U.S. Supreme Court Eliminates Race Conscious Policies In Selective College Admissions

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran

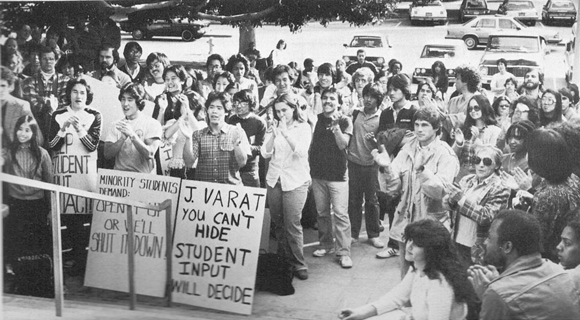

On June 28, 2023, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) issued expected rulings against race-conscious college admissions, handing down 6-3 and 6-2 decisions in two cases, Students for Fair Admissions Inc v. Presidents and Fellows of Harvard College and Students for Fair Admissions Inc v. University of North Carolina. The plaintiff in both, Students for Fair Admissions (SFA), is an anti-affirmative action group created to pursue the suits on behalf of students and their parents who alleged systematic discrimination against Asian American applicants. SFA alleged that compared with other racial groups, Asian American applicants consistently received lower “personal ratings”—for traits like self-confidence, likability and kindness.

The Court’s six Justice conservative majority ruled Harvard’s and the University of North Carolina’s (UNC’s) affirmative action policies failed the Equal Protection Clause’s “strict scrutiny” requirement when employing a racial classification and therefore violated the 14th Amendment of the Constitution. In short, SCOTUS rejected Harvard’s and UNC’s use of race as one of many considerations in trying to admit a student body that reflects the diversity of the nation. The newest Justice, Ketanji Brown Jackson, recused herself in the case against Harvard, but took part in the case against UNC.

Photo: Fred Schilling, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

Forty-five years ago, the Court established in Regents of University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978), that a university’s use of racial “quotas” in its admissions process was unconstitutional but a school’s use of “affirmative action” to accept more minority applicants was constitutional in some circumstances. In 2003, the Court confirmed universities could employ a “system of holistic review”—an admissions approach that did not mechanically assign points but rather treated race as a relevant feature within a student’s application. Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003). Writing for the majority in a case involving admission to the University of Michigan Law School, then-Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote, “Effective participation by members of all racial and ethnic groups in the civil life of our nation is essential if the dream of one nation, indivisible, is to be realized.” Further, O’Connor suggested, “Access to legal education (and thus the legal profession) must be inclusive of talented and qualified individuals of every race and ethnicity so that all members of our heterogeneous society may participate in the educational institutions that provide the training and education necessary to succeed in America.” Justice O’Connor, however, noted twenty-five years had passed since Bakke, and suggested, “We expect that twenty-five years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary.”

Twenty years after Grutter, the decisions in the SFA challenges were not surprising. Chief Justice John Roberts, who assigned himself to write the opinion for the majorities, and Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito previously dissented when SCOTUS upheld affirmative action programs in 2016. Then-Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote for a 4–3 majority to affirm the principles in Bakke, asserting, “A university is in large part defined by those intangible ‘qualities which are incapable of objective measurement but which make for greatness’ … Considerable deference is owed to a university in defining those intangible characteristics, like student body diversity, that are central to its identity and educational mission.” Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, 579 U.S. — (2016). “But still,” Kennedy recognized, “it remains an enduring challenge to our nation’s education system to reconcile the pursuit of diversity with the constitutional promise of equal treatment and dignity.”

Photo: Wikipedia Commons: flickr.com-photos-ellenmetter-14403017345

With the addition of Donald Trump appointees Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, the new conservative “super majority” just last term in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022) overruled longstanding precedents Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973), and Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992) that granted women a constitutional right to abortions in the first trimester of a pregnancy.

In the majority opinion, Chief Justice Roberts suggested, “At the same time, nothing prohibits universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected the applicant’s life, so long as that discussion is concretely tied to a quality of character or unique ability that the particular applicant can contribute to the university.”

Justice Jackson dissenting in the UNC case, joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, wrote: “With let-them-eat-cake obliviousness, today, the majority pulls the ripcord and announces ‘colorblindness for all’ by legal fiat. But deeming race irrelevant in law does not make it so in life.” Justice Sotomayor, dissenting in the Harvard case, declared, “Ignoring race will not equalize a society that is racially unequal. What was true in the 1860s, and again in 1954, is true today: Equality requires acknowledgment of inequality.”

Photo courtesy Alfredo Evangelista

Roberts also wrote, “Nothing in this opinion should be construed as prohibiting universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration or otherwise.” But the Chief Justice warned that admissions officers could not employ the personal essay as a proxy to consider the applicant’s race. “In other words, the student must be treated based on his or her experiences as an individual—not on the basis of race,” he wrote. “Many universities have for too long done just the opposite.” How universities committed to maintaining student body diversity can comply in practice was not spelled out and likely will end up in further litigation.

The affirmative action rulings will have little actual effect locally. The University of Hawai‘i (UH) has three four-year campuses: UH Hilo, UH West O‘ahu, and the flagship UH Mānoa. Mānoa reportedly has a somewhat selective admission rate of 58 percent, with West O‘ahu accepting 84 percent of applicants, and Hilo taking 71 percent. In comparison, the most selective institutions like Princeton, Harvard, Stanford, Massachusetts Institute of Technology and California Institute of Technology accept approximately 3 percent of applicants, with Yale admitting 5 percent, and Brown, Dartmouth, Pennsylvania, Duke and Chicago taking 6 percent.

And that’s the rub for the selective American colleges and universities. As New York Times reported (Sarah Mervosh and Troy Closson, “The ‘Unseen’ Students in the Affirmative Action Debate,” New York Times 7/1/2023 [https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/01/us/affirmative-action-students.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share&referringSource=highlightShare]), the decision will impact elite college admissions, reducing the number of Black and Hispanic students at the most selective American universities. As in the case when California barred affirmative action by referendum in 1996 (Proposition 209), the University of California system—especially at the most selective Berkeley and UCLA. campuses—saw sharp drops in the number of Black and Hispanic students admitted.

Photo courtesly Alfredo Evangelista

As Mervosh and Closson note, “But the effect of race-conscious admissions was always limited to a relatively small number of students. For the vast majority of college aspirants, those elite schools are not an option—academically or financially.”

The Times reported, “Many head straight into the work force after high school or attend less selective universities that do not weigh race and ethnicity in admissions. Approximately a third of all undergraduate students—including half of Hispanic undergraduates—attend community colleges, which typically allow open enrollment.”

UH Maui College offers a smattering of four-year degrees along with partnering with other campuses to allow Maui residents some classes using remote learning to earn credits towards four-year degrees. Compared with mainland schools, UH likely has a more demographically diverse student body. Student bodies at the four-year campuses, however, do not reflect the statewide number of native Hawaiians and Filipinos. Like Blacks and Hispanics on the continent, many Hawaiians and Filipino students attend the community colleges scattered throughout the islands, if they pursue any higher education at all. But Bachman Hall leaders continue to favor Mānoa—even complaining that the recently approved State Budget favored the community colleges at the expense of Mānoa.

Further, the Times observed, “Fewer than 200 selective universities are thought to practice race-conscious admissions, conferring degrees on about 10,000 to 15,000 students each year who might not otherwise have been accepted, according to a rough estimate by Sean Reardon, a sociologist at Stanford University. That represents about 2 percent of all Black, Hispanic or Native American students in four-year colleges.”

The impact of the Court decision will fall more on promising Hawai‘i students applying to elite and selective mainland schools. While islanders likely will continue to benefit from policies that favor a geographically diverse class, local high school graduates will need to pay attention to what factors mainland schools will choose to emphasize. Institutions even before the recent Harvard and UNC litigation have increasingly recognized high-achieving students from low-income families or “first-gen” applicants—the first in their families to go to college. The schools practicing affirmative action likely have been working towards “race-neutral” admissions for some time, and personal essays and recommendations may play a larger role in seeking diverse classes.

Adam Harris, in his 2021 book, The State Must Provide: Why America’s Colleges Have Always Been Unequal—and How to Set Them Right, suggested restricting or abolishing affirmative action simply restores the unequal access to elite higher education that has always existed. Harris argues, reviewing history, from its inception, America’s higher education system was not built on equality or accessibility, but on educating—and prioritizing—white students. Even the system of Historic Black Colleges and Universities created to provide places for Black students never received the same amount of state support as the predominantly white schools of higher education located in the same state.

Yale President Peter Salovey wrote to alumni shortly after the decision. “Yale,” he asserted, “is committed to continue this journey and build on the progress we have achieved together.” Yale joined several other universities in an amicus brief, arguing “diversity vitally enhances higher education. A student body that is diverse across every dimension, including race, improves academic outcomes for all students, enhances the range of scholarship and teaching on campus, improves critical thinking, and advances the understanding and study of complex topics. Generations of Yale students, alumni, faculty, and staff can attest that Yale’s diverse educational environment has positively contributed to their creativity, adaptability, and leadership.”

Salovey asserted, “A whole-person admission review process that takes into account every aspect of an applicant’s background and experiences has enabled colleges and universities to admit the classes they need to realize their missions. Restricting this ability limits universities in opening their doors to students with the widest possible range of experiences. This is a detriment to everyone who benefits from the diversity of our campuses.”

Jeremiah Quinlan, Dean of Yale Undergraduate Admissions and Financial Aid, also contacted alumni: “Today’s rulings will not change our commitment to consider each applicant as a multi-faceted individual. Yale’s whole-person review process is one of the College’s great strengths and has yielded student and alumni bodies that reflect the enormous depth and breadth of humanity. This approach enables admissions officers to consider the many factors that shape each applicant’s candidacy, and for decades it has helped the admissions committee select students who will make the most of a Yale education while making significant contributions to the Yale community.”

Quinlan noted, “Whole-person review has also helped make Yale more accessible. Today, the number of students who are eligible for the Pell Grant, a federal grant awarded to undergraduates with exceptional financial need, is nearly twice as high as it was a decade ago, and the numbers of undergraduates who identify as people of color, and those who will be the first in their families to attend college, have both increased by more than 60 percent over the past ten years.”

The California schools clawed back some of the enrollment decreases by investing in more extensive and expensive recruiting efforts while employing race neutral admissions policies. Starting in the early 2000s, the top-performing students graduating from most high schools in the state were guaranteed admission to most of the eight UC undergraduate campuses. But as University of California Chancellors informed SCOTUS in amicus briefs supporting Harvard and UNC, despite investing billions, the schools have made some progress but have not met their diversity and equity goals in the twenty-five years since Proposition 209 was approved.

Texas largely sidestepped affirmative action by implementing a program where the top resident students in all Texas public and private schools are guaranteed admission to a University of Texas campus. Texas House Bill 588, commonly referred to as the “Top 10% Rule”, is a Texas law passed in 1997. The law guarantees Texas students who graduated in the top ten percent of their high school class automatic admission to all state-funded universities. With schools in communities that may have larger or homogenous Hispanic and Black populations, top students from those schools have the opportunity to attend a UT campus. The University of Texas at Austin, however, only guarantees admission to students from the top six percent of their high school class. But the Fisher challenge arose despite the Top 10 percent Rule when a white female student missed the cut-off for her high school and she was placed in a pool where race was considered as an admissions feature.

The effort to boost diversity that more closely reflects the California population has come with a heavy price tag. Since Prop 209 took effect, UC has spent more than a half-billion dollars on outreach programs and application reviews to draw in a more diverse student body. Olufemi Ogundele, Dean of UC Berkeley undergraduate admissions, recently reflected in the New York Times, “Those measures run the gamut from outreach programs directed at low-income students and students from families with little college experience, to programs designed to increase UC’s geographic reach, to holistic admissions policies.” (Olufemi Ogundele, “Learn From Those Of Us Doing The Work Already,” New York Times 7/4/23, [https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/07/05/opinion/affirmative-action-college-admissions.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share&referringSource=articleShare]). In the briefs, the California Chancellors wrote, “Yet despite its extensive efforts, UC struggles to enroll a student body that is sufficiently racially diverse to attain the educational benefits of diversity.” The amicus brief notes: “Although these programs have increased geographic diversity, they have not substantially increased the racial diversity of students admitted to UC. They have had little impact at the most selective campuses.”

Ogundele cautions admissions officers face big challenges: “Having equitable college admissions requires an understanding of the broader context of students’ applications, information about their neighborhoods (the College Board’s Landscape is one tool), their schools, the courses available, access to those courses and their situations at home, because experiences vary greatly in K–12.”

Since California eliminated race-conscious admissions, Arizona, Florida, Idaho, Michigan, Nebraska, New Hampshire, Oklahoma and Washington have also barred affirmative action either legislatively or by referendum. Selective public universities in redder states may also face different risks in maintaining “diversity, equity and inclusion” policies where conservative elected officials are quick to label certain practices as “woke” and appear willing to interfere legislatively with admissions policies. Those institutions will have to carefully craft approaches to navigate the narrow route allowed in the Roberts opinion.

The Court decision did not impact another part of the admissions process that was criticized as favoring white and wealthy applicants— so-called “legacy” preferences for the children of alumni and faculty, donors, and athletes. Disgruntled supporters of diversity policies have already filed lawsuits challenging those preferences. Elite schools have resisted those objections, arguing these preferences build community and assist in fund-raising. But with cynicism around college admissions high (especially following the admissions scandal where parents bribed coaches at selective schools to admit their non-athlete children as recruits), elite universities may need to adjust those policies as well.

While race conscious factors are now illegal, the decisions still leave questions for America’s selective colleges and universities. Opponents of affirmative action have already warned they will be watching how those institutions respond.

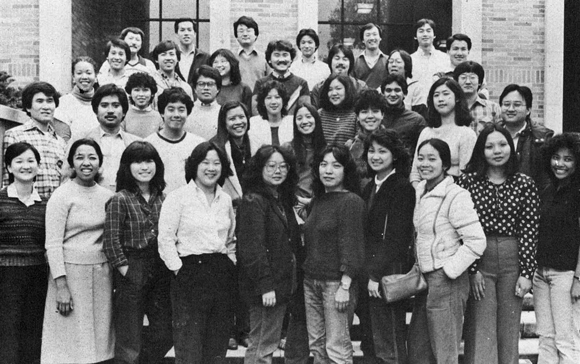

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran, a first generation Filipino-American, was admitted to Yale College two years after the Bakke decision and only twelve years after the admission of the first undergraduate women to Old Eli, and to the Boalt Hall School of Law, the University of California at Berkeley, a dozen years before California voters eliminated affirmative action through Proposition 209. He served as a student member of the Boalt Hall Admissions Committee during his third year in law school. His undergraduate class was quite diverse, with students enrolled from every part of Westchester County. He received degrees from both institutions and practices law in Wailuku. He also represents Central Maui in the Hawai‘i State Senate. UH Maui College is in his Senate district.

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran, a first generation Filipino-American, was admitted to Yale College two years after the Bakke decision and only twelve years after the admission of the first undergraduate women to Old Eli, and to the Boalt Hall School of Law, the University of California at Berkeley, a dozen years before California voters eliminated affirmative action through Proposition 209. He served as a student member of the Boalt Hall Admissions Committee during his third year in law school. His undergraduate class was quite diverse, with students enrolled from every part of Westchester County. He received degrees from both institutions and practices law in Wailuku. He also represents Central Maui in the Hawai‘i State Senate. UH Maui College is in his Senate district.