The Cayetano Legacy

A Governor Ben Cayetano Retrospective

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran and Alfredo G. Evangelista

Editor’s Note: 2019 marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the election of Benjamin J. Cayetano. This is the twelfth and final in a series of columns profiling Cayetano and his historic election and service.

The First of His Name

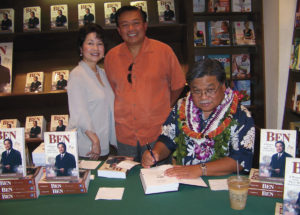

Image courtesy Ben Cayetano

Benjamin Jerome Cayetano was our Governor. He just happened to also be the first Filipino-American elected as Governor, not just of Hawai‘i, but any American state. We knew “Uncle Ben” way before he became Governor Cayetano.

It’s always difficult to be the first. Hawai‘i was admitted to the union just sixty years ago. In a young state, trailblazing can be even more daunting because the first is simply living history. Without an absolute majority from any one ethnic or racial group, every Governor inevitably becomes a first—the first American of Japanese Ancestry, the first Native Hawaiian, the first woman, the first Jew, the first confirmed Episcopalian, the first Okinawan. Guv, the initial Filipino to hold the office, fairly or unfairly, sets the initial standard and leaves an impression about the kind of leadership to be provided by his ethnic segment of the community.

Living up to the expectations of an entire ethnic bloc should be unnerving. But Guv simply made the hard calls and moved forward. “Let the historians judge me,” he more than once said in dismissal of too much political introspection by his cronies. At another time, he advised some of his younger political appointees, “Do your jobs. Let me worry about the politics.” In fact, although Ben as Governor served as the titular head of the local Democratic Party, he resisted requiring the active participation of his political appointees in partisan activities.

During the eight years, Ben never dictated any decisions at the departments where we served. He disagreed at times with certain results, explaining forcefully his reasoning in often blunt and colorful fashion. But he accepted the decisions and the rationales.

Winter Is Coming

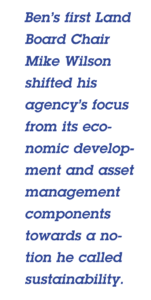

Photo: Alfredo Evangelista

When Lt. Governor Cayetano launched his campaign for Governor, he was an underdog. Confident that he would be a good steward of the State, he chafed at early polls that downplayed his candidacy. Eight years as second banana to the charismatic John Waihe‘e had lowered his profile below his likely opponents Honolulu Mayor Frank Fasi from the Best Party and U.S. Congresswoman Pat Saiki from the GOP, and in some circles, even his Democratic Party primary opponent Health Director Jack Lewin. As a legislator, Cayetano had been a reliably quotable, if not somewhat acerbic critic of various Governors and their directors, and even City Prosecutor Chuck Marsland. The flamboyant, blunt-talking local Filipino trial lawyer made colorful copy.

When he took office as Hawai‘i’s fifth post-Statehood Governor, the Kalihi native and Farrington High School graduate faced a drastic economic slowdown. Previous Governors had reaped the benefit from the rapid growth stimulated by the post-World War II jet-age, expanding tourism in a more egalitarian manner and stirring investment and construction in new infrastructure, homes and visitor accommodations. He would also see the continuing closure of the ubiquitous plantations that once made Sugar and agriculture generally the commercial King in the islands.

In predictable accounts of his administration, his accomplishments in spite of tough financial time dominates memories of his term. As his close and longtime associate Earl Anzai, who would serve as his Budget director and then Attorney General recalls, wrestling the state budget shortfall immediately upon taking office dogged his first years.

The Bells

While criticisms from his long-time supporters—teachers and public worker unions—had to bother Ben, Anzai rejects the budget cutting as a betrayal: “Don’t forget that Governor Cayetano also spared DOE from cuts. As you know it is the single largest component of state spending.” While DOE did see millions shaved from its operating budget, other departments lost much more—some seeing double-digit percentage cuts in general tax revenue support for their programs and worker costs.

Photo courtesy Alfredo Evangelista

In Anzai’s view, Guv forthrightly accepted that the revenue downturn blocked maintaining the same budget path and shelved many changes that Ben urgently wanted. Ambitious new programs and expansion on Ariyoshi-planned and Waihe‘e-era initiatives—things that Cayetano had campaigned on—could not be pursued. Those ideas, Anzai ruefully summarized, were reduced to wishful thinking. “You can imagine how upset Ben was,” he recalls.

Governor Cayetano made courageous but difficult decisions to tame the state budget deficit. He did so with due regard for how the first reduction in force of government workers would sour the public worker unions to his party. Despite the disparagement of the education budget reductions, his Comptrollers at the Department of Accounting and General Services oversaw construction of sixteen new schools—more than any prior period in Hawai‘i’s history. While educator disaffection would hamper efforts by his Lt. Governor Mazie Hirono to succeed him, Cayetano did provide significant pay raises for teachers—shifting starting salaries from $25,000 to $34,300 or a 34% increase over the course of five years. Cayetano’s collective bargaining office negotiated a teachers’ contract that included salary incentives for professional development. During his Administration, Cayetano launched the state’s first charter schools, implemented an electronic school, reached substantial compliance with the Felix Consent Decree, and started the Pre-Plus Program.

Stormborn

Crisis, in Asian culture, also offers opportunities and the Cayetano years allowed a re-examination of how the relatively new Hawai‘i state government approached crucial areas. While for certain specific initiatives the new Governor took direct control, Cayetano’s management philosophy encouraged his department directors to use the budget challenge as an opportunity to re-make their areas. Technology. Changing philosophies. All were on the table.

Ben’s first Land Board Chair Mike Wilson shifted his agency’s focus from its economic development and asset management components towards a notion he called “sustainability.” While no one would accuse Ben of being an environmentalist, his eight years included preserving the 304-acre Ka Iwi coastline, protecting the spawning habitats of bottomfish, acquiring a permanent home for the State Foundation on Culture and Arts, and fostering a Department of Land and Natural Resources with sustainability as its governing principle. The changes also spurred reassessment of the leasing and concession programs for public lands and boating facilities—whether fair market rentals should be required on all leases, regardless of historical and other concerns. One of the more surprising results was Ben signing off on establishing the Hawaiian Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary—federal officials and quite a few DLNR and Office of Planning employees expected Ben to reject the proposal that had been in the works throughout the Waihe‘e Administration. But while confident in his own ability to analyze issues, Governor Cayetano really did listen to those with expertise in many areas before exercising his own independent judgment. Approving the sanctuary was one of them.

Ben’s first Land Board Chair Mike Wilson shifted his agency’s focus from its economic development and asset management components towards a notion he called “sustainability.” While no one would accuse Ben of being an environmentalist, his eight years included preserving the 304-acre Ka Iwi coastline, protecting the spawning habitats of bottomfish, acquiring a permanent home for the State Foundation on Culture and Arts, and fostering a Department of Land and Natural Resources with sustainability as its governing principle. The changes also spurred reassessment of the leasing and concession programs for public lands and boating facilities—whether fair market rentals should be required on all leases, regardless of historical and other concerns. One of the more surprising results was Ben signing off on establishing the Hawaiian Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary—federal officials and quite a few DLNR and Office of Planning employees expected Ben to reject the proposal that had been in the works throughout the Waihe‘e Administration. But while confident in his own ability to analyze issues, Governor Cayetano really did listen to those with expertise in many areas before exercising his own independent judgment. Approving the sanctuary was one of them.

Image courtesy Alfredo Evangelista

Ben’s Department of Commerce and Consumer Affairs (“DCCA”) Director Kathryn Matayoshi also took the initiative to spur modernization efforts, including weaning DCCA operations off any General Fund subsidies. She would push her managers to put more services online and to improve the efficiency of processing regulatory licensing with technological investments. Working with the legislature, Matayoshi successfully created the Compliance Resolution Fund which collected and dedicated all fees charged by DCCA for the department’s operations. Ben approved her approach and allowed Kathy to run with the ball.

The Breaker of Chains

Photo courtesy Joseph Blanco

Cayetano’s Economic Revitalization Task Force (“ERTF”), which included a cross-section of influential local leaders in Hawai‘i’s financial, development, business and governmental sectors, and private and public organized labor, proposed a package of legislative and regulatory changes to spur the economy, including reconfiguring various aspects of how Hawai‘i’s government operated.

For the University of Hawai‘i (“UH”), the ERTF aimed at long-sought independence from legislative and executive oversight. While Cayetano supported UH President Kenneth Mortimer’s proposal to expand autonomy, the budget reductions to higher education battered Ben with often scathing criticism from faculty members and students. Anzai and the others on the financial team were surprised but not very shocked by the strong reaction from Mānoa’s Ivory Tower. Surely, the faculty should have understood the fiscal crisis facing the State. But the bean-counters also realized all the public worker unions—the faculty was no exception—observing the growth in the economy that followed Statehood through the end of the Burns Administration, most of the Ariyoshi years, and in the confident Waihe‘e tenure, remained rightly focused on negotiating additional pay raises and improved benefits for their members.

Cayetano executive assistant Joseph Blanco, who served two terms on the UH Board of Regents, recounts, “Governor Cayetano used the power of his office to give the University of Hawai‘i Constitutional Autonomy. The governor secured support from two-thirds of the legislature to pass a constitutional amendment and then ensured that ballot initiative passed with overwhelming public support … one of the most significant milestones in the history of the University of Hawai‘i.”

Photo courtesy Lance Collins

Act 115 (1998) weaned UH leaders from oversight by the state and capped President Mortimer’s efforts to win the university system more control over its affairs. The University Board of Regents would be charged with determining fees without going through the process required for all other State agencies. The administration also proposed tuition increases and more emphasis on student loans. At the time, Hawai‘i students enjoyed some of the lowest tuition rates in the country. Lance Collins, a part-Filipino lawyer who was raised on Maui, recalls student leaders swiftly reacted and organized statewide protests against the tuition increases. And they blamed Ben even though the university president was not an official member of the Administration or Cabinet. “Some of that was probably deserved but Cayetano became the scapegoat for what was really a complex set of decisions by University administrators, the legislators and the Governor in reworking the University’s relationship to the state treasury,” Collins explains.

Collins, in retrospect, believes Cayetano “was the first Governor who didn’t just give the University administration or faculty a pass with its funding requests.” In Collins’ reassessment, Ben’s approach required the university and its constituencies to “more carefully and honestly justify its use of taxpayer money.” But while the university administration received more responsibility (and the long-sought autonomy in spending), like other agencies now tasked with managing large budget cuts, Collins thinks UH’s leadership “floundered in many respects.” Collins points out that the University prioritized “flashy academic units” over ones with broad-based community impacts. He describes the School of Medicine cannibalizing the School of Public Health. During Cayetano’s Administration, the university broke ground for the new $300 million John A. Burns School of Medicine and Biotech Center on State land in Kaka‘ako, and Cayetano approved investing more than half a billion dollars in upgrading UH facilities, and developing the new Institute for Biogenesis Research. Cayetano also directed his office to pursue luring institutions like the Mayo Clinic or M.D. Anderson and others to consider Hawai‘i as an outpost.

The Watchers on the Wall

Photo courtesy Alfredo Evangelista

The common belief that State spending is a zero-sum calculation—like a family’s checking account—somewhat overly simplifies the limitations legally imposed on government budgeting. Hawai‘i law and sometimes federal law, however, statutorily circumscribed certain taxes and fees for specified uses. For example, while the Department of Transportation is allocated tremendous sums for projects at Hawai‘i’s airports, harbors and highways, those projects are paid from revenues and fees generated by airline landing fees and airport concessions, harbor fees and gas taxes that federal requirements legally allow solely for transportation-related facility improvements. The problem with the State budget was a shortfall in revenues collected from general tax sources—income taxes, general excise taxes and other sources that were not specifically earmarked for particular purposes.

While Collins recognizes the timing of Cayetano’s tenure with the economic downturn of the 1990s (the end of the overseas investment bubble), he remains critical that the cuts to the university budget went into funding creation of the Hawai‘i Tourism Authority (“HTA”) instead. Given the expanding role of tourism in the State’s economy, the ERTF agreed on the need to address “the level and uncertainty of funding for tourism marketing and promotion.” The aftermath of the first Gulf War and recovery from the hurricane that hit the island of Kaua‘i, contributed to the State’s difficulty in recapturing the rapid post-World War II economic growth. While the Holy Grail of diversification of the local economy could not be ignored, given the Visitor Industry’s increasing importance, the ERTF believed “tourism is also where positive changes are likely to have the largest effects.”

While Collins recognizes the timing of Cayetano’s tenure with the economic downturn of the 1990s (the end of the overseas investment bubble), he remains critical that the cuts to the university budget went into funding creation of the Hawai‘i Tourism Authority (“HTA”) instead. Given the expanding role of tourism in the State’s economy, the ERTF agreed on the need to address “the level and uncertainty of funding for tourism marketing and promotion.” The aftermath of the first Gulf War and recovery from the hurricane that hit the island of Kaua‘i, contributed to the State’s difficulty in recapturing the rapid post-World War II economic growth. While the Holy Grail of diversification of the local economy could not be ignored, given the Visitor Industry’s increasing importance, the ERTF believed “tourism is also where positive changes are likely to have the largest effects.”

Cayetano economic development official Brad Mossman points to the HTA as the most enduring result from the ERTF efforts but likely doesn’t draw any linkage between cuts at the university with that creation. The dedication of hotel room tax revenues provided resources that improved promotion, based on more research and data on markets. The changes also rationalized convention center payments. Under existing conditions, when East Coast visitors dropped off, the different island visitor bureaus, hotels, and visitor-dependent businesses did not have the ability to coordinate efforts to make up for the losses. The HTA was also structured to have broader representation of the visitor industry than just the Waikīkī hotel leaders, ensuring neighbor island seats. The hike to the TAT rate also spared the Counties from annually lobbying the State for grants by allocating a dedicated portion of the hotel room taxes for their use as well.

Cayetano’s administration completed the $350 million Convention Center outside of Waikīkī “on time and on budget” and his office helped attract and host the Miss Universe Pageant (on the heels of Hawai‘i-native Brook Lee completing her reign), the Asian Development Bank convention, and other meetings.

And Now His Watch is Ended

Photo courtesy Alfredo Evangelista

But a total assessment of his record comes down to the impacts on a person’s own life from his decisions and the perception established about Cayetano from various opinion makers. To many of his long-time associates, the press was not very kind to Cayetano as Governor.

His supporters complained Ben did not get the credit for the good things he accomplished. Guv worked with the legislature and the private sector, to pass the largest tax cuts in Hawai‘i history, saving taxpayers about $2 billion over six years. In tough negotiations with longtime allies in the public sector unions, he passed legislative changes that reduced the annual growth of government and launched civil service reform, including setting the stage for some privatization of government services. He set the stage for addressing one of the cost-drivers for the State’s unfunded liability by reforming the State Health Fund—consolidating all current workers and retirees into one Employer Union Trust Fund to manage medical benefits for public workers. Governor Cayetano approved creating a “Rainy Day Fund” for future budget challenges. His administration worked to reduce prescription drug costs and to provide better oversight over insurance rates, and reduced workers compensation insurance costs for Hawai‘i’s businesses. The Cayetano Administration also developed a record number of affordable rental housing units—more than all prior governors combined.

Building on national requirements, his Department of Human Services helped welfare recipients to transition to the workforce. He started the effort to require treatment programs for first time drug offenders. He explored with the legislature ways to cap gasoline prices. In order to prime the construction sector, he introduced a $1 billion capital improvements program which kept Hawai‘i’s building industry afloat. The Cayetano administration worked with the legislature to encourage high technology and biotechnology growth in Hawai‘i. Ironically, he also intervened to stave off an initial attempt to close the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, the more conservative of the two O‘ahu dailies and a critic of his administration. As happened in other states, the two dailies would later merge after the end of his term.

For some, one of the biggest changes during his tenure resulted from the work of his Attorney General Margery Bronster in cleaning up the operations of the Bishop Estate and the selection and compensation of trustees for all local trusts.

In issues important to the Filipino community, Ben released $1.5 million dollars for the Filipino Community Center in Waipahu and $1 million dollars for Maui’s Filipino community center, and appointed members to the Commission on the Celebration of the 100th Anniversary of the Arrival of the Sakadas in Hawai‘i. Gov. also appointed the largest number of Manongs and Manangs to positions in state government.

The Rains of Castamere

Photo courtesy Alfredo Evangelista

As Governor, Ben perhaps did not appreciate at first how his every pronouncement now had impacts that his quips and barbs as a State Rep., Senator and even Lt. Governor did not. While people may suggest they want their elected officials to talk to them in a straightforward and honest manner, politicians can never please everyone. Since entering public life, Cayetano never held back his opinions when he believed government leaders, including fellow Democrats, were “playing politics” instead of serving the public.

That certainty in his own assessment of the best course made Cayetano an easy target for everyone, including the political pundits, the media, other elected officials, and the person on the street who differed with his position or, often, how he expressed that view.

But even members of the local Filipino community, the Filipino media included, had no qualms in quickly complaining about and chiding the Governor.

Some of his closest associates, and undoubtedly the Governor himself in retrospect, granted that some criticisms may have been well-founded. But they all still concluded that Governor Cayetano was the right person for the job at the time—making some tough choices against his own social policy inclinations.

Unbowed, Unbent, Unbroken

Photo: Alfredo Evangelista

In 1998, Ben wrote of his hopes: “The Hawai‘i I would like to leave to my children and to my children’s children is one in which the economy will be diverse and dynamic; the environment will be pristine; and our quality of life continues to be among the highest in the world. And perhaps most importantly, our Aloha Spirit will continue as the bond that holds everyone together … We must take great care to foster the Aloha Spirit because it is important to our character as a community and as a state in a global society. It is the spirit that moves us to help our neighbors and to welcome visitors to our home with a warm and bountiful hospitality.”

The Aloha Spirit described by Governor Cayetano combines the Bayanihan spirit and the all-encompassing Mabuhay in Filipino culture.

Collins also concludes, “For the Filipino community, in my view, his position as a two-term governor helped soften the otherwise harsh unconscious and/or conscious racism held by many people about the abilities of Filipinos in Hawai‘i.”

After returning from the mainland to practice law in Hawai‘i, Cayetano dedicated a substantial portion of his working life to public service: several years as a Housing Authority member, four years in the State House, eight years in the State Senate, eight years as Lt. Governor and eight years as Governor. As Governor, he was dedicated to serving the best interests of the people of the State of Hawai‘i and sought Cabinet members with similar dedication. During his time in office, Governor Cayetano served without any major blemish on his personal reputation.

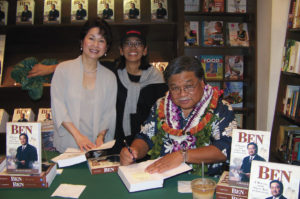

Whatever tough decisions he made during his eight years as Governor, the best assessment of his tenure is captured at the end of his autobiography, Ben: A Memoir, From Street Kid to Governor:

“When I began my political career in 1974 I was a 34-year-old lawyer full of idealism, ready to change the world. A veteran legislator who took a liking to me took me aside and offered the following: ‘Ben,’ he said, ‘you remind me of myself when I first got into politics. I was a reformer; I wanted to change the world. You’re no different. But after being in this business for 20 years now, I think the best any politician can hope for before he leaves is that he helped to make life a little better for our people.’

‘He was right.’”

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran and Alfredo G. Evangelista practice law in Wailuku, Maui. They worked on Ben Cayetano’s campaigns for Governor and Lt. Governor and served in various appointed positions during the eight years of the Cayetano Administration (1995–2002). At some point, however, they dropped their familiarity and “Uncle Ben” became “Governor Cayetano” or “Guv”. Except for quotes from other people, this column represents their own views. Portions of this column, in slightly different form, previously appeared in the program for an event honoring Governor Cayetano at the end of his term organized by Hawai‘i’s Filipino community.