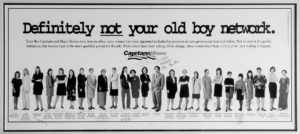

Definitely Not Your “Old Boy” Network

Benjamin Cayetano: First highest-ranking elected official of Filipino ancestry in the State of Hawai‘i: 8th in a series.

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran

Editor’s Note: 2019 marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the election of Benjamin J. Cayetano as the Fifth Governor of the State of Hawai‘i and the first Filipino-American elected as the head of an American state. This is the eighth in a series of articles profiling Cayetano and his historic election and service. Versions of these articles appeared previously in The Filipino Summit.

A photo spread prepared for Governor Cayetano’s re-election campaign shows him flanked by women from the Cabinet, including his running mate Lt. Gov. Mazie Hirono. In both gubernatorial elections, Cayetano faced high-profile women Republican office holders. In 1994, Cayetano upset U.S. Congresswoman Pat Saiki (and Honolulu Mayor Frank Fasi running as an independent) to continue the post-Statehood Democratic near strangle-hood on Washington Place. In 1998, as the economic hangover continued to stretch, Maui’s generally well-regarded and well-spoken but term limited Mayor Linda Lingle announced her expected challenge to Cayetano.

A consistent criticism of Hawai‘i’s post-statehood dominance by Democratic Office holders had been to brand all government as an “old boy network.” Cayetano’s photo ad responded directly to that notion with the tag “Definitely not your old boy network.”

Cayetano ended up winning a fairly close election.

The photo, perhaps to the surprise of even very observant government watchers, reflected that major parts of the Cayetano agenda were in the hands of women.

In filling his initial Cabinet, Cayetano had opened the process—even taking out ads in the newspaper to invite interested applicants for the State departments and agencies slots that he would need to fill. People who worked on his campaign were expected to make themselves available and observers expected some of Hirono’s supporters were likely to apply as well.

“To the surprise of some of his kitchen cabinet—mostly men, Governor Cayetano proved to be a strong believer in empowering women,” his Press Secretary Kathleen Racuya-Markrich remembers. “He appointed the highest number of women department directors and deputies than in past administrations. Attorney General Margery Bronster, Kathryn Matayoshi to run the Department of Commerce & Consumer Affairs (“DCCA”), Susan Chandler in charge of the Department of Human Services, and Mary Pat Waterhouse at Accounting and General services, just to name a few.”

Cayetano raided the middle ranks of the State Bar, tapping a number of younger women lawyers, including Matayoshi at DCCA, Lorraine Akiba at Labor and Industrial Relations, and Bronster at the Attorney General’s Office—three key departments for improving business and economic regulation. None were very well-known outside of their particular social circles or firms.

Years later, Akiba recently observed consistent with other women who served in the administration, “From my perspective, the greatest hallmark of Governor [Cayetano]’s leadership and legacy is the fact that more than any other Governor before or after him, he appointed the most number of women to leadership positions in his Administration, as department directors and agency heads.”

From Statehood onward, the Labor post had been held by various union-friendly officials. Waihe‘e’s last labor director had been United Public Workers official Dayton Nakanelua. Akiba, a litigation partner at one of Honolulu’s major law firms, was the first woman to serve in the post. Despite criticism about her lack of labor law knowledge or union ties, Akiba won confirmation from the State Senate’s reconstituted Executive Appointments committee.

With handling budget challenges paramount for the Governor’s closest operatives at the start of the Administration, Akiba’s contributions addressed the economic recession that could be affected by the Labor Department.

When Kaua‘i sugar operations closed, Akiba helped lead the multi-agency team sent to help workers who would be losing their long-held jobs. “Many of these workers were first and second generation Filipino immigrants who had worked for decades in these industries,” Akiba recalled. As in past closures, “the economic impacts were especially hard for families on the neighbor islands like Maui, Kaua‘i and the Big Island” still slowly undergoing the long economic disruption brought by the closure of the sugar and pineapple operations on those islands.

Akiba perceived that structural foundations included putting into action an effective workforce development strategy. Statewide, major employment sectors like the pineapple and sugar industry continued their decline as Hawai‘i’s large agricultural operations ended. Along with people directly employed by the plantations, the closing of agribusinesses affected their vendors and indirectly impacted the economy of scale for smaller farmers in purchasing inputs that vendors shipped in primarily for the plantation.

Akiba leveraged available federal funds under the Clinton Administration (Job Training Partnership Act and Workforce Development Act programs) to help dislocated workers transition to new jobs and also to provide Unemployment Insurance (UI) and other social safety net support to impacted individuals and families. Akiba also helped to establish the Hawai‘i Employers Mutual Insurance Company (HEMIC) and reform workers compensation insurance—both initiatives aimed at helping Hawai‘i’s small businesses who had been placed in the assigned risk pool and were paying extremely costly premiums with no other options.

While the Governor and Lt. Governor run in separate partisan primaries to determine the party nominees, people assume the Lt. Governor works for the Governor. In 1998, Mazie Hirono ran to become only the second person to serve two full terms as Lt. Governor. Cayetano himself had been the first, waiting in the wings for eight years under Governor John Waihe‘e.

Hirono had been an active Consumer Protection committee chair in the Legislature. Fiery and pointed in the mold of Patsy Takemoto Mink, in introducing herself to statewide Democratic voters, she had reconstituted her image. To the amusement of longtime friends and detractors, many voters perceived Hirono as a calming female AJA figure to balance off the fiery outspoken Filipino at the top of the ticket.

“Governor Cayetano specifically delegated this important task to Lt. Governor Hirono and it was successfully implemented as a result of their teamwork and leadership,” Akiba says. Cayetano had broken a mini-string of Filipino appointees as Labor Director in Alfred Laureta, Joshua Agsalud and Mario Ramil. When Akiba left state government in 2000, the final two years of Cayetano Labor Directors were filled by Filipinos Gil Coloma-Agaran and then Akiba’s and Coloma-Agaran’s deputy director Leonard Agor.

Matayoshi, formerly an attorney at another of the major Bishop Street law firms, came to State government from Hawaiian Electric where she worked as an in-house attorney. Her public service pedigree came from her Big Island roots where her father Herbert had been the second elected Big Island Mayor, holding the post for a decade after several terms on the Board of Supervisors and County Council. Matayoshi’s mother Mary was a teacher who would also hold a post in the Cayetano administration.

Nevertheless, concerns regarding Matayoshi’s work experience plagued the Hilo High School graduate during her confirmation since her department included the Office of Consumer Protection which represented public concerns before the Public Utilities Commission. She won a hard-fought confirmation from the Executive Appointments Committee which vetted all of the new Governor’s Cabinet appointments. Ironically, as a child, Matayoshi had taken hula under the mother of the Executive Appointments Committee chair.

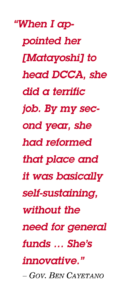

Matayoshi’s major passion was to move DCCA from the paper laden stone-age of government operations to the modern technological age. Like most of government, DCCA remained a paper-intensive agency with hardcopy-oriented processes for the many professions and licenses the department regulated through numerous licensing commissions and boards. When Matayoshi was being considered for Superintendent of Education in 2010, Cayetano endorsed her warmly in the Honolulu Advertiser. “When I appointed her to head DCCA, she did a terrific job. By my second year, she had reformed that place and it was basically self-sustaining, without the need for general funds,” Cayetano was quoted as saying. “She’s innovative.”

Matayoshi’s major passion was to move DCCA from the paper laden stone-age of government operations to the modern technological age. Like most of government, DCCA remained a paper-intensive agency with hardcopy-oriented processes for the many professions and licenses the department regulated through numerous licensing commissions and boards. When Matayoshi was being considered for Superintendent of Education in 2010, Cayetano endorsed her warmly in the Honolulu Advertiser. “When I appointed her to head DCCA, she did a terrific job. By my second year, she had reformed that place and it was basically self-sustaining, without the need for general funds,” Cayetano was quoted as saying. “She’s innovative.”

At the beginning of the Cayetano Administration, DCCA still competed with the rest of government for a share of general tax revenues to fund its various operations. Unlike many agencies, however, the Department generated revenue directly through the licensing and regulatory fees it charged for the numerous professions and businesses that DCCA oversaw, including insurance companies, state chartered financial institutions, real estate brokers and realtors, architects, surveyors, and engineers, contractors, doctors and nurses and others. It also charged for business formation registration and then annual filings for Hawai‘i’s various business entities.

DCCA’s operations were largely based on O‘ahu so neighbor island businesses, professionals and licensees had to send all their paperwork to Honolulu for processing. Processing of the paperwork often took weeks depending on the workload on O‘ahu.

Matayoshi convinced Cayetano she could make DCCA a more “customer-oriented” department through investments in technology and changes to the statutes and internal operations. Much of state government operated on “legacy” computer desktop systems contracted and purchased from the financially troubled Wang Corporation. The young lawyers and executives brought in by Cayetano from the private sector largely came from law firms and businesses that saw the benefits of investing in modern desktop computers and other technology. Matayoshi also thought she could work with other departments with like-minded leadership—Tax and Labor—to take advantage of available technology upgrades to streamline the process for starting a new business.

A key initiative was to pool all the revenues charged by DCCA into what would become the Compliance Resolution Fund (CRF) to fund all of DCCA’s operations and eliminate Matayoshi’s Department from State general fund support. The CRF basically made DCCA identify its operating expenses and balance those costs against what it collected from the various sectors it regulated and oversaw. The Legislature, without much fanfare or attention, approved the statutory changes and supported Matayoshi’s ambitious effort to rationalize her Department’s operational costs with the fees charged and collected.

The Legislature also approved Matayoshi’s proposed statutory changes to the registration laws for businesses—streamlining the formation of corporations and partnerships and the then-new limited liability entities and adopting the laws in States like Delaware and Nevada that eliminated cumbersome paperwork in establishing new businesses.

The work at DCCA was done quietly and largely out of the limelight but affected most of Hawai‘i’s businesses. One of the biggest changes was allowing more services online using an outside vendor, including registration and business formations. Neighbor islanders now had a choice to have their paperwork processed in a shorter time. Implementation initially required a few days of processing with a fee charged for expediting. After some time, processing time by DCCA’s staff in the regular course drew to the same or close to the expedited time.

During his legislative years, Cayetano was a staunch support of social programs. In filling the top slots at the sprawling Department of Human Services (“DHS”) which covered all government social service programs, he plucked community organizer and social worker Susan Chandler from the University of Hawai‘i. For Deputy Director, Cayetano tapped Kate Stanley, a former State legislator, who had been a key Waihe‘e Governor’s office advisor and a close ally of the newly elected Lt. Governor.

General tax revenues are intended to fund the core functions of state government—education (lower and higher public education), and health, safety and welfare agencies. After education, the Hawai‘i state budget allocated large amounts to social welfare programs. When talking about a budget crisis, large generally funded departments like DHS faced substantial challenges.

With changes to the welfare system high on the national agenda, Cayetano’s new team pursued their own brand of “welfare reform.” Chandler and Stanley established what they called Temporary Assistance to Needy Families. As required by the federal government’s welfare reform guidelines, Hawai‘i changed the cash entitlement for low income individuals to a five year maximum, life-time benefit. Hawai‘i also created a state program called Temporary Assistance to Other Needy Families which provided help to two parent families.

DHS also created several work programs as federal policy encouraged work components for welfare recipients. In one called TOPS, the state departments assisted by hiring or training people on the welfare rolls. DHS also pursued an employment training program. Employers would train people on welfare assistance with the state paying during the training, and then after six months the employer would hire those workers. In connection with the expanded work programs, the Cayetano administration expanded the Pre-school Open Doors programs to support more children whose parents were on welfare.

During the Cayetano Administration, Hawai‘i won prizes by placing in the top five states for Food Stamp accuracy. When Hawai‘i finished first, DHS received a one million-dollar bonus from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Following the trend at DCCA to adopt technological tools, Chandler and Stanley established an Electronic Benefit Card. People on welfare used the card (which looked like a credit card) to buy food and get cash assistance. The cards provided convenience and DHS saved on periodic mailing of hardcopy checks to recipients.

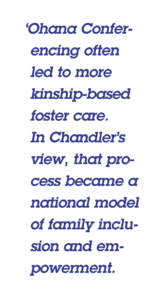

Cayetano’s Human Services department also led a coalition based on a resolution called A Blueprint for Child Welfare reform. It also reduced the number of children in foster care (winning an award from then-First Lady Hillary Clinton for having the largest rate of decline) and established more Point of Service contracts for family support. DHS centralized Child Protective Services (CPS) intake calls across the state. Chandler and Stanley also premiered ‘Ohana Conferencing, a family group decision making process which includes families, and their supporters more respectfully into the CPS process. ‘Ohana Conferencing often led to more kinship-based foster care. In Chandler’s view, that process became a national model of family inclusion and empowerment. Chandler based the process on the Maori model in New Zealand with some aspects of Hawaiian ho‘oponopono.

Cayetano’s Human Services department also led a coalition based on a resolution called A Blueprint for Child Welfare reform. It also reduced the number of children in foster care (winning an award from then-First Lady Hillary Clinton for having the largest rate of decline) and established more Point of Service contracts for family support. DHS centralized Child Protective Services (CPS) intake calls across the state. Chandler and Stanley also premiered ‘Ohana Conferencing, a family group decision making process which includes families, and their supporters more respectfully into the CPS process. ‘Ohana Conferencing often led to more kinship-based foster care. In Chandler’s view, that process became a national model of family inclusion and empowerment. Chandler based the process on the Maori model in New Zealand with some aspects of Hawaiian ho‘oponopono.

Chandler and Stanley also resisted the federal effort to remove non-citizens from Medicaid eligibility. Hawai‘i then as now had a fairly large group of COFA residents who remained on Medicaid throughout the Cayetano years. “We kept using federal funds which turned out to be illegal, so we then used state funds,” Chandler recalls. “[Cayetano’s successor] Lingle kicked them off.”

In short, women leaders played important roles for Governor Cayetano’s efforts to move the State forward despite the general fund budget crisis.

The Cayetano-Hirono Administration actually appointed a woman as director or deputy director in nearly every major department. Others who served included Jobie Masagatani at Hawaiian Home Lands, Letecia Uyehara at Agriculture, Susan Inouye at Taxation, Paula Yoshioka at Health, Rae Loui at the Commission on Water Resource Management, Mary Pat Waterhouse at Accounting and General Services, and Cora Lum at Public Safety. Cayetano’s executive staff included Celia Suzuki, Jan Yokota at Hawai‘i Community Development Authority, Moya Davenport Gray at Information Practices, Marilyn Matsunaga at Health Planning and Development Agency, Press Secretaries Kathleen Racuya-Markrich and Kim Murakawa, Brenda Lei Foster for International and National Affairs, Sheila Forman for Child and Family Policies, Ka‘iulani de Silva for Information Services, Marilyn Seely at Office of Aging, and Mary Matayoshi at Volunteer Services.

“I appreciated the Governor’s genuine commitment to and support for giving women the opportunity to hold leadership positions in his Administration and the fact that he didn’t make a big deal about it,” Akiba says. “He proudly reiterated that these women were the most qualified and experienced individuals for the positions they were appointed to.”

“When he hired me to be his Press Secretary, he told me he wanted a woman for the job,” Kathleen Racuya-Markrich, then a Deputy Attorney General, remembers. Being Filipina wasn’t a factor she recalls.

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran served eight years in the Cayetano Administration at the Departments of Land and Natural Resources, Commerce and Consumer Affairs, and Labor and Industrial Relations. He currently maintains a small law practice in Wailuku, Maui and represents Central Maui in the State Senate.

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran served eight years in the Cayetano Administration at the Departments of Land and Natural Resources, Commerce and Consumer Affairs, and Labor and Industrial Relations. He currently maintains a small law practice in Wailuku, Maui and represents Central Maui in the State Senate.