Judge Alfred Laureta’s life and legacy honors our shared Filipino ancestry and community.

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran

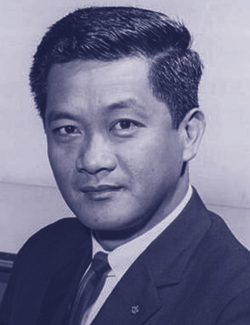

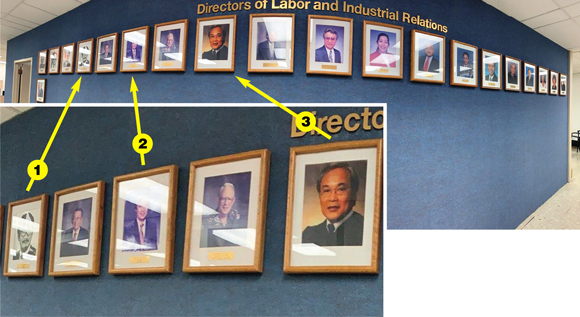

Photographs of past Directors of the State of Hawai‘i Department of Labor and Industrial Relations line the walls of a conference room at the Princess Ruth Ke‘elikōlani building in Honolulu. One includes a strikingly handsome young lawyer named Alfred Laureta. While that room is not readily open to the public, it’s a suitable memorial for Laureta, a Hawai‘i Filipino pioneer remembered as humble, amiable and down to earth. For many, Laureta also remains an inspirational example of early Statehood leaders, even as he himself attributed so much of his individual accomplishments to community support.

Photo: Hawai‘i State Archives

Small kid time, emcees at Filipino events often recognized prominent members of the Maui community in attendance. Local Pinoys got an added boost by describing them as “the first Filpino” to serve as such-and-such or appointed to this or that. For example, Richard Caldito was the first Filipino County Councilman in the U.S., Jose Romero was the first Filipino doctor on the island or Claro R. Capili, Sr. served as the first acting Mayor of Filipino ancestry.

The young man born in 1924 at what was called Banana Camp on O‘ahu’s Ewa plains could not have envisioned the many firsts he would earn on the state and federal levels. In fact, when Governor Jack Burns appointed Laureta in 1963 as Labor Director, Al won the distinction of being the first Filipino-American appointed to a Gubernatorial Cabinet level position anywhere in the United States. Laureta’s appointment blazed the trail for, in former Governor Ben Cayetano’s view, “guys like him”—local-born children of workers from Asia, the Azores and other places recruited to work in Hawai‘i’s sugar and pineapple plantations. Hawai‘i Governors—Burns, Ariyoshi and Cayetano—would later add other talented Filipino directors like Joshua Agsalud, Mario Ramil and Leonard Agor to that conference room wall.

Photo: Anne Perreira Eustaquio

When Al Laureta graduated from Lahainaluna High School in the early 1940s, Hawai‘i was entering a great transitional period in the midst of a global war. The only child of immigrant Filipino parents with little formal education, Laureta’s academic prowess got him notoriety. His parents divorced when he was young and he would be raised by his dad among the “single men” in Maui’s plantation camps and went to Makawao Elementary. Known for his good humor, Laureta always had a good story. As Kaua‘i’s The Garden Island news noted in a 2019 profile, Laureta recounted at his first judicial appointment in 1967, the role of his father’s co-workers: “The single men looked on me as their responsibility, encouraging me to do well in school … My report card became community property.”

Laureta would be one of the few Filipino students at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa which reflected the reality of the time. Most island Filipinos came from the plantations and were hard-pressed to afford higher education for their children. Al would work his way through UH, earning tuition with the “good money” made at summer Pineapple Cannery jobs.

Laureta, like many in the generation that came of age after World War II, came to understand education was key to elevating the socio-economic status of his ethnic community and other groups from the plantation. While he earned an education degree in 1947, Laureta wanted to go to law school. In The Garden Island profile, Laureta recalled, “At that time in the history of Hawai‘i, there were no professional Filipinos in any kind of business.” Professions, he thought, generally required getting a mainland graduate degree.

Laureta recalls a priest named Osmundo Calip took an interest in his dreams and convinced prestigious Fordham University Law School to enroll him. (Calip was a former Philippine army chaplain who would organize a statewide network of Filipino Catholic clubs.) Laureta also noted among the groups providing him with support was a local Japanese organization that previously awarded Hawai‘i Americans of Japanese Ancestry (AJAs). The group decided to help him as they were aiding other Hawai‘i students. He promised them he would return to practice law in Hawai‘i. With a three-year scholarship, Laureta would move to the Bronx and receive his Juris Doctor in 1953.

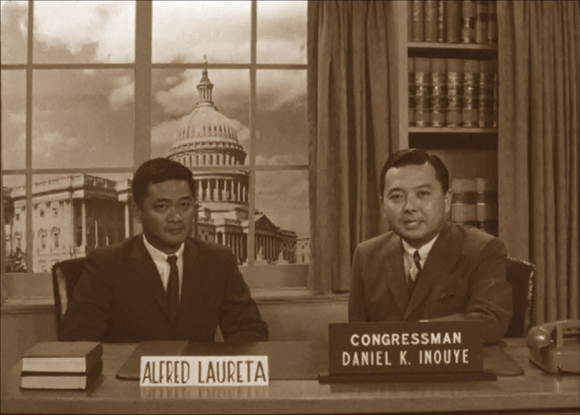

Photo: ‘Ulu‘ulu Moving Image Archive and the Daniel K. Inouye Institute

He also met his wife Evelyn Reantillo, a nursing student, during his time on the East Coast. She would support their young family when they fulfilled his commitment and moved back to Hawai‘i. Without a job and expecting a first child, Laureta studied for the bar exam and in 1954 became only the third Filipino admitted to practice law at that time.

Laureta, trying to develop a law practice, would be drawn into the groundwork organizing for social changes in the post-War islands. His early law partners included Bert Kobayashi, later a Hawai‘i Supreme Court Justice and Russell Kono, who would serve as a district court judge. He would become a law partner of a young Nisei veteran named Daniel K. Inouye and another AJA named George Ariyoshi. He would be recruited into their Democratic Party organizing activities with a local haole police officer named John Burns.

Laureta, trying to develop a law practice, would be drawn into the groundwork organizing for social changes in the post-War islands. His early law partners included Bert Kobayashi, later a Hawai‘i Supreme Court Justice and Russell Kono, who would serve as a district court judge. He would become a law partner of a young Nisei veteran named Daniel K. Inouye and another AJA named George Ariyoshi. He would be recruited into their Democratic Party organizing activities with a local haole police officer named John Burns.

Following the Democratic election “revolution” in 1954, Laureta would serve the new Democratic majority in the Territorial House of Representatives as House attorney with fellow young lawyers Patsy Mink who would later serve as Congresswoman and Herman Lum who later became Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Hawai‘i. In 1959, Laureta would serve as an administrative assistant in the U.S. Congress when his partner Danny Inouye was elected as the new State of Hawai‘i’s first U.S. Congressman.

Governor Burns would call Laureta back from Washington, D.C. to the islands to serve in his Cabinet. Upon confirmation, the child of a Filipino plantation worker became head of the State Department of Labor and Industrial Relations.

A few years later, Burns appointed Laureta as the first Filipino-American State court judge in 1967. Laureta would serve on O‘ahu’s first circuit court before transferring to Kaua‘i’s fifth circuit court in 1969.

In 1977, an Act of Congress established the Territory of the Northern Marianas. In 1978, President Jimmy Carter made Laureta the first federal Judge of Filipino descent nationally. Upon U.S. Senate confirmation, Laureta became the first judge for the newly-established U.S. District Court for the Northern Mariana Islands (Saipan), serving from 1978 to 1988.

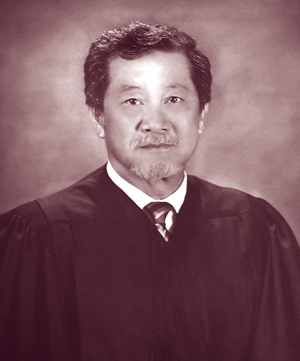

Photo: Hawai‘i State Bar Association

As he recounted to the Honolulu Advertiser when appointed, “There’s no federal court building in Saipan. Court will initially be held in the lounge of the Saipan Continental Hotel, at one time a small gambling casino when slot machines were legal on the islands.”

Laureta retired to Kaua‘i where he continued to participate in the community—volunteering with Kaua‘i Economic Opportunity as a mediator, serving as the Kaua‘i commissioner on the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts and as an elected director on the Kaua‘i Island Utility Cooperative, among other activities.

Laureta passed away on November 16, 2020 at his home on Kaua‘i, surrounded by his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. In a StarAdvertiser obituary, one of his former law clerks Robin Campaniano provided the following coda: “He taught me how to be a lawyer and how to be very judicial. He showed me judicial temperament and how that should permeate everybody’s life: How to be honest, fair, to be a person with integrity and to be humble at the same time.”

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran practices law in Wailuku and represents Central Maui in the State Senate. He spent only three months as Director of Labor during Governor Ben Cayetano’s administration but has a photo on the wall in the same conference room as Judge Laureta.

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran practices law in Wailuku and represents Central Maui in the State Senate. He spent only three months as Director of Labor during Governor Ben Cayetano’s administration but has a photo on the wall in the same conference room as Judge Laureta.