A Cayetano Retrospective: The 1998 Election

Benjamin Cayetano: First highest-ranking elected official of Filipino ancestry in the State of Hawai‘i: 11th in a series.

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran

Editor’s Note: 2019 marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the election of Benjamin J. Cayetano as the Fifth Governor of the State of Hawai‘i and the first Filipino-American elected as the head of an American state. This is the eleventh in a series of articles profiling Cayetano and his historic election and service. Versions of these articles appeared previously in The Filipino Summit.

In the final week of the 1998 General Election, time slots for coveted television ads suddenly opened up. The rumor was that the Cayetano-Hirono team appeared on the way to the first defeat of an incumbent Governor since Bill Quinn lost to Jack Burns. A media poll showing the favorable-unfavorable ratings of Governor Cayetano and his opponents suggested a large lead for Linda Lingle. Lingle’s internal poll, from a mainland consultant, indicated she led by 10+%. The Lingle campaign was so confident that some visited the Governor’s public reception to see where they would sit when they got their political appointments. Hearing about the visit, Governor Cayetano told the staff that if they returned, they were free to go into his private office to measure the curtains. Whatever the thinking, the Republican campaign apparently had cancelled their reserved ad buys. But the internal polling for the Governor suggested some undecided shifting and a virtual draw. For the campaign strategists, the availability of commercial slots was an opportunity, provided the fundraisers could find the money.

Image courtesy Alfredo Evangelista

The Primary results in September foreshadowed the tough General election campaign. The GOP candidate, term-limited Maui Mayor Linda Lingle, out-polled Governor Cayetano statewide 109,399–96,019. In fact, Lingle had more votes on the two most populous islands—O‘ahu by 21,286 votes and Hawai‘i by 631 votes. GOP Primary Candidate Frank Fasi drew 41,397 votes on O‘ahu to Cayetano’s 59,608 and Lingle’s 80,894. Kaua‘i provided the only clear advantage for Cayetano who collected 4,261 votes more than Lingle on the Garden Island.

Surprising the academic and media pundits who assumed Maui County would support their Mayor, Valley Islanders favored Cayetano by 4,445 votes (14,635–10,190 with Fasi drawing 2,390 votes). One Maui wag quipped that’s because we know her the best. For Cayetano, that also pointed out that perhaps the rest of the state just didn’t know her well enough.

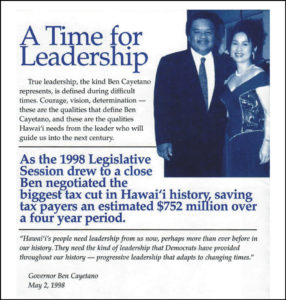

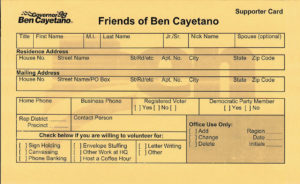

Of course, the campaign ground troops tried to get its message out in traditional ways as well—brochures that touted the accomplishments and what some of the younger campaign veterans referred to as “that vision thing.”

And there was a pretty good story to recount.

Image courtesy Alfredo Evangelista

Also, the Hawai‘i Home Lands department built or was building nearly 3,100 residential homestead lots and homes—exceeding the 3,000 built by the department in the 74 years before Governor Cayetano took office. He could rightly say, “in the three-and-a-half years of my administration, we have been able to open up more homestead lots to Native Hawaiian families than any administration in State history.”

The incumbent also pointed to the new direction for the business climate—where “the State would become a facilitator rather than a regulator of business.” He pointed to the one-stop new business form which replaced two dozen forms that new enterprises had been required to complete. Out of the ERTF process, supporters also pointed to the new mandatory approval law which set deadlines and timeframes for processing licenses, permits and other government approvals. Further, he could note the reduction in workers compensation rates which at 37.5% was the largest in the nation.

The hallmark of his argument was the biggest cut in state income taxes—only ten other states had made larger reductions in the previous five years. The top rate reduced from 10% to 8.75% and over the course of four years would end up at 8.25%. For Hawai‘i’s middle class, a family of four filing a joint return would see their tax rate fall from 10% to 8.25% in the first year and 7.6% in the fourth year of the new law. The administration projected the tax cuts to save taxpayers $750 million over four years. As Cayetano said to supporters at a rally on June 23, “That’s money back in your pockets, starting the first day of 1999.”

Image courtesy Alfredo Evangelista

Cayetano also touted the traditional priming of the economy with public works. The construction industry, which had lost nearly 12,000 jobs since 1991, received a boost from Cayetano’s $1 billion capital improvement program. More than half the appropriations went for construction of new schools, classrooms, libraries and other educational facilities. That allowed the administration to be on pace to set a record for a four-year administration in building 11 new schools and 900 new classrooms. As Cayetano boasted at the June 23 event, “We put people back to work and helped education in Hawai‘i at the same time.”

In addition, the administration pushed $1.3 billion more in transportation capital improvement projects.

Cayetano chaffed at the usual GOP talking point about cutting government. Cayetano argued that in his first term, he had worked hard at streamlining state government—reducing growth from 8% to 1.6% and eliminating 3,000 full-time positions. The talking point was that Hawai‘i government “spends less in state expenditures than it did when Governor Cayetano took office in December 1994.” He told supporters, “Our opponents talk about cutting government as if it would solve all our problems. These kinds of easy answers are okay for candidates who have never had to take responsibility for their words. But this year the voters will judge by a higher standard. A tougher standard. They’ll demand the truth from candidates. That’s why I welcome the campaign ahead, because we’re not afraid to point to the record.”

Image courtesy Alfredo Evangelista

In his autobiography, Cayetano recalls early polls showed his approval ratings declining while his possible opponents Honolulu Mayor Jeremy Harris and Maui Major Linda Lingle rising. He honestly writes, “[w]hen pressed by the news media for comment I gave the usual responses: ‘The only poll that counts is on Election Day,’ ‘This is not a popularity contest’ and so on. Actually, I was very disappointed. Any politician who claims he doesn’t care what the public thinks of him is being disingenuous.”

The bravado at the June rally did not easily translate to changes to the polling. A few weeks before the June 23 event, an internal memorandum regarding expanding Cayetano’s Filipino support observed, “At the moment, BJC trails badly and needs to secure groups with a greater history of loyalty and influence in Democratic Party election successes.” An internal poll showed Lingle leading by 22% in June. Although Cayetano led among AJAs and Filipinos, he trailed Lingle narrowly for union members.

For the campaign’s analysts, the September Primary results highlighted the shortcomings and suggested even a weakness from another key voting bloc. The most telling discrepancy in the Primary for the gurus was that Cayetano failed to keep pace with Hawai‘i’s Senior U.S. Senator Dan Inouye. Statewide, Inouye out-polled Cayetano by 13,109. On Maui, 2,514 Inouye voters did not cast a ballot for Cayetano. On Kaua‘i, another 1,064 DKI voters opted not to cast a Cayetano ballot. Big Islanders cast 2,949 more votes for Dan than Ben. Honolulu included 6,582 Inouye voters more than Cayetano’s total.

Image courtesy Alfredo Evangelista

Inouye’s votes provided demographic shorthand for the campaign braintrust for key voters in the Democratic Party of Hawai‘i base—Americans of Japanese Ancestry (“AJAs”). Since the 1954 Democratic Party Revolution, AJAs had been their most reliable voters along with union members. In the years since Statehood as more AJAs were able to access jobs in the State bureaucracy, AJA votes also meant public worker union votes. The numbers were sobering for Cayetano and his campaign advisors given his long elective history representing AJA communities in the State House and State Senate.

Cayetano had also observed as he campaigned that the AJA and union base of the party was graying. He noted, “Democrats were victims of their own success. For many, the struggle for social and political equality had opened the doors to better lives. Democratic parents were able to provide their children with better education, greater economic opportunities and expanded social mobility. But there was a political price to pay.” In his autobiography, Cayetano wryly quotes a union leader’s lament, “We Democrats have been so successful that we spoil our kids, give them everything we never had; they don’t know what it means to sacrifice, and now we’ve created a bunch of Republicans.”

Twelve years earlier in the hard-fought first campaign for Lt. Governor, Cayetano had displayed his political instincts when he jumped to support the AJA community against what some perceived as a veiled slur by a fellow Filipino politician against Hawai‘i’s important Japanese voting bloc. In a tough race as an underdog to the former Honolulu Mayor, Cayetano emerged as the Democratic nominee. That victory paired with Cayetano with John Waihe‘e who upset the favored U.S. Congressman Cec Heftel. Ironically, the pundits thought the more balanced tickets would have been Heftel-Cayetano or Waihe‘e-Anderson but the voters thought otherwise.

In Catch a Wave, Tom Coffman chronicled one of the first modern campaigns—a Governor’s campaign in Hawai‘i built as much on polling and media as on the traditional bread and butter of boots on the ground knocking on doors and passing out flyers and holding grassroots speeches and rallies. While union endorsements and the volunteers and money that came with them still played a role in showing support, mass media had become accepted as the most efficient and effective way to reach the largest number of voters.

Candidates themselves could still make a difference, of course, but mainly in their mistakes.

In one of the last televised debates between the two gubernatorial candidates, the incumbent impatiently waited for the right moment. In debate prep, they had practiced some barbs but insisted he should use them sparingly. But they also knew Cayetano wouldn’t wait very long because the Maui Mayor brought a well-earned reputation for articulate, poll-vetted responses and wouldn’t be caught off-guard. At some point, he pounced, describing one of her responses as resembling a Texas longhorn—a point here, a point there, a whole of lot of bull in the middle.

Somehow the fundraisers were able to convince enough donors to contribute and the campaign bought much of the freed time. As the internal polls tightened up, the GOP found television time was now severely limited as Cayetano-Hirono ads that pointed out the accomplishments of the first term filled the airwaves. With the message questioning what Lingle had actually accomplished and reminding voters she was still a Republican in the mold of Newt Gingrich, Cayetano won a close victory.

In 1994, the Maui campaign started celebrating after the first print out which showed Cayetano ahead on O‘ahu—in their calculation, his strength was in the neighbor islands and he would likely win.

In 1998, Cayetano led after each print out but had to survive the late reporting of the heavily Republican Kona precincts that cut his 12,000-vote lead to the final margin of 5,253.

Cayetano avoided being the first incumbent Democratic Governor to not win a second term.

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran served in the Cayetano Administration. He presently is the State Senator from Central Maui.

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran served in the Cayetano Administration. He presently is the State Senator from Central Maui.