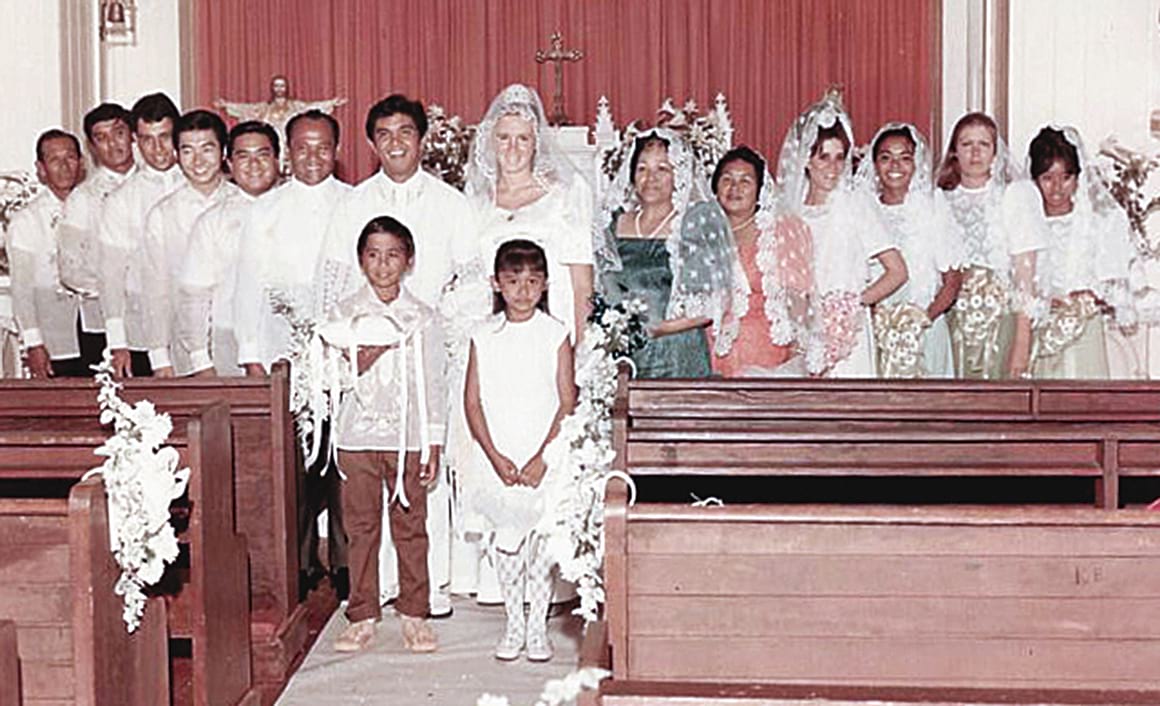

Long-established traditions would herald that every detail and protocol was to be followed in the days to come. Philip’s sheer richly embroidered wedding shirt was called a Barong Tagalog. It was made of a traditional fabric known as piña; a smooth almost stiff fabric made from the pounded fibers of the pineapple plant. Rows and rows of white floral embroidery decorated the front panels of the ecru button-down shirt. All the male attendants wore the traditional embroidered shirts as well.

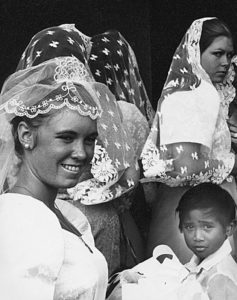

My wedding gown was a delicate white 100% Japanese silk with small floral designs woven into the weave and texture of the fabric. The style was the traditional Filipino dress called Terno, with peaked, rounded sleeves. The style was probably from the 1800s with a strong colonial Spanish influence. Years before I had seen photos of the Marcos’ when they reigned in Manila. I remember Imelda’s dresses; all the glittering gowns in every color had the same stylized sleeve.

My four attendants were dressed in shades of green silk, all sea foam colors. Lace mantillas complimented the overall Spanish influence. They all wore white lace bolero tops; the pale green shades of the dress peeked through the lace tops. Their dresses had the same peaked Filipino sleeves that kept with the tradition.

We chose to wear the traditional Filipino wedding attire in honor of Mama and Papa; this was not a hard decision, I was already enchanted with all that I’d seen. Why not go all the way? So many young couples in the camp had adopted Western ways. Later I realized we were perhaps one of the last couples in the family to be traditional; all who followed chose to be Western in their dress, with store-bought white lace and seed pearls. We were proud to keep up the traditions.

Selected women of the camp sewed my dress and the attendants’ dresses and mens’ shirts by hand. They all sat in a circle and sewed happily for months. There was no money involved; this was done for the sake of the celebration and out of respect and love for Philip and his family. Someone or many were silently behind the scenes making sure all was accomplished on time; it was like an army in the background moved silently to organize the food, clothing, and party details for over a thousand people. Lucky I was so young, I would have been clearly overwhelmed. Instead, I just happily followed along.

The other tradition that was mandated was to have Godparents, known as Ninongs and Ninangs. This was in addition to our bridesmaids and attendants that were a Western custom. The Ninongs and Ninangs are the sponsors for the bride and groom; it was an honor to be asked to be a Godparent. The bond and commitment to each other is life-long. In their language, as well as Spanish, these special people are forever known as Compadre/Comadre. All told, we had ten attendants on each side. The space at the altar was full and appeared crowded as we stood for photos. A snag occurred when the elder Ninang was chosen to stand by my side. My sister threw a fit and pulled rank and insisted she be by my side. This created an impasse until Phil’s brother volunteered to take the same position, standing next to his brother on the opposite side. When it came to these cultural precepts there was not much flexibility. This slighting was the talk of the island and intriguing, as it was a collision of western and Island traditions.

On this auspicious day the cooks began at four in the morning, prepping and cooking all the ‘cut meat’ in a large silyase (large black woks) that were placed over open wooden fires of kiawe wood, a mesquite, which grew profusely in the area. All the cooks were jovial older men, who were without a care in the world. There were many younger men who were willing assistants, as apprentices. The young men cut the meat and observed the masters. Breaks were taken every hour for a shot of the favored seven-seven. By the time the food was served they were all a jolly group. There was no need to pay these exceptional cooks; the camaraderie of the cooks and the joy of booze, family and the community was enough. Their mood and their jovial happiness made for an even better time; I cannot understate that they lived for these moments, these special times and parties are the grist to their lives.

On the wedding day Philip returned to the camp early; I suspected he had been at a sister’s house. As tradition dictated, he was to remain hidden from me till the moment we would meet in the church, ready to walk down the aisle. Everyone was frantic on this day and yet there was one last task to be completed but it was bad luck for him to do any labor on the wedding day. On the opposite end of the camp, he ran from house to house searching for an iron and someone to press his white wedding trousers. With a melodic whine he would plead: “Excuse me, Nana, could you press my pants? My sister was cooking for the party… and forgot.” There would be no takers, “Aye ya, so sorry boy, I no more ir-ron, see you at the party.” He then ran to the next house to hear the same thing. Finally, by the fourth or fifth house, he found an iron and someone to do the chore.

On this auspicious day, I walked down the same red dirt road that Philip and Mama had trodden as a boy. I wobbled on my white satin heels as my perfect white silk train trailed in the red Molokai dirt. On my head was placed a white Spanish comb, fixed into my chignon, the cluster of pearls and small diamonds sparkled in the sun. For the veil that swept to the ground, I chose the sheerest lace with a small scalloped design on the border. Years later both my daughters would wear the same veil on their special days.

In my hands were twenty strands of pikake (jasmine) blossoms mixed with sweet vanilla white honohono orchids, the most fragrant flowers in the world. The flowers were also strung in lei chains as long as my dress.

Only fifty or sixty guests attended the ceremony at St. Vincent’s church; everyone else was at the hall. My family, being Irish-Catholics, requested a High Mass. I am sure our other guests wondered why we tarried so long at the wedding since everyone else, including Philip’s parents, were waiting at the hall for the party to begin.

As I entered the church, I saw a white meat-packing paper laid down the aisle from the door to the altar. As I walked down the aisle, the red dirt made tracks and the tips of my heels made small holes in the paper. The wind swept through the small wooden building in a funnel and picked up the edge of the paper. Suddenly the white butcher paper was whipped into the air, making a crackling noise as it flew over our heads. I turned completely around for a brief moment to see what was making all the commotion; I was aghast, no one else seemed to notice. An entire sheet of white butcher paper, the length of the church aisle literally flew and rippled onto the ceiling. Apparently, these things were normal in the camp and everyone smiled when they saw my face as I watched the butcher paper crackle and buckle, scraping the ceiling of the small, white wooden church.

The priest was a kind man but he had the annoying habit of forgetting my name during the ceremony. He recited the vows, “Do you… uh… what is your name again?… take this man…” After the third time he forgot my name, I was annoyed. Every time, he hit the blank, I filled it in with a stern whisper: “My name’s Christine.” He was nervous and did not hear me. The organist at the opposite end of the church only knew the first bars of Here Comes the Bride and played it twenty times in a row. It was like a comedy that only I was seeing, how could I break out in the giggles as I stood at the altar? In truth, it was charming and the pictures show how we were beaming.

Once our vows were exchanged, Philip and I shared a kiss and then turned to face the open doors that revealed the miles of rolling pineapple fields with Molokai’s grandeur before us. Someone was kind enough to catch the naughty white butcher paper that had run amok and held it in place for us as we walked down the aisle. Outside the church my mother was wiping her tears of happiness as we began the walk to the hall. Just as I began to wonder where everyone was, I saw a sea of people before me. They all stood at the ready, to greet the bride and groom as we passed. It was like a parade, where all the people line the road as we walked from the church on the hill. Fifteen hundred people stood on the road waiting for us to arrive so the party could begin. The women cried, waving and wiping their tears and the children beamed, jumping with joy. I recognized some of the women who had sewn my dress. They tugged at my sleeve as I passed them. One last adjustment! I had never seen so many people in my life; neither, I am sure, had my family. Among the crowd were Philip’s school chums and his aunts, uncles and cousins having many different nationalities; they all smiled, jumped and clapped as we passed. Before we reached the hall, which was really an extension of the camp post office, we were met by an overwhelming fragrance of fresh, just-picked flowers and maile, a green vine that is picked traditionally with long sharp fingernails to carefully snap the vine, releasing the potent aroma. The sweet-smelling maile whose slender green leaves and long thin stems are looped and twisted in a careful fashion, now adorned every corner of the hall.

My spouse’s family and town mates had charmed the plantation room and transformed the red dirt-stained walls into a floral palace for the reception. The hall was completely decorated with strung flowers and maile, all gathered from the Molokai forests. The flowers which Phil had gathered for days from the mountains were also twisted into the maile. Someone from the camp had woven a large roll of flowers that took two hands to hold. They held special flower lei of a unique weave made from the rare purple Maunaloa flowers, which are only found in this area of the mountain. The wedding party and immediate family members each received these special lavender-and-white lei to wear during the party.

Photo courtesy Sabado ‘Ohana

It was the custom at that time for the groom’s family to pay for the wedding and the party. One of Philip’s sisters gave us 200 pounds of rice. The pigs and cows were gifts as well. My Mum provided all the whiskey for the cooks. Philip’s brother Eugene bought our wedding cake from Kanemitsu Bakery in Kaunakakai. Before the wedding there was so much fussing and whispering about the cake and my curiosity was aroused. When I pressed the point, I discovered everyone was concerned about the condition of the cake when it reached the camp. The biggest worry was it might not survive the distance from the island town to the mountain village intact. Because the roads were bumpy, this was a valid concern; more often than not a cake arrived in Maunaloa broken, or worse, with flies stuck in the frosting. Fortunately, our cake arrived in one piece and… without flies.

I bought the cake top decoration in Honolulu at a Portuguese bakery. As I looked at the top shelf above all the cold glass displays of cakes and pastries, I considered the many styles of cake decorations, almost all had the lace trim that would quickly yellow in time. Finally, I chose a couple, arm in arm, under a heart-shaped arch. The problem was they were both blonde with the pinkest plastic skin. I took felt tip pens and colored the groom’s hair black and tinted his pink face to bronze. (I guess I was a pioneer in interracial wedding cake tops!) It suited me and everyone wondered if I had it special ordered. My answer was a smug smile and a silent thank you to Mom, for all those art classes on Saturday mornings.

My mother still tells a story about how we ran out of paper plates during the party. (She had bought 1,000 paper plates.) All the plates were used and midway through the party the shopkeeper opened the store especially for her so she could buy an additional 500 plates. In the pictures many of the guests seem to be carrying a small cooking pot from their own kitchens to take home to feast on leftovers.

In one corner of the room, a shot table was set up. Money was placed in a freshly oiled koa bowl in exchange for a shot of whiskey. This was a busy table, with a long line. An ensemble of old men with their instruments provided the orchestra music. Even their name was romantic and melodic, they were known to all as a Rondalla band. The origins of this instrument stem from the minstrel days of renaissance Spain; this was more commonly known as a mandolin.

My brother-in-law Eugene was the closest in age to Philip and a professional dancer. He was a star performer of the same Pearl of the Orient Dance Troupe that Phil had been a member of. The very same dance troupe I’d seen all those years ago when I sat in the front row as a teenager. Eugene brought some fellow dancers to Molokai from Honolulu as they danced in the traditional Filipino attire in perfect harmony. I couldn’t have been more grateful of their contribution to our wedding day. Together Philip and Eugene taught me some of the traditional dances. Philip was already seasoned and I was a work in progress that never felt in sync; they would laugh heartily at all my attempts to work my two left feet. I am convinced I am a terrible dancer and it took courage and enormous effort for me to do the dances at all. When I showed Eugene and Philip I could dance an Irish jig, they looked at each other, confused. “If you can dance like that,” they asked, “why is this so hard?”

Eugene and my former housemate Diane performed a romantic Maria Clara dance from the Spanish era. The flirtatious dance took them about the room; it was as if he was chasing her as he twisted and turned while she pretended to flee. Diane dipped her chin coyly at the conclusion, the dancers ending together. It was an enchanting performance and the guests were enthralled, especially my family. Mama beamed like a proud bird that strut her finest feathers. In this case the feathers were her family and the culture that had formed them. The dancers twirled past her in a blur of color and light that seemed to intensify with each flurry of the Rondalla chords. I am sure many of the villagers had not seen anything like this since leaving their homeland as children and teenagers, so many had beaming smiles and tears in their eyes.

The Money Dance was eagerly awaited because it gave the guests a chance to bless the new couple and wish them good fortune. During the dance, giggling women and men placed coins as well as paper money in my mouth, everyone now a little tipsy. Children eagerly waited to be a part of the ritual as well. They would beg the parents for coins so that they could partake in the gaiety. Philip’s task was to take the money from me with a kiss. His hands had to remain behind him the entire time, as were mine behind me. We both leaned into each other as the music and gaiety intensified. There were hoots and hollers at each feigned kiss.

As we turned, came together, and drew apart in the dance, Philip snatched the coins and bills from my mouth with his teeth and then let them drop to the wooden floor. The light caught on the coins and sparkles of silver and gold flew in the room, making a ringing, jangling noise. (The dance came from the days of the Spaniards, so gold coins were a part of the custom.) As the spirit of this dance caught on, everyone jumped up enthusiastically with money in hand to give the new couple. At one point a line formed as people waited for us to dance into the corners of the hall. These days the custom continues but has been carefully sanitized! Small little plastic baggies hold the folded cash. I guess it makes sense but I remember sitting next to my sister-in- law Rosita, at a Molokai wedding in Kaunakakai many years later and said: “Not the same, ya? Ours was the best!” She smiled.

Before the Money Dance, my sister-in-law instructed me about the proper protocol required for this time. With wide eyes and serious consternation, she cautioned “Do not look at the money; when Philip takes it from you, he will let it drop to the floor, do not ever look at the money, even when it is on the floor. People will think you are greedy if you watch the money. They will think you are counting already.” It was emphasized my behavior on this day was critical to the success of the marriage as well. The message was clear; because all the people at the party knew Philip since childhood, all eyes would be on me.

My mother managed to thwart one tradition. Once we left the party, Philip and I were supposed to stay in a small house for seven days after the wedding. All of our meals would have been left at the door, as we were not supposed to leave the wedding house, an ancient tradition to yet again assure the success of the new couple. My mother, however, purchased a honeymoon for us in Kona on the Big Island of Hawai‘i. She slipped us away with some story to the airport after we left the party. The celebration continued anyway. I am not sure we were even missed.

We heard that the feast that followed the wedding went on for three days. In the midst of all the preparations I don’t think I stopped to think where all the food had come from. It was truly a blur of flowers and a mix of aromas that blended to a sweet memory for all time.

With the proceeds from the money dance, the gift envelopes, and the shot table bowl, we had about a thousand dollars (we thought we were very rich) tucked into a brown paper lunch sack. We arrived in Kona on a Sunday when all the banks were closed, so we hid the money under our bed in the sack, now very creased from my clutching.

We were officially married and beginning our lives together.