In plantation lingo, the end of the work day. But for the 675 employees of Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Company (HC&S), Alexander & Baldwin’s announcement on January 6, 2016 that it was shutting down its Pu‘unënë mill and farm operations by the end of 2016—the closure of the last remaining sugar plantation in Hawai‘i—pau hana meant the end of their jobs and an uncertain future.

For Maui and the rest of the state of Hawai‘i, the closure of HC&S marked the end of King Sugar and an end to the plantation era. For much of the 19th and 20th Centuries, Hawai‘i plantations dominated the islands. To support the labor needs of the sugar and pineapple fields, the plantations over eight decades brought thousands of contract farm workers from China, Japan, Portugal, Puerto Rico, Korea, and the Philippines. In time, those immigrants and their descendants came to make Hawai‘i their home and developed a lifestyle out of plantation paternalism that allowed these workers, including Filipinos to own their own homes in Dream City and elsewhere. Plantation wages—hard won through union actions and earned in the fields and factories, would also allow those same workers to send their children to college. For the Filipinos, the last of the larger groups of contract workers brought to Hawai‘i, plantation work allowed many Filipinos to support their families back in the Philippines. It also allowed many Filipinos to bring their family members to Hawai‘i to start a new life.

Ironically, December 20, 2016 marked the 110th anniversary of the arrival of the first Sakadas but in deference to the plight of the 675 HC&S employees, local Filipino community groups planned no grand celebration.

This Tournahauler, driven by Fermin Domingo, hauled the last load of sugar cane to the mill.

Photo courtesy: Michael Ross

“I was shocked. I had student loans over $40,000 so I had to start looking for another job,” said Roman Valle, 22 of Wailuku. He joined HC&S in May 2014 as an Internal Combustion Engine Apprentice after graduating from Baldwin HS in 2012 and receiving a Diploma in Automotive Light Duty Diesel from Wyotech in Sacramento.

Like many other HC&S workers, Roman’s family’s roots in HC&S go way back. Roman’s paternal great grandfather, Emiliano Valle, worked at HC&S. And Roman’s maternal grandfather, Jose Delos Santos, also worked at HC&S.

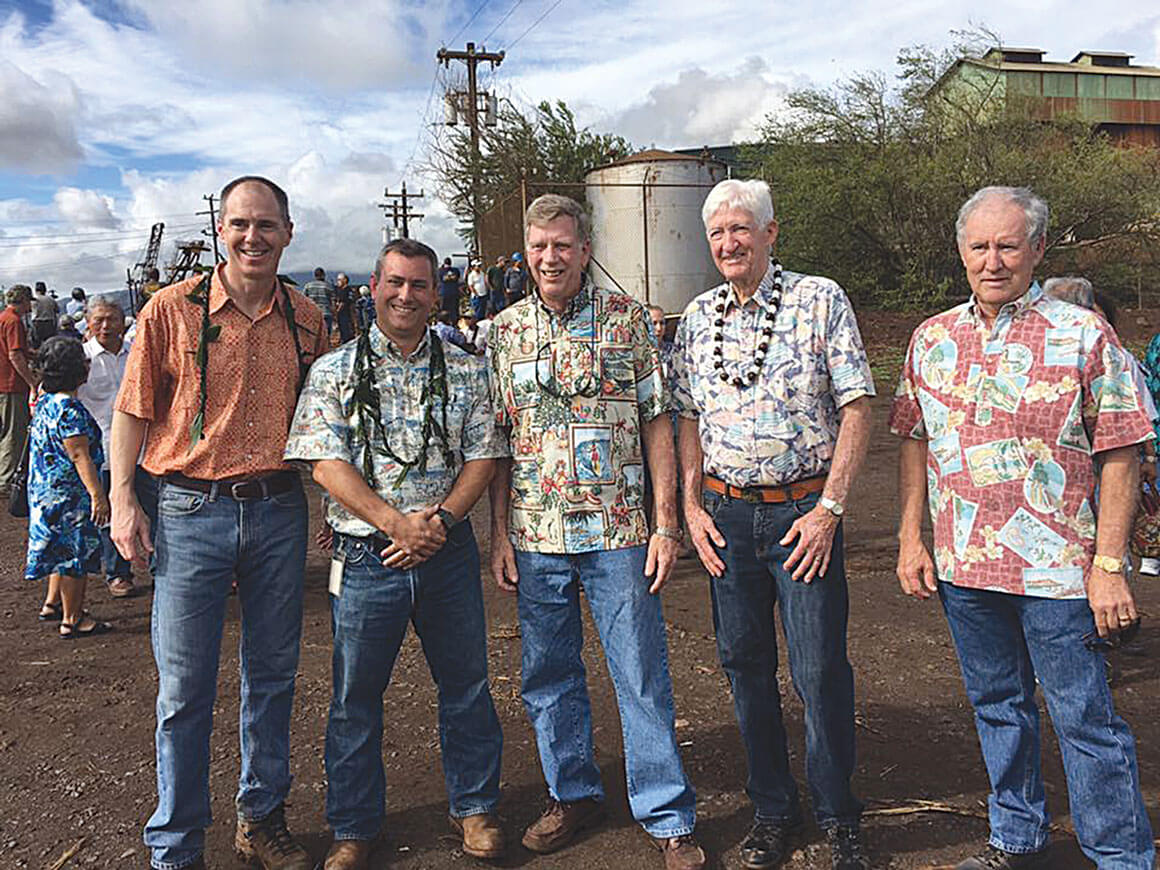

HC&S Farm Managers: (L-R) Chris Benjamin, Rick Volner, Jr., Frank Kiger, RIchard Cameron and Steve Holaday.

PHOTO COURTESY: GIL KEITH-AGARAN

In Roman’s department, there were about thirty mechanics; half of them employed at HC&S for over ten years. Most of them were laid off throughout 2016. Roman knew the numbers and knew the scarcity of jobs so he left in March 2016—giving up all his transition benefits and found a job as a field power generation technician with a Maui company. Three months later, Roman became a Field Equipment Mechanic at Bacon Universal in Wailuku.

Roman’s dad, Roland Valle, decided to stay till the end.

[row]

[column md=”6″]

On December 12, the end became real when the last Tournahauler, driven by Fermin Domingo, brought the last load of sugar cane to be processed. Roland, and the 370 remaining HC&S employees, together with former employees, retirees including 1946 Sakada Silvestre Baggao, and government and ILWU officials, were on hand to witness the last haul. Baggao, now 89 years old, quietly absorbed all the festivities and was interviewed by the television stations. Baggao was happy the retirees were being recognized but sad knowing the mill was closing.

For the rest of December, the feeling of sadness continued. Two days before Christmas, the Pu‘unënë mill stopped its operations. And a day before the end of 2016, 350 employees were laid off.

Roland, 45 years old, will receive a much needed severance package as his wife is a student at the University of Hawai‘i Maui College and he has a daughter in high school and a daughter in grade school. The closing of a mill is not new to Roland as he began as a Millwright (mechanic, welder, machinist) at Pä‘ia Mill and moved to Pu‘unënë when the Pä‘ia Mill shut down in 2000. Roland became an electrician and eventually became the Power Plant Electrical Supervisor. Fortunately, Roland has a job lined up in the hotel industry in the same field but is still worried about providing for his young family.

[/column]

[column md=”6″]

1946 Sakada Silvestre Baggao, now 89 years old, was interviewed by the television stations.

Photo courtesy: Myrna Baggao Breen

[/column]

[/row]

Steve Castro, the Maui Division Director of the International Longshoremen and Warehouse Union (ILWU), estimates that as of press time, twenty-five percent of his union members were able to find replacement jobs. 2016 was not a great year for ILWU as the Mäkena Beach and Golf Resort announced on March 29 that it was closing on July 1, laying off some 350 workers. “This year has been a year of uncertainty with the closure of HC&S and Mäkena Beach,” said Castro. “It’s been devastating for these workers. Some of those losing their jobs are husband, wife, and children in the same household.”

ILWU has been doing everything it can to assist its members. “Working together with HC&S, we were able to obtain our union members additional benefits,” Castro said. “The effects bargaining team, led by ILWU president Donna Domingo and the ILWU negotiating committee, were able to secure additional benefits such as two additional days of severance pay for a total of eleven days. Plus the union secured seven months of additional medical coverage.”

Governor David Ige used the ILWU union hall in Wailuku on June 17 to sign into law certain bills that would assist displaced HC&S and Mäkena Beach and Golf Resort workers. Normally, unemployment benefits last twenty-six weeks but the law added thirteen more weeks. Governor Ige also signed another law which provided funds to assist job training of displaced workers.

Displaced HC&S workers are also eligible for Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA), which provides federal funds to workers who lost their jobs due to foreign trade, as announced by United States Sen. Brian Schatz in March. While each displaced worker’s benefits will be different, the types of benefits include training, income support, job search and relocation allowances, wage subsidies, employment and case management services, and health coverage tax credits. To access their TAA benefits, HC&S employees need to contact the Workforce Development Division One-Stop Office at 2064 Wells Street, Suite 108 in Wailuku (telephone 984-2091).

Despite the closures shrinking his union membership from some 6,000 members to about 5,200, Castro emphasized the focus should be on the workers. “I’m proud of the ILWU team led by Donna Domingo,” said Castro “and most proud of our union members for their hard work and dedication. The working people of Maui has changed our community and HC&S workers have historically come from a diverse workforce and they all contributed to Maui County.”

While Castro’s main focus is on the workers, many speculate on what will replace sugar on Alexander & Baldwin’s 36,000 acres.

Rick Volner, HC&S General Manager, has mentioned efforts to transition some acreage to pasture to provide more ranch lands to raise local beef, and continuing efforts to identify biofuel crops. He asserts that A&B envisions many smaller farms growing a variety of crops but identifying specific plantings and the farmers to work the land has been slow.

The continued and future use of the 36,000 acres will also depend on the availability of water. HC&S relied on ditch water diverted and transported from East Maui streams for its Central Maui farmlands. Some lands both owned and leased in the Pu‘unënë and Waikapü area were fed by waters delivered through the ditch system created by the privately owned Wailuku Water Company, that was created after Wailuku Sugar and Wailuku Agribusiness Co. closed.

On December 12, the smokestack was still blowing smoke but a few days later all smoke stopped.

PHOTO COURTESY: KARI LUNA NUNOKAWA

In mid-December, the state Board of Land & Natural Resources extended revocable permits for East Maui Irrigation, a subsidiary of Alexander & Baldwin, to continue to divert water from East Maui streams where the diversions are located on public lands. The Land Board, however, capped the diversion quantity at 80 million gallons per day, down from 160 million gallons per day, and placed other conditions on East Maui Irrigation. In addition, the 2016 legislation that allowed the Land Board to even consider an extension limited the number of annual extensions.

For the Pu‘unënë and Waikapü sugar lands, the State Commission on Water Resource Management (the Commission) has been holding a contested case hearing to determine water use allocation for various existing and new user applicants, including HC&S, kuleana owners and others, and to determine whether any of those applicants are entitled to appurtenant water rights. Further complicating the water situation, recently the administration of Maui County Mayor Alan Arakawa announced it would be pursuing the purchase of Wailuku Water Company’s diversion and delivery system and some of its watershed holdings for $9.5 million. Whether the Wailuku Water Company diversion and ditch system is operated by the County of Maui—which relies on the ditch system for a good portion of the potable water for its residents, and pays Wailuku Water $250,000 a year—or remains in private hands, the Commission ruling will determine how much water is returned to the Nä Wai ‘Ehä streams, and which users are entitled to water allocations.

While there are many issues yet to be resolved, a lawsuit against HC&S brought by three Maui residents to stop the cane burning was settled. This divisive issue spilled over onto social media after some involved in the cane burning issue said they were going to do a “happy dance” after HC&S announced its closure. In this day and age of instant news on the internet, concerns have been raised about the proliferation of rats, dust plumes, and whether Alexander & Baldwin would try to develop the lands zoned agricultural. But Alexander & Baldwin designated approximately two-thirds (27,294) of its acreage as “Important Agricultural Lands” which under State law places greater restrictions with regard to changing land use designations or zoning.

Beyond the HC&S jobs, the land, water, and the environment, HC&S’ closure also impacts the local community that worked with HC&S. For example, businesses such as Maui Chemical and Paper Products depended on HC&S for their own sales. Further, HC&S was a training ground for many trades which augmented or substituted for more formal apprenticeship programs. For example, Maui Electric would routinely hire electricians that apprenticed with HC&S.

Although the proverbial writing was on the wall for the eventual closure of HC&S, this final year of sugar still provided a shock to many that the plantation way of life was finally ending. Many took to social media to simply express their sadness and memories, or in some cases, optimism about the opportunities that may come, or to simply celebrate the end of a polluting, paternalistic and anachronistic business structure.

Maui’s Filipino community faces multiple challenges. It’s a community built on the sacrifices of the Sakada pioneers in the sugar and pineapple industries, farm workers that took a risk to come to Hawai‘i for a better life for their families. But it’s also a community with a significant portion already disconnected from plantation life.

Since the creation of planned communities like Dream City and the closure of the camps, Maui has been transitioning to a post-agricultural society. Pineapple downsized and then almost completely ended—as it did on Molokai and Läna‘i—in the last twenty years. Drought and processing challenges have been problematic for local cattle ranchers. The effort to modernize and re-purpose the Kahului Cannery did not pencil out and so passed the opportunity for a summer job to save money for college.

Sugar, of the large-scale agribusinesses, held out the longest on Maui thanks to the largely contiguous nature of the HC&S acreage, but it is now gone together with the hundreds of jobs and opportunities it provided.

Some have called the tourist industry as the next plantation—providing hundreds of jobs for Maui residents—but the closure of the Mäkena Beach Resort and the conversion of other hotel rooms, is a reminder that nothing is set in stone.

The other remaining leg of Maui’s economy is construction which provides another substantial source of training and jobs for various trades but when the economy goes down due to forces not within the control of Hawai‘i businesses or the government, construction slows. Maui also does not have the same amount of military investment as O‘ahu, Kaua‘i and Hawai‘i Island or the facilities that bring military personnel into the community and economy.

The Sakadas advised their children and grandchildren to go to school and study hard to avoid the back breaking work they did. Many Sakada offspring took their advice to heart… and many youngsters will continue to follow a career path towards science and technology. But the somber reality is Maui in the near term does not and probably will not offer them working opportunities to use their educational success at home. The Maui Research & Technology Park simply cannot provide the volume of jobs that the sugar and pineapple industries provided. What industry will provide jobs so the people of Maui will be able to afford to buy their own homes, send their kids to school, and yes, contribute to the well-being of the community?

No one can sugarcoat the impacts of the HC&S closure on Maui’s community. Residents, businesses and government will indeed be affected by the last pau hana.

Gilbert Keith-Agaran contributed to this article.