Cultural Connections

Relationships are deeper than commonly thought. The CD release of Kāwili starts new conversations raising questions about being one ‘ohana.

Alfredo G. Evangelista | Assistant Editor

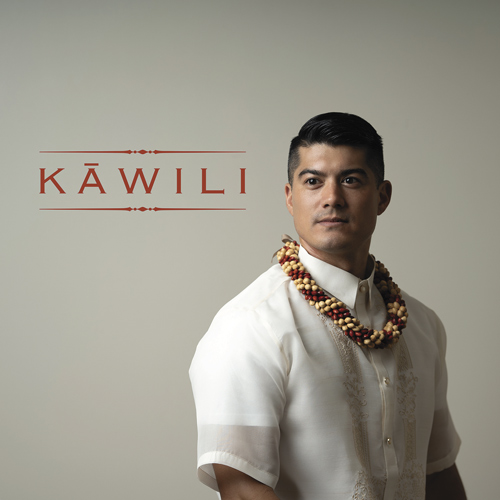

A couple months ago, a I received a complimentary copy of the Kawili CD sent by Lance Collins, Ph.D., a Maui attorney who was a co-producer of the album. I hadn’t purchased it through my Amazon Business Prime account and there was no invoice attached so I figured it was free—free is free, they say—and left it on the side.

Image courtesy Lance D. Collins

But the buzz surrounding the release of Kawili started to increase and because my car no longer has a CD player (neither does my lap top), I had to find an external CD player. As the first song, Tinikling played (as it is playing while I write this), I enjoyed the medium speed that I could probably dance to (yeah, right my wife Bessy says) (step in, step out, hop or something like that).

When the CD played the second song, Leron, Leron ‘eā, I recognized the tune as Leron Leron Sinta, which as a youngster our Good Shepherd Church Filipino Youth Choir sang under the direction of Manang Nancy Andres. But the lyrics were not what I learned and I realized they were in Hawaiian! Oh wow! I started to read the CD cover and the inserts:

“Hawaiians and Filipinos are connected throughout history by genealogy and cultural practice. In the modern period, Hawaiians and Filipinos first encountered one another at the margins of the historical record—such as chief Ka‘iana’s visit to Zamboanga—until the American period, when a coordinated effort by sugar plantations brought many Filipinos to Hawai‘i as contract laborers. Although Filipinos and Hawaiians, by and large were members of the working classes, the encounter was structured and circumscribed by the plantations’ policy of racial hierarchies and settler colonial logics that pervaded society at the time.”

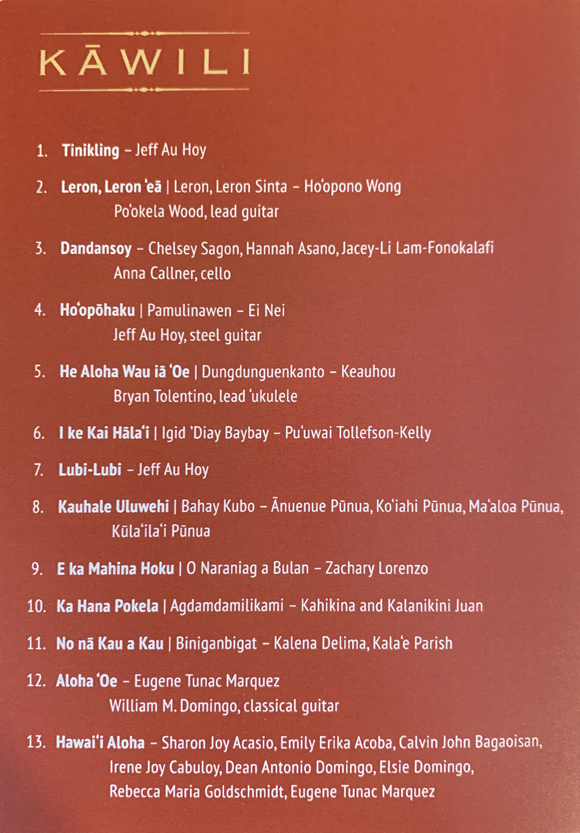

There are two definitions provided of kawili in the notes. The first definition is by M. Pukui and S. Elbert: “the act of mixing, blending, ensnaring of birds, entwining, interweaving” while the second definition is by L. English: “an amusement or an entertainment.”

I certainly recognized several of the Ilokano medleys—Pamulinawen, Dungdunguenkanto, Igid Diay Baybay and O Naraniang a Bulan. Of course, Lubi Lubi was instantly recognized as that was the song Mrs. Aggie Cabebe used as a warm up for our folk dance practices. Clearly, the CD was meant to be more than a fundraiser for the Refugee & Immigration Law Clinic at the William S. Richardson School of Law and the Ilokano Language and Literature Program at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. There was more to it than just money; there was a need to explore the cultural connections between Hawai‘i and the Philippines, through music.

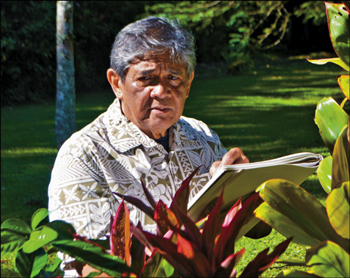

Photo courtesy Lance D. Collins

“One of the main ways the plantations historically pitted workers against each other was by using racial hierarchies and by erasing history,” explained Collins. “When workers of different races and ethnicities were able to unite, they increased their ability to demand fair pay for their labor. Similarly, by learning more about history, we are able to better understand our position in the present. The album seeks to do these things from the position and feeling of music.”

Maui’s Filipino community has a rich history with plantation workers—the Sakadas who first arrived in Hawai‘i on December 20, 1906—one hundred and fourteen years ago. The Binhi at Ani Filipino Community Center in Kahului even has a Sakada Wall that lists all the 1946 Sakadas who arrived on Maui, a list provided by the Hawai‘i Sugar Plantation Association which is full of mistakes but that’s how history is written.

When the 100th anniversary of the Sakadas was celebrated in 2006, historians noted the 1906 Sakadas were not the first Filipinos in Hawai‘i, explaining there were Filipinos who were part of the Royal Hawaiian Band who probably jumped ship from one of the trading ships and these Filipinos were known as Manila men of the Manila Galleons.

The notes to Kāwili shares an important cross-cultural fact involving a prominent member of the Royal Hawaiian Band: “Jose Sabas Libornio Ibarra, born in Sta. Ana, Manila, was a member of the Royal Hawaiian Band at the time of the overthrow of HM Queen Lili‘uokalani. With his bandmates, they refused to take an oath of loyalty to the provisional government and inspired Ellen Prendergast to compose ‘Mele ‘Ai Pohaku,’ known today as ‘Kaulana Nā Pua.’ Libornio composed the melody for the song. He led the reconstituted Hawaiian National Band and left for the United States to advocate for the restoration of the Kingdom. He eventually moved to Peru where he was appointed the director of Peru’s Army Band and subsequently composed the Peruvian National March.”

In Filipino-American Nationial Historical Society terms, Ibarra would be known as a disrupter—and made history along the way. He should definitely be on the list of Filipinos to be honored during Filipino-American History Month each October.

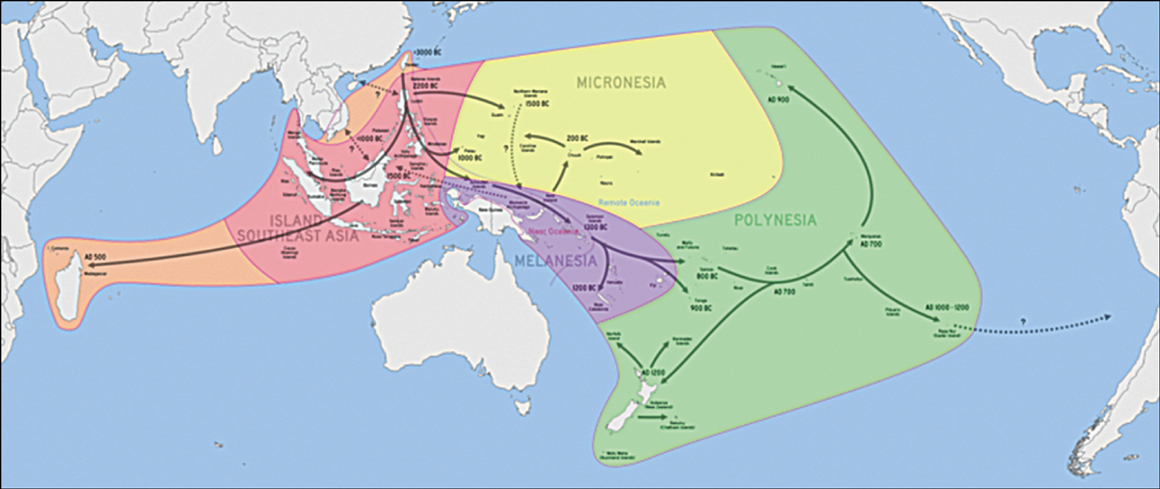

Image: Per Benton et al, 2012, adapted from Bellwood, 2011

I always scoffed when the historical notes to the Sakada Anniversary celebration commented there were several Filipino members of the Royal Hawaiian Band. As a proud son of a 1946 Sakada, I wanted the focus to be on those who left the Philippines to work in the plantations for meager wages. When my Dad Elias arrived on April 26, 1946, he earned 89.5 cents an hour cutting wood and later as a dairy barn milker. I did quite a bit of research about the Sakadas but never dealt deeply into the Manila Galleons; I was a political science major not a history major like State Senator Gilbert Keith-Agaran.

On December 20, 2020 (yes, Sakada Day in the State of Hawai‘i as designated by Hawai‘i law), however, my interest in the Manila Galleons trade (1565–1815) was spurred when Binhi at Ani was holding a brief dedication ceremony of its newly renovated kitchen. Due to the presence of iwi behind the physical structure, I requested Nora Cabanilla-Takushi, past president of Binhi to invite a Kahu to bless the renovated kitchen and the entire Center. When Kahu Wilmont Kahaiali‘i (yes, Willie K’s younger brother) arrived, not only did we receive a blessing but also a history lesson that touched on the Manila Galleons trade.

Kahu Kahaiali‘i spoke of the long-time connections between the Philippines and Hawai‘i through the Manila Galleons and shared the belief two ships—the San Jaunillo and the Santo Christo—were wrecked near Hawai‘i: “So the Spanish that were traveling from Mexico to the Philippines—two ships shipwrecked over here—the lead ship made it all the way. So we related to the Philippines by Spanish blood. And of course we like to say it was an accident that they ended up here but it was no accident.”

Kahaiali‘i, who is also an educator (teaching a variety of classes that you can check on his FB page: Wilmont Kaumanu Kahaiali‘i) and author (The Little Heroes who did BIG Things!), explained his grandmother was Spanish-Hawaiian. “I tell a lot of my Filipino ‘ohana and friends ‘Hey, you guys don’t know it but we family, that’s why Filipinos and Hawaiians, we tight.’”

Some historians even believe the connections between Filipinos and Hawaiians go even further than the Manila Galleons trade, the Royal Hawaiian Band, and the Sakadas. If a Filipino did a genealogy test through Ancestry.com as reknown artist Philip Sabado did a few years ago, you might be classified as Polynesian. (A few years ago, I was gifted a 23AndMe genealogy test by my then future-daughter in law Carolyn and learned I had roots to Africa.)

Photo courtesy Phil Sabado

Sabado did some studying about his Polynesian roots and learned about the Austronesian people and their connections with Polynesians. When he told me about it, being the skeptic I am, I kind of brushed it off—again, I was a political science major and not a history major!

But the Kāwili release, coupled with Kahu Kahaiali‘i’s brief historical reminder, got me interested. So I “googled” it and found quite a bit of information about the Lapita people, Austronesians, and stuff only archeologists could understand and relate to–and apparently some attorneys with a Ph.D. degree.

“A group of people from southwest China migrated to Taiwan about 10,000 years ago. They are called the Austronesians,” explains Collins, who presented a paper at the 2014 Philippines Studies Association Conference titled The Descendants: Theory, Nationalism and the Austronesian Diaspora. “They settled in the Philippines around 5,000 years ago and intermarried with the ‘Negrito’ populations. Population growth pushed some groups to move south and then west to what is today Malaysia and Indonesia. Others went east to what is today Micronesia. Still others migrated south and east through what is today Papua New Guinea. The Austronesians then began a second quick migration to Samoa and Tonga about 3,000 years ago and from there populated all of island Polynesia.”

Collins also explained how the comparison of languages helped to show the inter-relationship of people: “An 18th century Spanish linguist was the first to compare the languages of all these peoples and proposed that they were related as a family the way Indo-European is a language family. In the 19th century, a German linguist dubbed the peoples ‘Malay-Polynesian.’ Historical linguistics was able to create a theoretical family tree by the early twentieth century.”

If one researches (“googles”) more about the Austronesians, one will probably encounter some studies involving chickens, pigs and rats, which made me initially scoff at the theories. But Collins’ explanation puts it all in a different light: “Austronesian people purposefully took the pig and chicken wherever they went. They also brought along the Pacific rat—perhaps unintentionally. They took useful plants with them such as banana, sugar, coconut, breadfruit, taro, yam, sweet potato, noni, paper mulberry, kukui, mountain apple, turmeric, bamboo and medicinal plants among others. They also took with them technology and practices related to building, sailing, agriculture, tattooing and pottery. Common pottery making techniques were abandoned in Samoa and although absent in Polynesian cultures today, the traditional designs of the pottery have persisted.”

Yes, pottery. That added to my skepticism, confusion and unwillingness to accept any of these historical theories. But Collins, the resourceful and authoritative person that he is, had a great explanation: “It was not until after World War II with radio-carbon dating that archaeologists began to confirm what linguists and ethnologists had theorized for several hundred years. More recently, the use of genome sequencing and genetic testing has more precisely been able to confirm and demonstrate the movement of people out of Taiwan, into the Philippines, and then east, south and west across the Pacific and Indian oceans as far as Madagascar, Rapa Nui, New Zealand and Hawai‘i.”

Yup, genetic testing or in lawyer parlance, DNA testing. That same DNA testing that was made famous during the O.J. Simpson trial with The Dream Team led by Johnnie Cochran, is now key to exploring more connections between the cultures of Hawaiians and Filipinos.

Photos: Basilia I. Evangelista

Where the path leads to, who knows?

For the producers of Kawili, the next step is to take Hawaiian mele and “translate” it into Filipino medleys. Collins says it will take some time to complete the next project and the difficulties in producing Kāwili are not forgotten: “Because the album attempts to restage the encounter and relationship between Hawaiians and Filipinos different from how people present identify themselves and relate, there will naturally be resistance—because it is unfamiliar and novel. The process of picking songs, translating and arranging also took a lot of time, in part, to ensure that we were capturing the spirit of both worlds in a way that honored both as equal contributors.”

For Binhi at Ani, in connection with caring for the iwi, the Board of Directors is planning to have an annual Ho‘olaule‘a to celebrate the Hawaiian culture and recognize its importance as part of Binhi’s future.

Photo: Alfredo G. Evangelista

For me, one of the most interesting notes in the Kāwili CD was in reference to Aloha ‘Oe: “Aloha ‘Oe, composed by HM Queen Lili‘uokalani, is still performed at funerals in Ilocos–brought back by returning laborers of yesteryear.”

Aloha oe, aloha oe

Sapay koma agkita ta manen

Agnaedka, arakupenka

Sakbay pumanawak

And the words to Hawai‘i Aloha as translated in Ilokano now seem to have an even more deeper meaning:

O Hawai‘i a nangiyanak kaniak

Ti daga ken patubo a taengak

Iti gasat ti langit, rambakak

O Hawai‘i, Aloha-en.

Aragsak dagiti ubbig iti Hawai‘i

Agrambak! Agrambak!

Dagiti pul-oy a naalumamay

’Tay Aloha, para iti Hawai‘i

In our lifetime, we may never fully understand how really connected our cultures are. But one thing is true, We are all ‘ohana.

Photo: Lawrence M. Pascua

Alfredo G. Evangelista is a is a sole practitioner at Law Offices of Alfredo Evangelista, A Limited Liability Law Company, concentrating in estate planning, business start-up and consultation, nonprofit corporations, and litigation. He has been practicing law for 37 years (since 1983) and returned home in 2010 to be with his family and to marry his high school sweetheart, the former Basilia Tumacder Idica.

Alfredo G. Evangelista is a is a sole practitioner at Law Offices of Alfredo Evangelista, A Limited Liability Law Company, concentrating in estate planning, business start-up and consultation, nonprofit corporations, and litigation. He has been practicing law for 37 years (since 1983) and returned home in 2010 to be with his family and to marry his high school sweetheart, the former Basilia Tumacder Idica.

Evangelista is a graduate of Maui High School (1976, during the time when students were taught World Cultures instead of Hawaiian History), the University of Southern California (1980, majoring in Political Science), and the University of California at Los Angeles School of Law (1983).