My House colleague Isaac Choy and I started at the legislature together in 2009. He won election to a vacant seat in November 2008. I was appointed to the Kahului seat when longtime Maui Representative Bob Nakasone passed away.

There were seven of us House “freshmen” in 2009: six elected (Denny Coffman and Mark Nakashima from the Big Island, Chris Lee from Lanikai-Waimānalo, Jessica Wooley from the Windward side of O‘ahu, Henry Aquino from Waipahu and Isaac from Mānoa) and one selected (me).

Isaac came to the legislature as a successful CPA. One of the others worked for a non-profit, one was retired, two of us practiced law, and two decided to become full-time legislators. Two of my 2009 colleagues—the other lawyer and the retiree—left the House after several terms, and in 2013, I left when I was appointed to complete Lt. Gov. Shan Tsutsui’s senate term.

From the start, some of my Maui clients were surprised to learn I continue to live on Maui and I continue to practice law. Unlike the U.S. Congress, the Hawai‘i legislature is a part-time “business,” and its members generally live full-time in the communities they represent and have been elected from. The legislature convenes for sixty floor days annually on the third Wednesday in January. With weekends, holidays and recess days excluded, the legislature adjourns in the first week of May. Legislative committees can meet on floor days as well as recess days and very rarely on weekends and evenings. Votes on bills are taken in committee and then bills passing out of committee get debated and voted on the floor.

As a neighbor islander, during the session I usually fly to O‘ahu on Monday morning and return home to Maui on Friday afternoon. I continue to practice in Wailuku with my law partners Tony Takitani and David Jorgensen. During the session, any legal work I perform for clients has to occur outside of my legislative duties.

Like my 2009 colleagues, the Maui legislative delegation is a mix of part-time legislators like me who have a real job at home, and full-time legislators. Some of the latter are retired like Speaker Emeritus Joseph Souki and Senate Consumer Protection and Health chair Rosalyn Baker. Rep. Lynn DeCoite is a farmer. Others have made legislative work their vocation, with perhaps a family business on the side.

While I’m honored to represent my Central Maui community in the State Senate, I also try to remember that my legislative title doesn’t define me. My primary identity remains husband to my wife, uncle to my adult hanai child, son to my eighty-eight year old mother, brother to my sister, and an active and contributing member of my church and my community.

For myself, my part-time approach to legislating—as well as all the daily advice and reproaches I get from family and friends—keeps me grounded in every day reality. I have to pay my taxes. I deal with water and sewer and refuse collection bills. When the Wi-Fi doesn’t work at home, I gotta deal with the cable company. I shop for groceries and I drop by the post office to check my box. When my niece was still in middle and high school, I served on school-community councils for her schools.

Isaac once suggested that having a real job also impacts how you vote on the hard issues.

It’s a reality that politicians like to be liked. And the ultimate popularity contest occurs on Election Day every two years for State Representatives and every four years for State Senators.

The American idea of representation always includes some balancing between pure democracy and republicanism. Unlike a pure democracy, we do not require a referendum on every issue that comes before the legislature. The tension occurs in the continuum where elected representatives vote as they perceive a majority of their constituents would do so themselves or whether the electeds vote as they themselves believe on the issue. As I noted earlier, legislators like to be liked. They generally lean towards voting as their communities would, including on issues where the legislators might believe differently. Often their view might be based on their election experience where a candidate’s position on a particular issue seemed to effect the result of the election.

Isaac suggests that having real jobs free legislators to vote their consciences on controversial issues. In short, losing the next election because of a vote based on conviction is less of a factor in casting your vote when your personal identity remains outside your political office.

While there’s some truth there, I doubt if anyone—part-time or full-time in office—would disagree that sometimes you just vote your conscience. But as one of my Senate colleagues who has been in public service for over thirty years noted, it really depends on the issue. A prime example was the twenty year debate on Civil Unions and Same Sex Marriage. For many years, Civil Unions couldn’t even get to floor votes because the members of the legislature were conflicted—both because of constituent feelings and their own personal convictions on the issue.

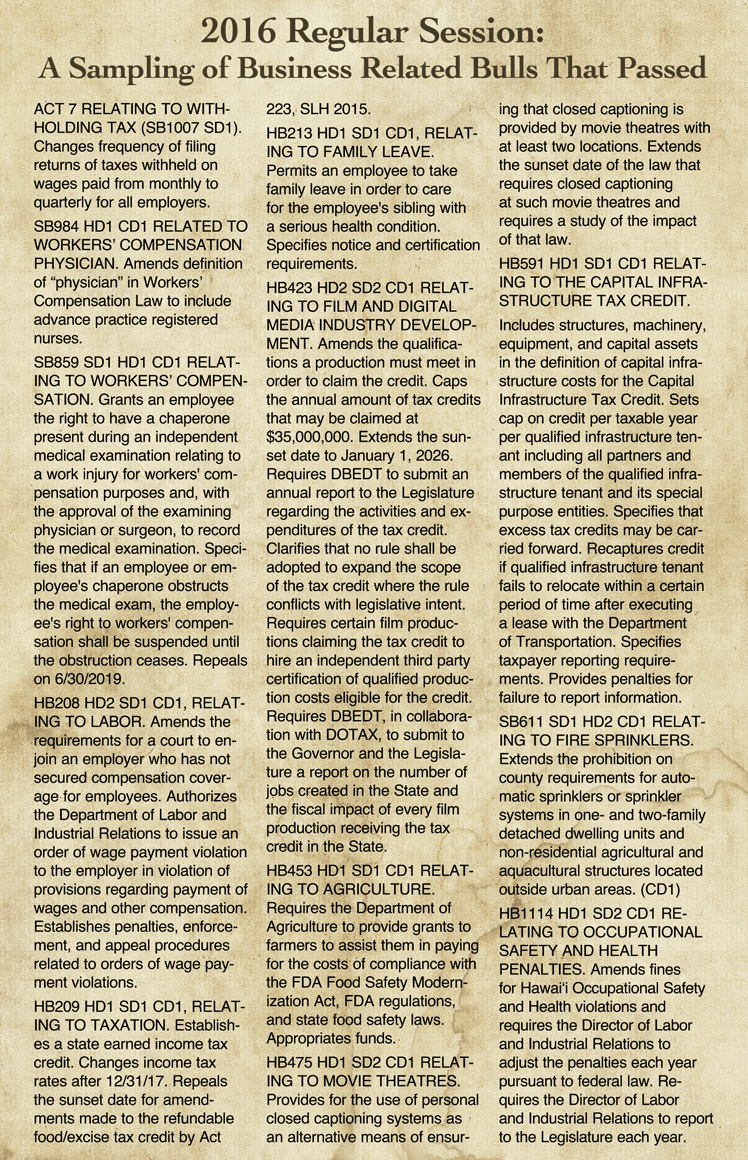

Another example might be bills proposing to raise the minimum wage, requiring paid sick leave, or adding siblings and bereavement as reasons for using unpaid Family Leave. In Hawai‘i, the days of the Big Five are long gone and most companies would be considered small businesses in much of the Country. Certainly on Maui, with the last sugar company now out of its own large-scale mono crop agriculture, the larger employers are hotels and certain construction contractors. Many neighbor island and rural O‘ahu legislators will see bills that affect businesses through the lens of their small business-owning constituents.

My colleague Russell Ruderman runs a successful chain of health food stores on the Big Island. But he’s a consistent voice in support of a higher minimum wage and expanding employee benefits. He brings a progressive view on socio-economic issues that likely reflects the views of many of his Pāhoa-Puna constituents.

It’s not a simple calculation that part-timers will always vote their personal convictions on a controversial issue. Some issues have greater importance in certain districts and islands. Rail is one of those issues and neighbor island legislators perceive the pros and cons differently from the O‘ahu residents who are paying the GET surcharge and either living with the burdens and benefits of years of construction or not. In August, the entire legislature will convene a special session to take up the funding of O‘ahu’s rail project.

Isaac recently sold his CPA business and retired. He’s effectively become a full-time legislator now. At the end of the upcoming session, he and the other three remaining members of the 2009 class will have served ten years in the House—five terms. All four have served as committee chairs and found themselves over time as in the controlling House coalition and outside it.

I’m still practicing law and telling myself that my primary identity remains husband to my wife, uncle to my adult hanai child, son to my eighty-eight year old mother, brother to my sister, and a contributing member of my church and my community.

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran served two terms in the State House (2009–2012) and is in his second term in the State Senate (2013–present). He will be Vice Chair of the Senate Ways and Means Committee in 2018. He previously served as chair of the House Judiciary Committee and the Senate Judiciary and Labor Committee.