Caregiving for our aging population.

Alfredo G. Evangelista | Assistant Editor

Photo: Alfredo Evangelista

Maui’s growing aging population increasingly impacts lifestyle and healthcare options over generations. While multi-generational households persist for many reasons, the challenges posed by senior caregiving are requiring families to make some difficult choices.

Eighteen years ago, my gravely ill father Elias bounced back and forth between Maui Memorial Medical Center (MMMC) and home. After a lengthy stay at MMMC, my eighty-one-year-old dad briefly transferred to Hale Makua in Wailuku until he could regain his strength to return home. The transition also provided time for my mother Catalina to be trained as his caregiver and to ensure our house could accommodate my Dad’s needs.

My then seventy-five-year-old Mom needed some assistance so she hired a home health care nurse. My Dad’s Kaiser medical plan as an ILWU retiree did not cover those costs so she paid out-of-pocket for the help. Other family members like my niece Lydia Torres, a Certified Nurse Assistant (CNA), pitched in to help.

At the time, I was still living in Honolulu and practically useless and perhaps not wanting to face the reality that my Dad’s time was getting short.

We recently celebrated my Mom’s 94th birthday in Las Vegas. She had a great time but she’s not getting younger. My sister Gloria is now my Mom’s official caregiver while my other sister Estrelita provides temporary relief. My assignment is to bring Mom to church every Sunday because our car is easier for her to get in and out of. She’s slept twice at her Waikapū house where we live. However, our bathroom facilities are not accessible: she can’t utilize the shower because there’s a tub and it’s impossible for her to lift her legs over the rim and the shower does not have grab bars installed.

As our parents age, many residents face many tough decisions about their future care. In many cases, health care and living decisions are wrought with emotional and financial considerations. Sooner or later, however, families realize that time is short and they must decide whether they can care for their aging parent at home or they need to consider other options.

Hawai‘i, over time, has developed a continuum of choices for adult caregiving. Options for long-term care include Adult Residential Care Homes (ARCH), commonly known as “Care Homes”; Community Care Foster Family Homes (CCFFH), commonly known as “Adult Foster Homes”; and nursing homes that provide intermediate care facilities and/or skilled nursing facilities. Assisted living facilities such as Roselani Place on Maui are apartment communities for more independent adults while Day Care Centers such as the Maui Adult Day Care Center provide day time only programs.

Care Homes

Care Homes are licensed and regulated by the State of Hawai‘i Department of Health, Office of Health Care Assurance. There are basically two types of Care Homes—ARCH I and ARCH II. Briefly, ARCH I homes have one to five residents while ARCH II homes can have six or more residents. ARCH I and ARCH II homes can be regular or expanded. A regular home has residents who only need minimal assistance with their Activities of Daily Living (ADL) such as mobility, bathing, toileting, and eating. An expanded home is able to accept residents who need 24-hour assistance or skilled nursing services. Plus, only an Expanded ARCH I or ARCH II can accept Medicaid patients.

Confused already? Join the club.

Maui, as of July 2018, reports only ten licensed Care Homes: four in Kahului (all ARCH I), one in Kīhei (Expanded), and five in Wailuku (four ARCH I and one ARCH II—Care Homes by Hale Makua). The Department of Health maintains an online list of licensed care homes and vacancies. Visit health.hawaii.gov/ohca/files/2018/07/Combined-ARCH-Expanded-ARCH-Vacancy-Report-By-Area-7-2018.pdf. Based on the last names of the operators, except for the Hale Makua ARCH II which has 22 beds, all are owned/operated by Filipinos: Alipio, Dagdag, Della, Garcia, Ines, Jerez, Paranada, and Valdes.

Photo courtesy Judith Dagdag

“The residents are like my own family,” said Judith Dagdag, who has owned and operated her care home since July 1986. “I have one who’s been with me for seventeen, eighteen years. She came from a care home in Molokai. When she came to Maui, she was placed in another home and that care home operator couldn’t handle her because she is the wandering type. She came to me and I lost her about four times. Even though it was hard, I still didn’t give up on her. Sure enough, she’s stopped wandering now. She’s very helpful and she has a routine. First thing in the morning, she takes a bath, sweeps her room, and fixes her bed. She learned all those from me so now she’s okay.”

To be a care home operator has many challenges, according to Dagdag, who is a member of the O‘ahu-based Alliance of Residential Care Administrators (ARCA) to obtain her required insurance. “I cannot take vacations. I cannot go out unless one of my two substitute caregivers (my husband Fred and my son Frederick) is at home. Most of all, I must have patience.”

With that patience, comes many rewards. “The most rewarding experience involved a client who got married!” recalls Dagdag. “Another client went back to her family after about three to four years. Now she’s back with her family in Honolulu and she has a good life and is now working.”

Wanting to be with her family was actually the impetus for Dagdag to be a care home operator. “I had one year of nursing school at MCC but I got married and had kids. Luckily Dr. Chiaco hired me,” explained Dagdag. Dr. Jose Chiaco started as a plantation doctor with a Maui Clinic office but later moved his private practice to Pu‘uone Plaza. “I worked with Dr. Chiaco for eighteen years,” said Dagdag. “But when Rowena and Frederick were growing up, I wanted to be there. I wanted to be with them. I asked my husband if I could open a care home so I could be home when my kids came home.”

Over the thirty-two years of providing care, Dagdag estimates she has had over thirty residents. Even after the kids grew up, she continued with her care home. “I continued my care home because I didn’t know how to work anymore,” jokes Dagdag.

Adult Foster Homes

Adult Foster Homes are for residents at the Intermediate Care Facility (ICF) level of care or Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF) level of care, as certified by a physician. The Adult Foster Homes provide personal care, assistance with their ADL, homemaker services (meal preparation, laundry, shopping), room and board, and 24-hour services. Some Adult Foster Homes also provide recreational activities, transportation, and other services. Adult Foster Homes may have up to three Medicaid residents and one private pay resident. Adult Foster Homes are now licensed and regulated by the State of Hawai‘i Department of Health (they were previously under the jurisdiction of the State of Hawai‘i Department of Human Services).

Maui, as of January 23, 2018, lists 57 licensed Adult Foster Homes, with 37 in Kahului, 16 in Wailuku, and one each in Ha‘ikū, Kīhei, Makawao, and Pā‘ia. There is also one on Molokai. The Department of Health maintains an online registry of licensed Adult Foster Homes. Visit health.hawaii.gov/ohca/files/2018/01/Community-Care-Foster-Family-Homes-1-2018.pdf. Based on last names, at least 85-percent of the owner/operators are of Filipino ancestry.

Photo courtesy Roseminic Ulep

Roseminic Ulep, a licensed CNA, has owned her Adult Foster Home since August 2008. She was previously employed at Kula Hospital and Maui Memorial Hospital. “It wasn’t in my dreams to be in this field,” explained Ulep. “I wanted to go and work in a hotel. I applied but no one called me so I went to MCC for six months to get my CNA license. I started at Kula Hospital right after that.” But the recession would play a factor in her future role as a licensed caregiver. “During the recession, it was slow for everyone. My husband Chris got laid off from Dorvin Leis. At that time, we had a hard time paying our mortgage. I was a part-time personal care giver but it was still not enough. So, I decided to go into the Adult Foster Care home business.”

But it was not an easy task. “It was difficult to start because I didn’t know too many folks in the business as there were only about fifteen to twenty at that time. The application process was difficult. CommunityTies of America [Inc.] which was responsible for licensing the homes, did not come to Maui frequently. They would only come to Maui if there were enough homes to check. At that time, not too many folks were interested in opening an adult foster care home,” Ulep said.

Ulep is the current president of the Adult Foster Home Association (AFHA) Maui Chapter, which now has 62 members. Through AFHA, Adult Foster Home owners get their liability insurance, which is currently $440.00/year. In addition to maintaining insurance, owners are required to undergo annual continuing education—12 hours for those with three residents; eight hours for those with less than three residents.

Aside from the operational challenges, Ulep says her greatest challenge is dealing with behavioral residents–those with psychiatric problems. “You don’t know when they will have a tantrum,” Ulep explains. “My greatest reward is when they go see the doctor and they’re progressing with their health. The doctor will tell me ‘great job’ because the resident’s health is stable or has improved. For example, one of my residents used to need insulin but now is only on tablets, which is amazing.”

Perhaps the most difficult and confusing aspect of the Adult Foster Homes program is financially qualifying for Medicaid. The financial eligibility requirements change every year. For example, in 2018, residents are limited to an annual income of $18,567 or $1,547 per month—which is 133-percent of the federal poverty level in Hawai‘i. Plus the resident can have no more than $2,000 in countable assets (excluding their home). There are other requirements, planning techniques, and restrictions such as a five year look back period regarding the transfer of assets so one needs to consult with a knowledgeable professional to help the family through the Medicaid maze. Don’t rely on anecdotal experience. The State of Hawai‘i has a website that provides some guidance: mybenefits.hawaii.gov/medicaid-faqs/. Case Management Agencies, which coordinate the health care requirements of each resident, can also help applicants qualify for Medicaid. The Department of Health has contracted with CommunityTies of America, Inc. to certify and license the Case Management Agencies.

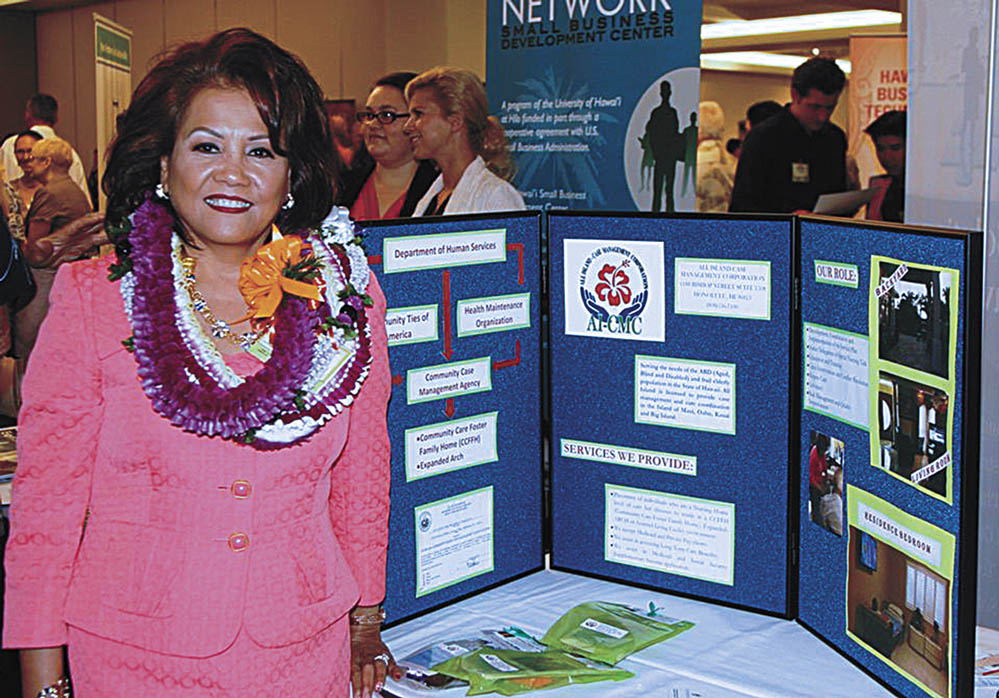

Photo: Alfredo Evangelista

Elsa P. Talavera, owner and president of All Island Case Management Company—one of the largest and leading case management companies in the State which has garnered many awards—explains the role of case management companies is to “coordinate the care of individuals who are at the nursing home level of care and place them in the community homes.” Talavera, who received her education from the Santa Teresita School of Nursing in Quezon City first became a Licensed Practical Nurse in 1982 and in 1983, passed her Registered Nurse exam. After twenty years as an RN at Kuakini and St. Francis, Talavera left St. Francis in 2002 during the nursing strikes and set up a case management agency.

Elsa P. Talavera, owner and president of All Island Case Management Company—one of the largest and leading case management companies in the State which has garnered many awards—explains the role of case management companies is to “coordinate the care of individuals who are at the nursing home level of care and place them in the community homes.” Talavera, who received her education from the Santa Teresita School of Nursing in Quezon City first became a Licensed Practical Nurse in 1982 and in 1983, passed her Registered Nurse exam. After twenty years as an RN at Kuakini and St. Francis, Talavera left St. Francis in 2002 during the nursing strikes and set up a case management agency.

“I get great satisfaction from my job which is to help find placement for the elderly,” says Talavera, who has clients on every island, with her main office in Honolulu and satellite offices on Maui and in Hilo. “We look for good homes, good caregivers. There’s a lot of people who you can help. A lot of the elderly do not have family to take care of them. These folks don’t have money; they can’t go to a nursing home because of the expense.”

Nursing Homes

The average cost for a nursing home is between $300 and $500 per day ($9,000 to $15,000 a month). Nursing homes—which are the traditional institutions versus in a family/home setting—are also licensed by the State of Hawai‘i Department of Health and provide ICF and SNF levels of care. Most nursing homes have Medicaid-eligible beds and may also have private pay beds.

On the island of Maui, nursing homes include Hale Makua Health Services in Kahului (254 beds), Hale Makua Health Services in Wailuku (90 beds), and Kula Hospital (105 beds). (Lāna‘i Community Hospital has 10 beds.)

“Adult Foster homes are saving the State of Hawai‘i a ton of money because the rate is so cheap compared to the nursing home facilities,” said Talavera. Ulep says the monthly cost for Level I residents (those who need minimal assistance as they can walk, feed themselves, and handle their own finances) is $2,500 for Medicaid clients while the monthly cost for Level II residents (those who need assistance to bathe, have continence problems, and cannot handle their finances) is $2,700 for Medicaid clients. Ulep says the private patient monthly cost ranges from $4,000 and up, depending on the level of care.

“There are about 2,500 residents in the community,” says Talavera. “The State is saving about $7,000 per month per client, which results in an annual savings of over $210 million to the State.”

Yet the State delays reimbursement to caregivers and case managers, according to Talavera, with the average delay being two to three months.

Delayed reimbursement is not the only government-related problem faced by licensed caregivers. Over the years, unlicensed care homes and unlicensed adult foster homes began operating. The operators would bypass the legal requirements of owning a care home by having the residents sign a rental agreement instead of an agreement to receive health services. State regulators would often be denied access to the illegal care homes and adult foster homes.

Photo courtesy Roseminic Ulep

The Legislature this year passed a bill (HB 1911) which Governor David Ige signed into law (Act 148) authorizing the Department of Health to investigate unlicensed care homes. Many of the associations representing existing operators such as ARCA and AFHA lobbied hard to ensure HB 1911 became law.

The value of organized efforts

Photo courtesy Mila Ka‘ahanui

The beginning of organized efforts for caregivers began in the late 1970s. In 1977, there were about two hundred care homes, with over 90-percent of them owned by Filipinos, including Mila Medallon. The first association of care home operators was the United Group of Home Operators (UGHO) founded by Medallon in 1977, with Eleanor Florendo as the first president.

“I founded UGHO because I got upset. The first time the state inspector came, unannounced, I was treated like a criminal. I told her to go to the public phone to call me and I slammed the door in her face,” recalled Medallon. The inspector did go to the public phone (there were no cell phones in 1977) and called Medallon, explaining an inspection of Medallon’s care home was needed.

“I thought to myself, wait a minute. Is this how care home operators are treated in the State? I called my good friend Eleanor and she confirmed that’s how we are treated. We gathered other care home operators for an initial meeting. There were 12 of us in that meeting, we grew to 23, and later we went to the neighbor islands and grew to four hundred in three years,” said Medallon.

“We needed to have a voice at the Legislature,” recalls Medallon. “I talked to Waipahu State Representative Mits Shito and told him the story. Ben Cayetano and Neil Abercrombie became our supporters on the Senate side. The concern was unlicensed homes and training. Legislation was approved to require mandatory licensing and training. In turn, the State increased their share because the State matched whatever the resident could pay. I organized nine bus-loads of care givers and rallied in front of the State Department of Human Services, which was in charge.”

Medallon retired from the industry, remarried and carrying the last name (Ka‘ahanui) of her second husband, proudly points to the organized efforts of the care home operators: “It was a learning experience for care home operators; they became more empowered. That was the beginning.”

In the end, when one needs to decide what to do about an aging parent or family member, remember there are many other aspects of caregiving such as home health care, medical supplies, respite care, etc. But not everyone can be a caregiver. “As Filipinos, we like to take care of our families,” says Ulep. “But not all families are trained to handle these situations. They don’t have all the tools or knowledge. Sometimes the elderly hurt themselves or the family gets sick and stressed because they don’t know what to do or how to take care of their elderly.”

Indeed, knowledge, patience, and commitment are key qualities needed as a caregiver.

The Fil-Am Voice thanks all caregivers for their knowledge, patience, commitment, and love.

Alfredo G. Evangelista is a graduate of Maui High School, the University of Southern California, and the University of California at Los Angeles School of Law. He is a sole practitioner at Law Offices of Alfredo Evangelista, A Limited Liability Law Company, concentrating in estate planning, business start-up and consultation, non-profit corporations, and litigation. He has been practicing law for 30+ years (since 1983) and returned home in 2010 to be with his family and to marry his high school sweetheart, the former Basilia Idica.