Heroes, Revolutionaries and Settlers

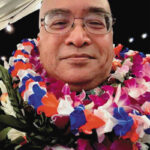

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran | Photos courtesy Gil Keith-Agaran

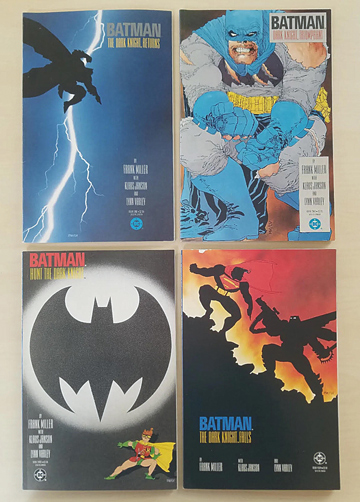

I am not loving Chip Zdarsky’s Batman run. Frank Miller’s dark, dour, older world-weary Dark Knight is my guy. Do not get me wrong, I appreciate the cinematic storytelling quality of Jeph Loeb and Jim Lee’s Hush pieces and Loeb and Tim Sale’s young Batman Holiday crime saga. I suppose my reaction to the various incarnations of the Caped Crusader colors how I view “heroes.”

I imagine many Filipino diaspora communities annually mark the end of the year by remembering Dr. Jose Rizal, the national hero of the Philippines. Maui community leaders installed a bust of Rizal at the Filipino section of Kepaniwai Park’s heritage area decades ago. The Maui Filipino Community Council usually holds a gathering near the anniversary of his execution by the Spanish authorities on December 30th.

Rizal is often described as a renaissance man, a poet and novelist, and a tragic figure of lost unrequited love. Perhaps something got lost in translation but I could not get through his famous novel Noli Me Tángere.

Suffice to say while I appreciate the myth constructed around the educated scion of the Filipino native aristocracy as a symbol of popular resistance to Spanish colonial restrictions—I have always been drawn to the rougher figures in the Philippine revolution. Frank Miller could do more with the likes of Andres Bonifacio and Emilio Aguinaldo.

The uneducated Bonifacio founded the nationalist Katipunan society. While Rizal supported reforms, Bonifacio wanted full independence and sparked the August 1896 revolt against the Spaniards. Ironically, the Spanish authorities arrested reform advocate Rizal. They argued Rizal’s writings inspired the revolution. The colonial government eventually shot Rizal by firing squad.

Of course, my preference for the warriors recognizes neither Bonifacio nor Aguinaldo were the William Wallaces of the Philippines. No one argues Bonifacio was a very successful military leader—no Stirling Bridge for him. Eventually Aguinaldo, one of his underlings, would have Bonifacio arrested and executed.

With the United States of America taking on Spain, Aguinaldo and other Filipino rebels thought independence was within reach. While the Americans debated annexation of Spanish territories seized during the Spanish-American War, the Filipino rebels declared independence and Aguinaldo was declared the first President of the Philippine Republic. The American authorities, however, decided their little brown brothers required and deserved some good old fashioned Yankee guidance. It was the Americans who introduced the concept of martial law to the archipelago. Aguinaldo and the Filipino rebels would fight the Americans.

They lost.

Aguinaldo would swear an oath of allegiance to the United States, retiring to private life with a U.S. government pension.

He would later return to public service by collaborating with the Japanese occupation during World War II. While arrested after the American victory for his wartime activities, he was not shot. After independence, Philippine President Elpidio Quirino would appoint him to the Council of State and Aguinaldo reputedly would work for better Filipino-American ties.

In college, during a seminar on Modern Southeast Asian History, we had a lively debate on whether the martyred Rizal simply made a more palatable national “hero” to both the new Yankee colonial overlords and the local oligarchy that would run the American commonwealth. The failed nationalists Bonifacio and Aguinaldo did not fit into the narrative of a more benevolent American empire.

But I still think Aguinaldo’s saga would make a better graphic novel.

I hail from the tail-end of Maui’s sugar era. Plantation days weren’t all reservoir swimming and tilapia fishing or tournahauler inner tubes as local kid trampolines. My parents went to bed early and awoke before dawn (my mom still does). Red HC&S pickups would fetch the hanawai gang from our Kahului neighborhoods for the drive to the assigned fields. My heroes did not wear palaka. They wore dusty cotton work shirts and floppy hats to shield them from the hot sun in the fields. Just looking at my dad when he came home, I had no doubt he led a hard, dusty life—but there was also dignity in his face and the face of his co-workers. It was also a life that some in my generation chose for themselves, following in their parents’ and grandparents’ footsteps. But I understand why my dad and other sugar workers wanted their children to have other choices about our futures.

The Agaran Sakadas came to Hawai‘i when sugar still ruled. Lino and his cousin Teodor (“Doro”) arrived on Maui on April 5, 1928 while brother Juan (“Uncle Johnny”) landed on Hawai‘i island in November 1929. Uncle Toribio came earlier to either Kaua‘i or Lāna‘i. The dates and places differ depending on which of the cousins tells the story. All four are gone now. In our family folklore, my dad Manuel Coloma arrives in 1946, recruited as an Ilocano strikebreaker. As remembered, he signed an ILWU card on the boat, joining strikers upon disembarking at the port. That strike won; dad worked the Maui sugar fields spreading out from Pā‘ia town’s edge as an irrigator for nearly forty years.

A proverbial Ilocano—a stoic, frugal, careful man—he married Lydia Agaran, a woman from his old ili. A soft-spoken father, he stepped in only when my exasperated mother was pau with my sister Velma or me. We lived at various camps but the clean, plain cabin in Orpheum Camp near Pā‘ia Mill stands out most in my memory, even more than the little tract house they purchased in Kahului’s Twelfth Increment in the early ’70s

.

After the war, my Papa Lino moved to O‘ahu. He adopted and raised me. When he retired in 1967, my grandmother, Papa and I moved back to Pā‘ia. In those days, there were no Filipino caterers, so Papa was invited to parties because he could cook for large groups. He fried pork chunks dipped in flour and scrambled eggs with a sweet-sour sauce for dipping, pancit the Ilocano way, a dry but tasty dinardaraan, pork and peas or pimentos, pork adobo, lightly fried chicken and chicken long rice.

At gatherings at the Pā‘ia Club or Pu‘unēnē Filipino Club House or the Baldwin Park pavilions, he would launch into those formal Filipino tarantellas inspired by some kind of Spanish flamenco. In my child’s eye, I still picture the steps and the arm movements as he swirled across the floor with various partners.

Throughout my life, Maui’s countryside shifted away from sugar (and pineapple). Family-owned independent pineapple fields and pastures in Ha‘ikū subdivided into two-acre Gentlemen farms. That familiar experience where you and your high school pals would spend summer months making some real money at the Cannery or in the fields is no longer common. At one time, Pā‘ia and Pu‘unēnē—with their smoking sugar factories—were among Maui’s largest company towns.

But while I was away at college, Pu‘unēnē town disappeared into Central Maui sugar fields and big box parking lots. In 1999, Lahaina’s Pioneer Mill shut down like the rest of Amfac’s agricultural operations throughout the islands, and Maui Land & Pineapple ended active pineapple operations. Pā‘ia converted to windsurfing hostels and vacation rentals, fashion shops, Mana Foods and quaint eateries. Pā‘ia Mill stands dead on Baldwin Avenue. The camps are largely gone or redeveloped. South Maui and West Maui Beaches we frequented and camped on small kid time are now blocked off by hotels and condos. And in 2016, Pu‘unēnē Mill closed and HC&S ended sugar cultivation.

I am old enough to recognize Filipinos and the Filipino community throughout my life sometimes seem outside the mainstream. Our role remains perhaps as cheap labor for the Visitor Industry’s back of the house just as the Sakada generation provided the field workforce for the plantations, or filling food and other service jobs that aren’t viewed as living wage careers.

I guess American pop culture shapes my attitude. But I will attend the annual Rizal Day event if one is held. In the aftermath of the August 8th fire that destroyed Lahaina and killed nearly a hundred local residents, any holiday celebration will be colored by that event.

I have said Filipinos have a reputation as a very optimistic people. Filipinos are a resilient people, full of hope and full of laughter even in the face of adversity. One travel book actually states even though there are over seventy major dialects spoken in the Philippines, not one of those dialects includes words for “depression” or “anxiety” or “anguish” or “boredom.” It is an exaggeration but Filipinos do try to see the silver linings in every cloud that comes by in our lives.

This fire is a big test of that lore.

Many local Filipinos can trace our family lines to grandparents or great grandparents who were Sakadas. After the immigration reforms of the 1960s, more kababayan have come to Hawai‘i as part of family reunification but without direct connection with the jobs that drew the farm laborers who helped build modern Hawai‘i. The Lahaina community of Filipinos reflected a mixture of retired plantation laborers, visitor industry and health care workers, teachers, small business owners and professionals.

While a Rizal Day event remembers our roots, this year should celebrate the beauty of our people, commemorate what we have now, and share our culture with our neighbors in Hawai‘i.

At what point are Filipinos not just derisively described as settlors but recognized as equal and permanent residents of this community? Is hula a talent in a scholarship pageant but perhaps a Visayan folk dance is not as valued? And does that unspoken question about the alien-ness underlie an uncomfortable suspicion some will view Filipinos as akin to tourists here no matter how many generations have been born and died here—like the suggestion on social media during the pandemic that if the hotels, like the plantations, fade away, so will the Filipinos, who can just go back to the Philippines.

Filipinos, especially immigrants, are not easily integrated into the local community completely. Newcomer children may not be on youth soccer or baseball teams with parents too busy in their jobs to attend games anyway. They may not participate in extracurriculars unless recruited by friends or a teacher. Even as Filipino children make up growing numbers in our public-school student bodies, Filipino teachers have not kept up.

A paucity of role models remains true in most workplaces. Tons of Filipino workers but few managers, or executives. You see more Pinoy nurses than doctors. There remain few kababayan examples in established businesses, financial institutions, law firms or academia. Admittedly, quite a number of local leaders might be part-Filipino but have outlooks reflecting their mixed-heritage in relating to the diaspora community. As a local-born Filipino, I plead guilty I lean decidedly American even though I am Full-Blooded Ilocano (FBI).

Filipinos sometimes act like we are just visiting these islands. It’s a stop before moving on to Las Vegas or California or the Pacific Northwest for other opportunities. We, as Filipinos, have been strangers in Hawai‘i.

But for generations of us now, it has become home. But Filipinos are often missing in action when it comes to making their voices heard on the important challenges facing our community. Given the significant impacts the fires had on the Filipino community—few of us have no connection to a victim or survivor of that tragedy or the certain transformation happening all around us—I would suggest we should not be afraid of making our voices and concerns heard.

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran practices law in Wailuku. He worked under the first Governor of Filipino ancestry in the United States, Benjamin J. Cayetano (D-Hawai‘i), for eight years. He later served in the Hawai‘i State House of Representatives for four years and the Hawai‘i State Senate for eleven years.

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran practices law in Wailuku. He worked under the first Governor of Filipino ancestry in the United States, Benjamin J. Cayetano (D-Hawai‘i), for eight years. He later served in the Hawai‘i State House of Representatives for four years and the Hawai‘i State Senate for eleven years.