Killings come to a head—gun laws re-examined.

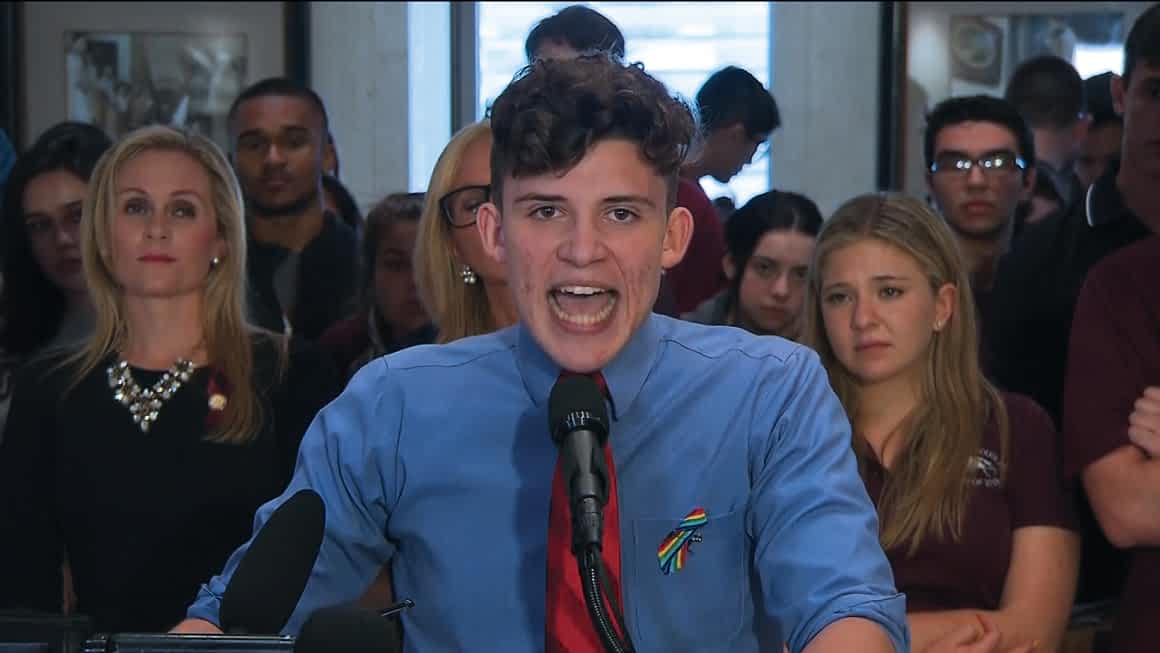

Photo courtesy cnn.com

On August 1, 1966, former Marine and university student, Charles Whitman fired down on passersby from the observation deck of the University of Texas at Austin clocktower. By the time police reached and killed him, seventeen were dead or dying and thirty-one others were wounded. The Texas Tower shooting in some assessments marks the first of modern American mass shootings.

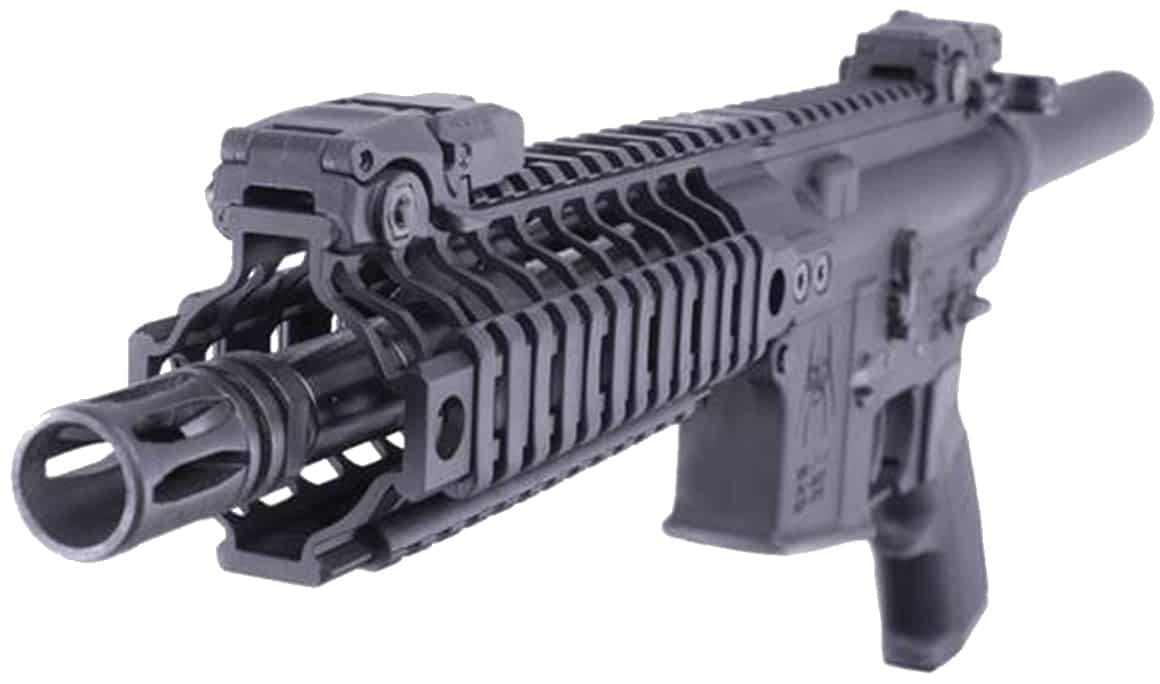

Photo courtesy cheaperthandirt.com

Gun-related killings in schools (University of Texas, Columbine High, Sandy Hook Elementary, Virginia Tech, Stoneman Douglas) and churches (Sutherland Springs) tend to stick in the public’s imagination but killings in those locations make up a relatively small portion of mass shootings. Shootings at offices (Edmond Post Office), restaurants (San Ysidro McDonald’s) and other commercial spaces (Las Vegas concert, Orlando nightclub, Aurora theater) occur more often.

Hawai‘i’s own entry in the grim list took place in the shooter’s workplace. On the morning of November 2, 1999, service technician Bryan Uyesugi brought a semi-automatic pistol to the Xerox Corporation building in Honolulu and shot and killed his supervisor and six co-workers, while wounding an eighth person. In August 2000, Uyesugi was convicted of first degree murder and sentenced to life without possibility of parole. The Uyesugi shooting remains the most infamous mass murder in modern State history. In 2001, the Hawai‘i Legislature passed Act 252, requiring health care providers to disclose health information to police for the purpose of evaluating a person’s fitness to acquire firearms.

Photos courtesy murderpedia.org

In the wake of mass shootings in recent months—at a Country Music festival in Las Vegas and at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida—measures to address mass gun violence are again under discussion in the U.S. Congress and in various State legislatures, including Hawai‘i. Since the 10-year federal ban on assault rifles expired in 2004, the AR-15, a lightweight, customizable version of the military’s M16 has become a popular purchase. Some of the Las Vegas shooter’s guns were fitted with legal devices called “bump-fire stocks,” which allow semiautomatic rifles like an AR-15 to fire as quickly as automatic ones. The Parkland, San Bernardino and Newtown shooters also used AR-15s during their rampages.

Since the expiration of the federal Assault Weapons Ban in 2004, America’s attention to gun control in recent proposals focus on a few specific measures: universal background checks, restrictions on people with mental illnesses buying firearms, and renewal of the assault weapons ban. American elected officials, even those who consider themselves liberals or progressives, rarely venture further. Australia, for example, in the wake of a 1996 mass shooting, adopted a law which amounted to a confiscation program. Australian lawmakers banned automatic and semiautomatic rifles and shotguns. The Australian government confiscated 650,000 of those type of guns through a gun buyback program. Australia also established a registry of all guns owned in the country and required a permit for all new firearm purchases. Harvard-based researchers note that Australia’s gun homicide rate dropped by about forty-two percent in the seven years after the law passed, and the country’s firearm suicide rate fell by 57 percent.

Since the expiration of the federal Assault Weapons Ban in 2004, America’s attention to gun control in recent proposals focus on a few specific measures: universal background checks, restrictions on people with mental illnesses buying firearms, and renewal of the assault weapons ban. American elected officials, even those who consider themselves liberals or progressives, rarely venture further. Australia, for example, in the wake of a 1996 mass shooting, adopted a law which amounted to a confiscation program. Australian lawmakers banned automatic and semiautomatic rifles and shotguns. The Australian government confiscated 650,000 of those type of guns through a gun buyback program. Australia also established a registry of all guns owned in the country and required a permit for all new firearm purchases. Harvard-based researchers note that Australia’s gun homicide rate dropped by about forty-two percent in the seven years after the law passed, and the country’s firearm suicide rate fell by 57 percent.

According to many tallies, Americans have the highest number of privately owned guns in the world. The Washington Post noted that 47% of Americans reported having a gun in their home in 2011. The United States has a somewhat unique gun culture that in some estimations is enshrined in the country’s constitution through the Second Amendment. After Sandy Hook, the Manchin-Toomey bill, the only proposal that came closest to being enacted, did not even require universal background checks.

According to many tallies, Americans have the highest number of privately owned guns in the world. The Washington Post noted that 47% of Americans reported having a gun in their home in 2011. The United States has a somewhat unique gun culture that in some estimations is enshrined in the country’s constitution through the Second Amendment. After Sandy Hook, the Manchin-Toomey bill, the only proposal that came closest to being enacted, did not even require universal background checks.

The U.S. Supreme Court and many federal and state lawmakers widely acknowledge that the Second Amendment does place limits on how far gun restrictions can go. As a result, anything like the Australian policy response is unlikely short of a court reinterpretation of the Second Amendment’s protection of individual gun rights, or a repeal of the Second Amendment.

While the Parkland school shooting has resulted in some businesses distancing themselves from the NRA, little legislation has passed in State legislatures and Congressional leadership has not scheduled any votes on proposed gun bills, including an assault weapons ban and stricter background checks. In fact, a moratorium on the sale of AR-15 and stricter background checks were recently rejected by the Florida legislature despite the lobbying of survivors of the Parkland killings.

In Hawai‘i, a proposal to specifically ban bump stocks is moving through the Legislature. Hawai‘i presently has some of the strictest firearms laws in the country. Unlike the lower-forty-eight states where firearms law vary widely by jurisdictions and where gun owners can move freely across state and county lines, movement to the islands from another State generally requires an airline flight where firearm transportation is regulated.

In recent years, the Hawai‘i Legislature has expanded categories that disqualify a person from owning and possessing firearms, including adding domestic violence-related misdemeanor offenses, stalking, and temporary restraining orders. The Legislature, at the urging of the Honolulu Police Department, also became the first in the country to authorize county police departments to enroll firearms permit applicants and individuals who are registering their firearms into the federal Rap Back service. Under the federal Rap Back service, the reporting county police department will be alerted whenever a new record is entered for that applicant (i.e. conviction of a felony). In 2017, Hawai‘i began requiring the County Police Chiefs to report the names of individuals to certain law enforcement agencies whose permit applications are denied because the applicants are prohibited from purchasing or possessing a firearm under state or federal law (i.e. to the County Prosecutor for domestic abuse offense convictions).

Hawai‘i Firearms Law

Hawai‘i requires that a person acquire a permit from the county chief of police. An applicant must be 21 years old and a U.S. citizen. An applicant is fingerprinted and photographed and a criminal background check is conducted. Hawai‘i’s law disqualifies persons convicted of a federal crime, and any felony, or crime of violence, or an illegal sale of any drug, or acquitted or a crime because of mental disease, disorder or defect. The law also disqualifies people who are in or have been in treatment or counseling for addiction to, abuse of, or dependence of alcohol or drugs.

An applicant also needs to sign an affidavit regarding mental health and lack of drug or alcohol addiction or criminal background.

Under the Uyesugi law, the applicant also needs to authorize release of medical history and provide the name and address of a primary care physician, if the person has one. The applicant’s doctor is required to release any mental health information pertinent to acquiring firearms. A drunk driving record, history of serious psychiatric diagnosis, or any treatment for alcohol or drug abuse usually results in denial of a permit but a physician’s letter can establish that a person is “no longer adversely affected.”

The county policy must provide written notice of a disqualifying condition when a permit is denied. The applicant then has thirty days to transfer all firearms and ammunition to a dealer or other authorized person or turn them in to the police.

A successful applicant must wait fourteen days for an initial permit, and the police chief has the discretion to require that an applicant wait fourteen days for each subsequent permit. Each transaction requires a separate permit to acquire handguns and each permit must be used within ten days of issue. Permits to acquire shotguns and rifles are good for one year from the date of issue for any number of transactions. While there is no fee for permits, the Counties can charge a one time only fee (currently $16.50) for an FBI fingerprint check.

An applicant is also required to show evidence of safety training to get a permit which can be met through military pistol courses, law enforcement courses, a Hawai‘i Hunter Education Course, or a 6-hour course including 2 hours range time, instruction in Hawai‘i gun laws, and safe handling and storage, taught by an NRA certified instructor.

Hawai‘i’s firearms statute bans “assault pistols; automatic firearms; rifles with barrel lengths less than sixteen inches; shotguns with barrel lengths less than eighteen inches; cannons; mufflers, silencers, or devices for deadening or muffling the sound of discharged firearms; hand grenades, dynamite, blasting caps, bombs, or bombshells, or other explosives; or any type of ammunition or any projectile component thereof coated with teflon or any other similar coating designed primarily to enhance its capability to penetrate metal or pierce protective armor; and any type of ammunition or any projectile component thereof designed or intended to explode or segment upon impact with its target.” Further, Hawai‘i law also makes it a crime to “install[], remove[], or alter[] a firearm part with the intent to convert the firearm to an automatic firearm.” The Legislature is currently debating whether to clarify the law to specify that bump stocks and altering trigger mechanisms are covered by the ban. The Hawai‘i statute also prohibits “detachable ammunition magazines with a capacity in excess of ten rounds which are designed for or capable of use with a pistol.” The Hawai‘i law further regulates transportation and storage of firearms and ammunition.

Selected Hawai‘i Gun Legislation

2001

Act 252

Requires health care provider or public health authority to disclose health information to police for the purpose of evaluating fitness to acquire firearms.

2006

Act 27

Background checks required.

2010

Act 96

Prohibits person or government entity from seizing any firearm or ammunition under civil defense, emergency, or disaster relief powers, or during any civil defense emergency period or any time of national emergency or crisis, from any individual who is lawfully permitted to carry or possess the firearm or ammunition under part I of chapter 134, Hawaii Revised Statutes (HRS), and who carries, possesses, or uses the firearm or ammunition in a lawful manner. Prohibits suspension or revocation, under emergency powers, of permits or licenses lawfully acquired and maintained under part I of chapter 134, HRS.

2012

Act 205

Requires a police officer to order a person to have no contact with a family or household member for a twenty-four hour period, or longer if the incident occurs on the weekend, when a police officer has reasonable grounds to believe that there is probable danger of further physical abuse or harm to the family or household member. Requires a police officer to seize firearms and ammunition in such cases. (SB223 HD1) Act 301

Exempts National Rifle Association certified firearms instructors from absolute liability for injury or damage caused by discharge of their firearms during the course of providing firearms training at a firing range to persons seeking to acquire a firearms permit.

2013

Act 254

Requires county police departments under certain conditions to fingerprint, photograph, and perform background checks on individuals who wish to register a firearm that was procured out-of-state. Authorizes the police departments to assess a fee for conducting a fingerprint check and specifies the amount of the fee. Extends the time period for registering a firearm procured out-of-state for consistency with the time period for registering firearms obtained in or imported into the State.

Act 255

Amends the offenses of terroristic threatening in the first degree and robbery in the first degree to include the use of simulated firearms.

2014

Act 18

Allows the State and counties to perform criminal history record checks on employees, prospective employees, volunteers, and contractors whose positions allow them access to sensitive information, firearms for other than law enforcement purposes, and secured areas related to a traffic management center. Allows the counties to perform criminal history record checks prior to making an employment offer, and be exempt from the ten year look-back period, for prospective employees whose positions involve the handling or use of firearms for other than law enforcement purposes.

Act 87

Provides for a court-based relief program for persons federally prohibited from owning a firearm based on a finding of mental illness or civil commitment. Requires the courts to provide information relating to involuntary civil commitments to the Hawaii Criminal Justice Data Center to disclose to the Federal Bureau of Investigation National Instant Criminal Background Check System database for gun control purposes.

2016

Act 19

Requires the courts to provide information relating to adult guardianships to the Hawaii criminal justice data center to disclose to the Federal Bureau of Investigation National Instant Criminal Background Check System database for gun control purposes. Requires the Hawaii criminal justice data center to maintain orders of appointment or information from orders of appointment for use in firearms permitting and registration. Takes effect January 1, 2017.

Act 34

Includes misdemeanor offenses under chapter 134, Hawaii Revised Statutes, relating to firearms, ammunition, and dangerous weapons, to the offenses that disqualify retaken and reimprisoned parolees from provisions regarding reincarceration and credit for time served.

Act 108

Authorizes county police departments to enroll firearms applicants and individuals who are registering their firearms into a criminal record monitoring service used to alert police when an owner of a firearm is arrested for a criminal offense anywhere in the country. Authorizes the Hawaii Criminal Justice Data Center to access firearm registration data.

Act 109

Specifies that harassment by stalking and sexual assault are among the offenses that disqualify a person from owning, possessing, or controlling any firearm or ammunition.

Act 110

Requires firearms owners who have been disqualified from owning a firearm and ammunition due to a diagnosis of significant behavioral, emotional, or mental disorder, or due to emergency or involuntary hospitalization to a psychiatric facility, to immediately surrender their firearms and ammunition to the Chief of Police. Allows the Chief of Police to seize firearms and ammunition if a disqualified individual fails to surrender the firearms and ammunition after receiving written notice of the disqualification.

2017

Act 63

Requires written notice to certain law enforcement agencies, the court that issued a protective or restraining order on an applicant, and the applicant’s probation or parole officer, as applicable, upon the denial of a permit because of federal or state law.

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran is a graduate of Maui High School, Yale College, and Boalt Hall School of Law, the University of California at Berkeley. He practices commercial, civil and administrative law with Takitani Agaran & Jorgensen, LLLP. He is currently a State Senator for Central Maui, serving as Vice Chair of the Senate Ways and Means Committee in 2018. He previously served as chair of the House Judiciary Committee and chair of the Senate Judiciary and Labor Committee. Keith-Agaran served in Governor Benjamin Cayetano’s administration (where he was the first Filipino appointed as Chairperson of the State Land Board) and Mayor Alan Arakawa’s administration (as Director of Public Works and Environmental Management).