BOLO MEN–Spirit of the Filipinos

Alfredo G. Evangelista | Assistant Editor

“He was a bolo man in WW2.” That single phrase in the obituary of Stanley “Islao” Magbual piqued the interest of my neighbor and former Maui News Editor Lee Imada who encouraged me to author a story about The Bolo Men of the Philippines. Imada said there was little information on the internet about The Bolo Men.

The original Bolo Men of the Philippines began during the time of the Katipunan, founded by Andres Bonifacio and others. Later, Emilio Aguinaldo was declared president of the short-lived Philippine Republic. All of this occurred during the Philippine Revolution (1896-1898), the Spanish-American War (1898) and the Philippine-American War (1899-1902) characterized as the Philippine Insurrection from the United States’ perspective. Because rifles were scarce, Filipinos armed themselves with large bolo knives that could instantly cause decapitation.

During World War II, Filipino guerilla fighters—again due to the scarcity of munitions—armed themselves with bolo knives to fight against the Japanese Imperial forces. (Even here on Maui, The Maui News reported each member of the Maui Volunteers, Company M, 3rd Battalion (representing Hāli‘imaile) was initially armed with a bolo knife made by the volunteers themselves in Maui Pineapple Co.’s blacksmith shop. Eventually all Maui Volunteers were equipped with a .30-caliber infantry rifle.)

According to his family, Magbual was seventeen years old when he “joined as a Bolo man during World War II against the Japanese. He was appointed to be a Chief Officer because the first commander was too afraid to complete the duties. As CO, he led the men and women at night to do their rounds in the mountain and their surrounding neighborhood. During the day, they guarded the bit-ang (rural unpaved road); collected bituang fruit and extracted the juice; then cooked the juice until it turned to oil. They used cord, or old clothing, as a wick and used this as their light when they made their rounds in the mountain. They also learned to speak basic Nippongo (Japanese). They were called bolo men because their only weapon was a bolo knife and boomerang made of bamboo. The boomerang was so sharp, it could cut a person in half.”

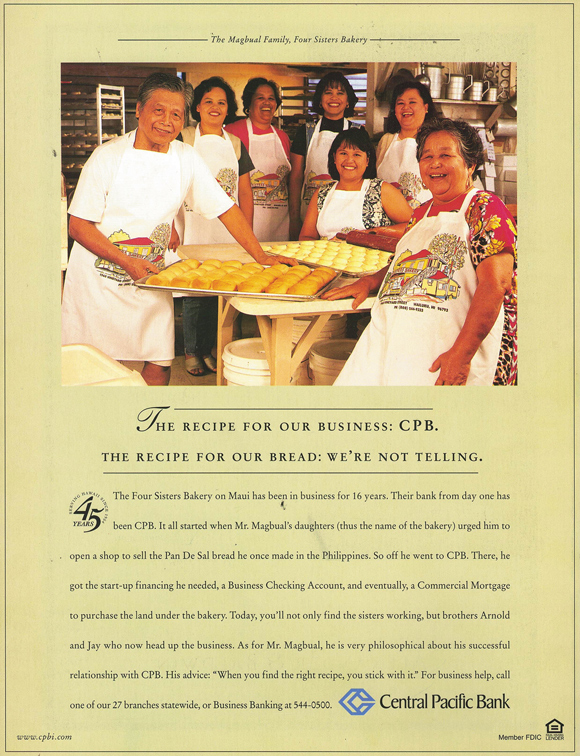

After the war, Magbual moved to Manila, learned the bakery trade and joined his sister Juana Cajigal in Maui in 1979. After initially working as a carpenter, he supplemented his family income by baking. In 1983, Magbual opened Four Sisters Bakery … and the rest is pan de sal and ensaymada history.

April 28, 1924 – January 31, 2023

But the stories of the Bolo Men are quite sparse. During her interviews of Sakadas and their offspring, Lucy Peros can’t recall mention of the Bolo Men. A few stories exist but unfortunately, with each of their passing, the memories fade.

Jared Agtunong’s initial inquiry with his family members appeared to produce little results but he dug further by calling his uncle in the Philippines who gave Agtunong a long and beneficial lesson about his family’s history. “There are actually a total of three family members who were connected to the Bolo Men. WWII’s impact in the Philippines was a push for migration for my family and many other Ilocano people to migrate from the Ilocos Region towards the Mountain Provinces in the landlocked areas of Luzon,” says Agtunong. “My paternal great grandfather Faustino Sagisi from Bacarra, Ilocos Norte served as a Bolo Man in Atok, Flora, Apayao formerly known as Atok, Luna, Mountain Province. Prior to the Japanese occupation, he worked as a rice farmer. I learned that after the war, his spouse, my paternal great grandmother Gregoria Agngarayngay Sagisi received a pension from the United States government as compensation for his efforts during WWII.”

Agtunong also discovered his paternal uncle’s father-in-law Alejandrino Foronda from San Emilio, Ilocos Sur served as Mayor for San Emilio after the Japanese occupation. “During the war, his primary role was to help American soldiers in understanding the geography of the region and as a scout for possible Japanese military camp sites,” states Agtunong. “My uncle also disclosed my paternal grandfather’s sister Eugenia Agtunong, who was born in Batac, Ilocos Norte, played a role during WWII. She cooked food and did the laundry for American soldiers in Flora, Apayao. She made a claim for U.S. pension benefits but due to lack of documentation, never received any benefits/compensation for her role during the war.”

Photo courtesy Magbual ‘Ohana

“My late maternal grandfather Dionicio Ramos Tomas of Solsona, Ilocos Norte was a bolo man,” says Victoria Juan Watanabe. “I remember my late Mom Candida Tomas Juan telling me stories of the war. She was a teenager at that time. She says my grandfather who was a barangay official also was a bolo man. The Japanese came to Ilocos Norte and they would behead those who would steal stuff. My grandfather would try to be a peacemaker and tell the Japanese who among the villagers were not involved in the stealing. By doing that, my grandfather was able to prevent the Japanese from beheading villagers. As a bolo man, he served as a lookout—a sentry—to warn the villagers when the Japanese would be approaching the village so they could avoid any unnecessary confrontation.”

“My paternal granduncle Temotio Ganal Ramos was a bolo man,” says Jeny Ramos Bissell. “He is the brother of my paternal grandfather Juan Ganal Ramos, the father of my Tatang Ricardo Ramos.” Bissell’s aunt Rosita Ramos Agmata, the sister of Ricardo Ramos, recounted to her the stories of the war. “A lot of decapitation, limb amputation, cutting off ears, drinking and eating their own body waste, forceful drinking of water and other liquids.” The relatives of Bissell’s husband Michael were physicians who cared for the guerilla fighters in Manila and nearby villages. Michael Bissell believes the San Fernando, La Union relatives of his Lolo DeGuzman (who was a Judge) were guerilla fighters.

Although Josephine Alvarez Baggao’s family did not include any bolo men, she recalls an interesting story. She was about five or six years old during WWII. “Ferdinand Marcos and about fifteen bolo men came to my grandpa Doroteo Alvarez’ house to hide from the Japanese soldiers,” she recalls. “So they hid under the house. My grandpa Doroteo was a councilman in Davila, Pasuquin, Ilocos Norte and was a friend of Marcos. Early the next morning, Marcos and his bolo men group left to hide in the mountains.”

Photo: Alfredo G. Evangelista

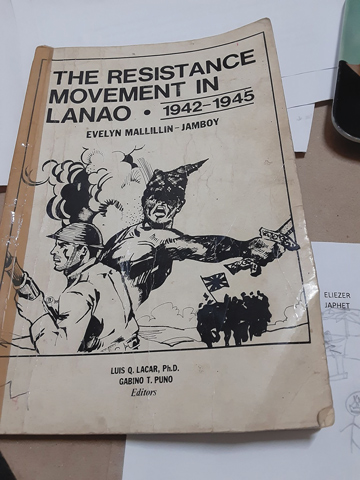

The Bolo Men existed throughout the Philippines. In the province of Lanao Del Norte, Bolo Men were known to be fierce defenders of their province and region. Sharon Zalsos Banaag found a pamphlet titled “The Resistance Movement in Lanao: 1942–1945” authored by Evelyn Mallillin-Jamboy which includes a description of how a certain Mr. Zalsos vowed to eat the liver of any captured Japanese soldier. Zalsos Banaag notes Mr. Zalsos was a distant relative.

Zalsos Banaag heard stories from her grandfather. “According to my Lolo Felipe Abonales Zalsos, World War II was an excruciatingly painful time,” explains Zalsos Banaag. “He was in the Philippine Army at the time. The Japanese captured his regiment. Coincidentally, at the same time, my husband’s mom and her sisters were visiting Mindanao. The three Almerida sisters who were born in Pā‘ia, Maui went to Mindanao to visit relatives but got stuck during the War. Accounts from both my Lolo and mother-in-law painted a horrifying time in the history of Mindanao. Women were brutally raped and killed. Their grandma cloaked the sisters and put them in hiding for months, so no Japanese soldiers found them. News spread fast on the unspeakable atrocities committed by the invading soldiers on women, infants and children and made laborers of the surviving men. It was especially hard on my Lolo to be in captivity. He would tell me in Visayan ‘the gruesome Japanese invasion broke my spirit.’ During this time, my Lolo and his fellow soldiers underwent rigorous training by the Japanese forces. Select captured soldiers were taught to read and write in Kanji.”

Photo: Alfredo G. Evangelista

Arnel Alvarez’ paternal grandmother’s brother Pedro Unite Alonzo was a guerrilla fighter and was captured by the Japanese. “They tortured him by hitting him with the bottom of a rifle and pouring water in his mouth while he was lying down,” says Alvarez. “He survived the Bataan Death March by jumping into the side of the hill.”

Bobbie Sensano, the youngest daughter of Magbual, recounts how her Dad said “the Japanese were notorious and had no mercy. My Dad said if you got caught doing something against the Japanese, they will behead you in front of your family members. And if they caught a glimpse of any of the family members turn their head away in fear, they’ll be next, although my Dad was fortunate not to witness this. This info was passed down from my Dad’s general.”

My wife Basilia’s paternal grandfather Macario Idica was a guerilla fighter from Sinait, Ilocos Sur. The family lore includes the story how her paternal great grandfather Daniel Idica was beheaded by Japanese soldiers in front of Macario. “I remember Grandma Isca reminiscing about great grandpa Daniel knowing how to speak Latin,” says her sister Eugenia Idica Sitts. “He had his Latin books but the Japanese soldiers burnt them. Grandpa Macario said our great grandpa Daniel, who was a barangay leader, was beheaded by the Japanese soldiers because he kept talking in Latin.”

Photo: Alfredo G. Evangelista

Over the years, I understood my Dad, Elias Acang Evangelista, of Paoay (Barrio Sungadan), Ilocos Norte was a guerilla fighter. But I never knew details until recently when I asked my 98-year-old Mom. “Yes, he was a bolo man,” she tells me in Ilocano. “There were many of them, including your uncles Juan Espirito and Tony Acang.” (Espirito and Acang would later be on the S.S. Maunawili with my Dad when they came to Hawai‘i in 1946 as part of the last batch of Sakadas.)

My Mom tells me how all the men from Paoay would hide in the mountains. From the top of the mountains, they could see the Japanese soldiers coming and would warn the villagers. One day, a single Japanese soldier came to the Sungadan barrio, looking for men. My Mom recalls telling him in Ilocano, “You’re by yourself, if you come closer, I’m going to hurt you.” Apparently, the Japanese soldier was accompanied by Ilocanos so the Japanese soldier quickly fled. My Mom chuckles when she recalls that story.

The Japanese soldiers would look for women to be comfort women, according to my Mom who remembers a lady who moved to Manila returned to Paoay only to be forced to be a comfort woman for the Japanese army. (When I get my Mom going, she is full of interesting and sometimes funny stories. She says a lady named Tomasa was at one time my Dad’s girlfriend. Tomasa’s family wanted a thousand pesos but my Dad said he didn’t have that kind of money. When my parents got married the Tomasa family asked my Mom how much money she gave my Dad and she retorted she was not for sale!) After the war, my Mom recalls all the guerilla fighters turned in their bolo knives at the elementary school where my Lila Yadocia Evangelista was a teacher.

Image: FilVetRep

“I always knew he was a bolo man,” says Sensano of her late Dad. “I heard it growing up but I didn’t know all the details until he told me last year. I spoke to him in Filipino and I asked him a lot of questions because I was intrigued.” Sensano says her grandma was so worried about her Dad being a commander. “She begged him to step down. But my Dad was brave. He would lead a group of men to do their rounds in the mountain and jungle at night using a makeshift lantern made of old clothing or cord as a wick and oil from the bituang tree for light. My Dad proudly said he was ready to use his weapon if he needed to and fortunately he never got to use it. He spoke about how the Japanese would walk around during the day. He said he never got to use his skill to use the boomerang or bolo knife because the Japanese were very courteous whenever he had an encounter with them. In fact, he said the Japanese would bow to him when they saw him posting or guarding his station or bit-ang. My Dad in return would salute them.”

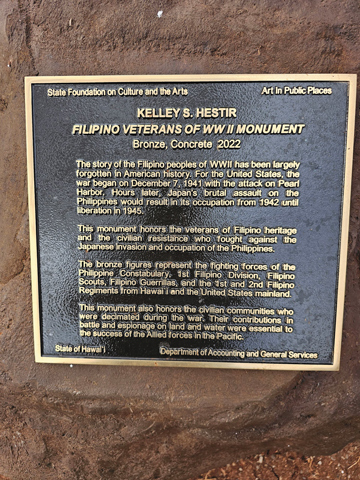

Recently, the Hawaii State Foundation on Culture and the Arts unveiled the Filipino Veterans of WWII Monument. The monument created by Kelley S. Hestir consists of four statues and is on the grounds of the Waipahu Public Library.

Ninety-nine-year-old Art Caleda, a Bolo Man, was in attendance along with his fellow Filipino veterans Oscar Bangui and Faustino Garcia, who is 100 years old. Caleda and many other Filipinos fought alongside the Americans based on President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s promise of citizenship, later rescinded by Congress. In 1992, Caleda and thousands of other Filipino veterans descended in Hawai‘i—without any place to go—to apply for U.S. citizenship. Those Filipino veterans and their families—as many have now died—continue to fight for their benefits. Congress did pass legislation authorizing a paltry sum of money and the award of a Congressional Gold Medal. But there was only one Gold Medal made and Veterans—unless they found a sponsor such as FilVetRep through Retired Major General Antonio Taguba—purchased their own set consisting of a bronze replica of the medal, a case and a copy of the law for $100. In 2020, however, the price increased to $235.

Photo: Sharon Zalsos Banaag

The plaque of the Filipino Veterans of WWII Monument states: The story of the Filipino peoples of WWII has been largely forgotten in American history. For the United States, the war began on December 7, 1941 with the attack on Pearl Harbor. Hours later, Japan’s brutal assault on the Philippines would result in its occupation from 1942 until liberation in 1945. This monument honors the veterans of Filipino heritage and the civilian resistance who fought against the Japanese invasion and occupation of the Philippines. The bronze figures represent the fighting forces of the Philippine Constabulary, 1st Filipino Division, Filipino Scouts, Filipino Guerrillas, and the 1st and 2nd Filipino Regiments from Hawai‘i and the United States mainland. This monument also honors the civilian communities who were decimated during the war. Their contributions in battle and espionage on land and water were essential to the success of the Allied forces in the Pacific.

Indeed, the Filipinos’ role in World War II—and the bravery of the Filipino soldiers including the Bolo Men—is not told as often and as publicly as other soldiers. We must continue to share these stories with our family members so these stories can be retold in the proper context: Filipinos have the spirit to defend their country and their beliefs—no matter the cost–and sometimes, armed only with a bolo knife.

Evangelista recently visited the monument in Waipahu. In addition to the plight of Filipino veterans, he believes one of the untold stories is that of the Filipino community who assisted the veterans who began arriving from the Philippines in 1992 without a place to stay, causing many of them to be briefly housed at the Philippine Consulate General. Community leader Mila Medallon continuously advocated and assisted these Filipino veterans—even to this day despite her failing health. She is an unsung hero in helping to tell these untold stories.

Evangelista recently visited the monument in Waipahu. In addition to the plight of Filipino veterans, he believes one of the untold stories is that of the Filipino community who assisted the veterans who began arriving from the Philippines in 1992 without a place to stay, causing many of them to be briefly housed at the Philippine Consulate General. Community leader Mila Medallon continuously advocated and assisted these Filipino veterans—even to this day despite her failing health. She is an unsung hero in helping to tell these untold stories.