Our ongoing immigration debacle: How the “RAISE” Act will negatively affect family-based immigration.

Immigration as cheap labor is central to the Filipino story in Hawai‘i. Much attention in the national debate has been on providing relief to people who were brought illegally as minors—the so-called Dreamers. Anecdotally, Filipinos may form a substantial number of Dreamers in Hawai‘i, so there’s certainly some local interest in reaching a solution.

Immigration as cheap labor is central to the Filipino story in Hawai‘i. Much attention in the national debate has been on providing relief to people who were brought illegally as minors—the so-called Dreamers. Anecdotally, Filipinos may form a substantial number of Dreamers in Hawai‘i, so there’s certainly some local interest in reaching a solution.

The other main themes of the national debate—favoring workers with certain skills and knowledge and abandoning family unification as a central idea—gives me pause. And knowing how Hawai‘i’s Filipinos have immigrated to America, should give the entire community pause.

Photo courtesy Gil Keith-Agaran

My family hails from the Badoc-Pinili region of Ilocos Norte—Napu and Puzol. Over the early part of this year, my Texas-born spouse travelled the coastal provinces with my mom hosted by various members of my extended clan. My wife laughs when I recall my last visit to the Philippines preceded the first Martial Law period during the visit of Pope Paul VI. We took a bus from Manila to Puzol—I don’t know if there were flights to Laoag at that time. My wife’s trip showed her the modest, rural, farming roots of my family.

The story of Sakadas in Hawai‘i rarely notes the role of racism nowadays. But Asians historically have been treated as “other” when it comes to American immigration. There were Chinese Exclusion Acts, wartime caricatures of the Japanese, and open prejudice against the Filipino stewards, cabin boys and musicians who found their way to America.

The story of Sakadas in Hawai‘i rarely notes the role of racism nowadays. But Asians historically have been treated as “other” when it comes to American immigration. There were Chinese Exclusion Acts, wartime caricatures of the Japanese, and open prejudice against the Filipino stewards, cabin boys and musicians who found their way to America.

The arrival of fifteen plantation workers aboard the S.S. Doric on December 20, 1906 marks the formal beginning of Filipino migration to the islands. The Hawai‘i Japanese community will be commemorating the 150th anniversary of the first plantation laborers from their native land. There’s some suggestion that the sugar barons looked to the Philippines as a source for workers in part because the Japanese were drifting towards union organizing.

Some one hundred twenty thousand Sakadas arrived in Hawai‘i between 1906 and 1946. My grandfather Lino Agaran arrived in 1928 and my dad Manuel Coloma was part of the largest final cohort of 1946. Today, Filipinos and part-Filipinos have overtaken Japanese as the largest ethnic minority group in the State of Hawai‘i, making up an estimated 14–16% of the population. Census data indicates that nearly half of Hawai‘i’s foreign-born population are Filipinos.

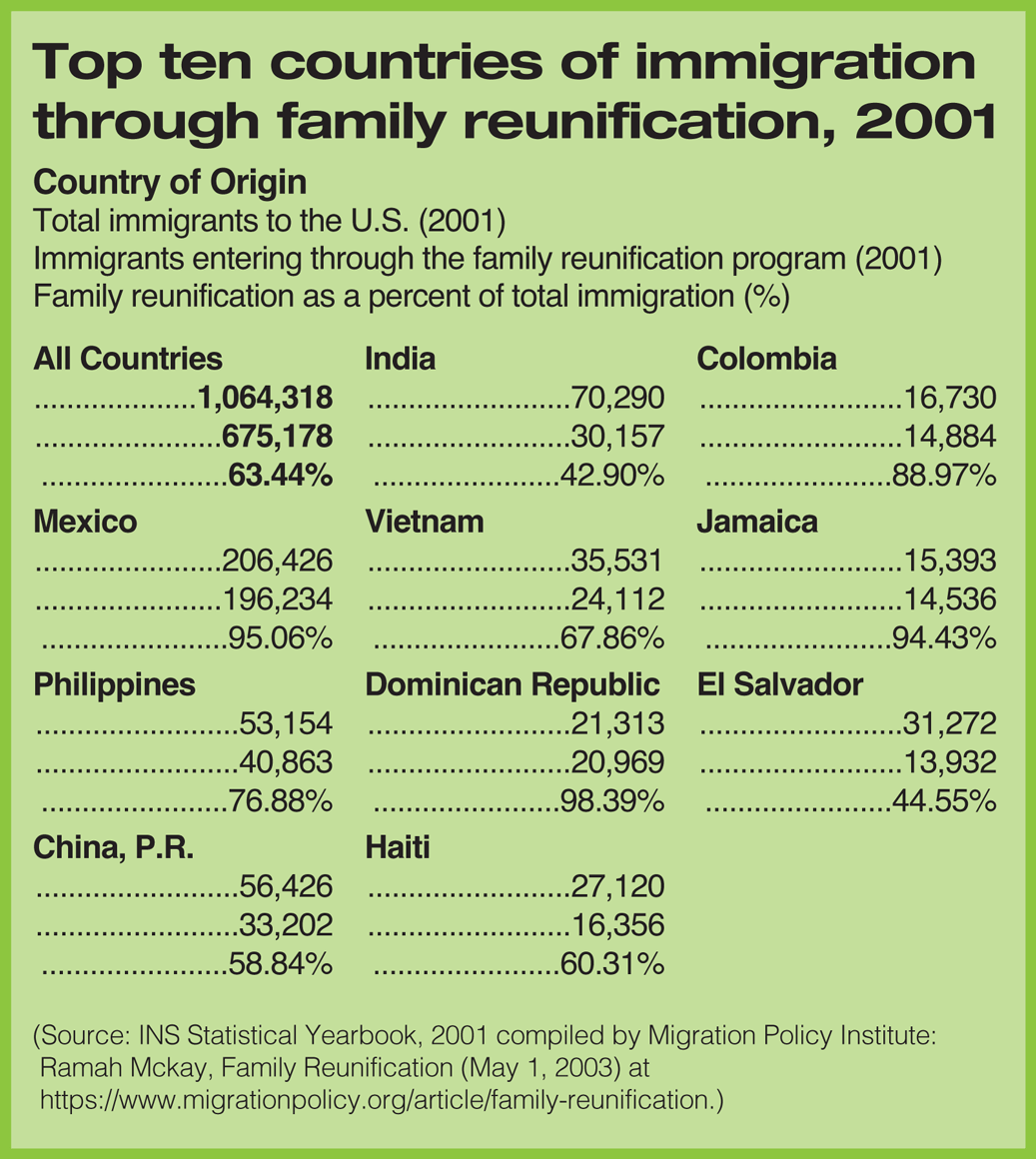

Family reunification remains the largest category for applicants to get “awful permanent residence.” Relatives “ordered” account for approximately two-thirds of total permanent immigration.

Critics of current legal immigration patterns are re-branding family reunification as something called “chain migration.” So it’s clear that the recent proposals by Republican lawmakers and supported strongly by the current U.S. President will impact the major avenue for Filipinos. The most radical proposal, the Reforming American Immigration for Strong Employment (RAISE) Act would make dramatic cuts to legal permanent immigration. While people are skeptical about RAISE moving forward this year, there have been few vocal champions in the minority party’s leadership to support the existing policy favoring family-based immigration. During the 2013 debates, Hawai‘i’s Senior U.S. Senator Brian Schatz and U.S. Senator Mazie Hirono (who herself was an immigrant) emphasized the historic role that family unification has played in immigration.

RAISE makes deep cuts to family-based immigration and creates a points system for the selection of immigrants coming through employer sponsorship. The shift from family unification will fall hardest on U.S. residents seeking to bring in relatives from countries like the Philippines where many come from the same modest, rural towns that produced Hawai‘i’s Sakadas.

Family reunification remains the largest category for applicants to get “lawful permanent residence” in the United States and accounts for approximately two-thirds of total permanent immigration to the U.S. annually. The other ways are employment-based immigration, refugees and asylum seekers, and diversity-based immigration (or the so-called lottery). *See green chart at lower left.

Family unification allows a citizen to petition for “immediate relatives” or sponsor certain relatives. Immediate relatives include non-native spouses and unmarried minor children (aged 21 or under), orphans adopted, and the parents of U.S. citizens. Immediate relatives have no numerical ceiling or quota.

Family sponsorship, in contrast, has four categories with caps on the total numbers allowed: (1) Unmarried, adult children; (2) Spouses and unmarried children of U.S. permanent resident aliens (“green card holders”); (3) Married children; and (4) Brothers and sisters. The total number from any one country is also limited.

After Statehood, the Filipino workers sought to bring family to Hawai‘i. They did so generally through family unification provisions. My grandfather lived most of his 96 years in Hawai‘i. He “ordered” his unmarried daughter—my mom. His cousins also petitioned for their family members. After my parents married, they ordered my father’s brothers and their families, and some of the cousins she was raised with in the provinces. Each of the people who made it through the process then scraped and saved at their jobs to afford bringing other relatives to the islands. The relatives who came to Hawai‘i took the entry-level laborer jobs, including field jobs, that no longer appealed to the children of Sakadas and other Hawai‘i residents.

The family unification process often means waiting for many years. Family unification is what actually introduced me to first cousins—most of the “cousins” I grew up with in the islands were actually second or third or very distant members in the chain of relationships that makes up my extended clan. And while we had some professionals—a smattering of nurses, lawyers and engineers, most of my family both in Hawai‘i and in the Philippines were farmers like my grandfather and father.

As Congress begins “debate” on immigration, I hope someone remembers that most immigrants—Asian or not—came over because a relative petitioned for them. And many of those forebearers would not qualify under the more narrow categories for immediate relatives being proposed.