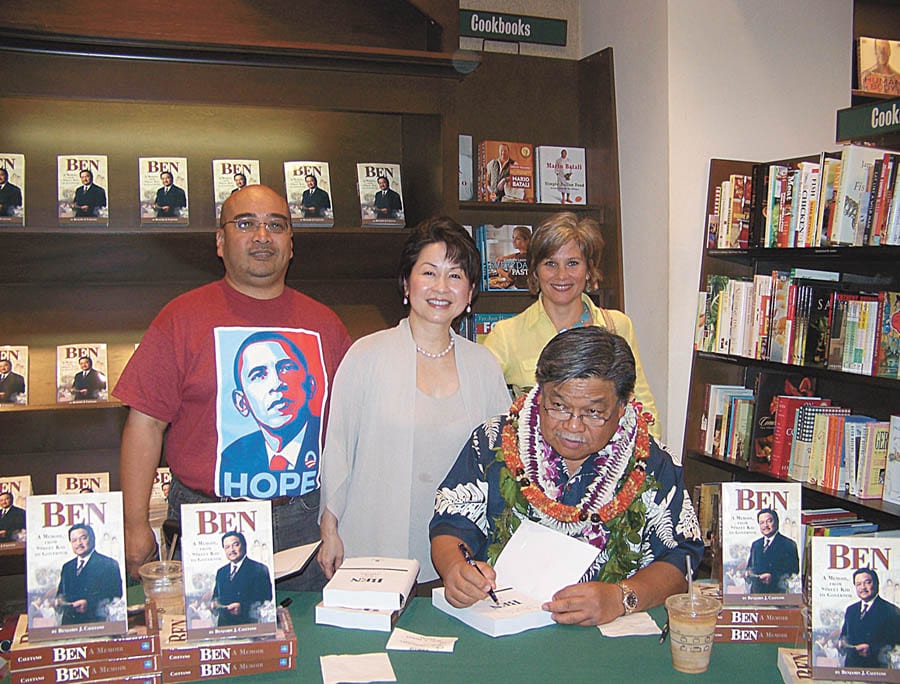

Benjamin Cayetano: First highest-ranking elected official of Filipino ancestry in the State of Hawai‘i.

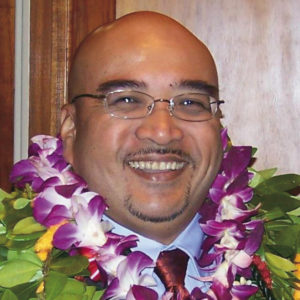

Gilbert S.C. Keith-Agaran

Photo courtesy Filipino Chamber of Commerce of Hawai‘i

Editor’s Note: 2019 marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the election of Benjamin J. Cayetano as the Fifth Governor of the State of Hawai‘i and the first Filipino-American elected as the head of an American state. This is the first of a series of articles profiling Cayetano and his historic election and service. Versions of these articles appeared previously in The Filipino Summit.

Near the end of his eight years as governor, when people asked Ben Cayetano about his place in Hawai‘i history, the Governor who grew up in working class Kalihi responded something to the effect that historians would need to make that evaluation. At the time, historians at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa likely would not have remembered his administration fondly. In 2009, Cayetano intruded on any evaluations from the Ivory Tower, completing Ben: A Memoir, From Street Kid to Governor. A blunt, opinionated and extremely readable autobiography about his life and his time in office, the Governor assessed many of the elected officials, bureaucrats, business people and Hawai‘i

residents that he worked with or against over the years.

As a contributor to the late lamented Filipino Summit, another Maui Filipino periodical, I recounted snippets of my own memories and lessons from those years. Keep in mind that I was a supporter and admirer and eventually worked for Governor Cayetano during his two terms (1995–2002). As a sub-Cabinet appointee for the first six years, I escaped being included in the index of characters discussed in Ben. I was appointed to the State legislature the year the book came out by the Republican who succeeded Cayetano as Governor, and some of my new colleagues who appeared in the index vented to me as the designated “Cayetano boy.”

The Art of Counting

In the legislature, counting is the basic skill required. In the State House, you needed twenty-six of the fifty-one members to organize and elect the House Speaker. In the State Senate, you needed thirteen of the twenty-five Senators to elect the Senate President. In your committee, you need at least half the members to move a bill out of committee and then half the members of your chamber to vote the issue out.

Cayetano, during his time in the legislature, would be on both sides of organizational fights. In 1984, the State Senate had one of those post-election internal organizational struggles that only political junkies love—where one group proves they can count to thirteen better than another. The losing group usually gets labeled as “dissidents.” Dissident from what, I never knew.

Cayetano and his closest allies found themselves among the dissidents when fellow Democrats re-organized around a short-lived coalition with liberal Republicans.

Apolitical Beginnings

Earl Anzai and Clayton Hee once quipped that to know Ben Cayetano is to love him. Anzai was a longtime aide to Cayetano in the legislature and after law school would go to work at Cayetano’s law firm. Hee served in the legislature with Cayetano before running for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs where he eventually became board chairman during the Cayetano Administration.

Unlike colleagues and supporters from his legislative days, I came to work for Governor Cayetano almost by happenstance.

I did not grow up in a politically active family.

I grew up in Pā‘ia, next door to Santos DeSoto’s livery stable on Luna Lane. I did not grow up wanting to be a political appointee or a government employee. The only Filipino names I recall in politics were Richard “Pablo” Caldito, Rick “Carabao” Medina and Claro Capili. My family—plantation and hotel folk—who managed to buy homes in lower Pā‘ia and Kahului—had little time for campaigning. They did some occasional sign waving but mainly they just voted. I can’t recall if my dad Manuel Coloma would tag along with his kinsman and kumpare Federico Pagdilao or his uncle Lloyd Labasan to campaign rallies but my dad was a loyal member of the ILWU Local 142. My grandfather, over shots of whiskey, would sometimes debate his friends about current issues after cooking for neighborhood parties.

I also knew of just a handful of Filipino lawyers—deputy prosecutor Artemio Baxa and private attorneys B. Martin Luna and Tony Ramil. But I wandered into law anyway since I hardly wanted to admit to my parents that my pricey American Intellectual History degree from Yale College required a vocational degree as well.

Around the time I was finishing college, another Maui High School graduate named Alfredo Evangelista had just passed the bar and gone to work for noted criminal defense lawyer David Schutter. My parents went to the same Aglipayan church as Alfredo’s and suggested I ask him about legal internships when I got into the University of California at Berkeley law school. Despite a heavy night clubbing schedule—Evangelista had a VIP card for infamous Waikīkī disco Scruples—the young bachelor managed to submit my name to the firm’s powers that be for a summer clerkship.

As a result, I worked that summer at Schutter Cayetano Playdon. At the Schutter firm, four of ten 1985 summer interns were Filipino-Americans: Dwayne Lerma, Jerry Villanueva, Norma Doctor Sparks and me. The others were all networking at the William S. Richardson School. At the time, we could list nearly all the Filipino lawyers in the State and those in law school both at U.H. and in the bay area, as well as the handful of sitting Judges of Filipino background.

As a result, I worked that summer at Schutter Cayetano Playdon. At the Schutter firm, four of ten 1985 summer interns were Filipino-Americans: Dwayne Lerma, Jerry Villanueva, Norma Doctor Sparks and me. The others were all networking at the William S. Richardson School. At the time, we could list nearly all the Filipino lawyers in the State and those in law school both at U.H. and in the bay area, as well as the handful of sitting Judges of Filipino background.

Before entering Berkeley, I never focused on the fact that Cayetano was one of the few Filipino lawyers in the state—I grabbed the internship because David Schutter was a top trial lawyer. I knew and admired Cayetano only as the fiery State Senator with the Prince Valiant haircut. As a young man, I had a firm distrust of the old Ariyoshi machine so I liked people like Ben who challenged the status quo.

Photo courtesy Alfredo Evangelista

Cayetano, to people who didn’t know him well, appeared gruff, and even aloof. He would never be accused of being the usual glad handing, baby kissing politician. Even after twelve years in the House and Senate, and although he had developed into a fairly good legislative debater, in 1986 Cayetano would remain somewhat guarded when meeting new people— very local in keeping his own counsel until he assessed where a person was coming from. For some, Cayetano waving a machete on the floor to punctuate his criticisms of then-Honolulu Prosecutor Charles Marsland formed their impression of the fiery young Filipino attorney. But he was good for a quote to the then-active Honolulu media covering the Capitol. Colorful and outspoken on the floor, Cayetano projected a dynamic image for local-born Filipinos. The Pearl City-Mililani Senator did not hesitate to offer his own strong views on issues that he had worked on.

To know Ben, is to love Ben.

In college on the East Coast from 1980–84, I had only fleeting glimpses of island politics. Freshman year, some tall ‘Iolani-hahvahd grad named Mufi Hanneman came up to New Haven to watch with us Yalies how Eileen Anderson upset Frank Fasi in a Democratic primary. On a trip to D.C. with the Yale Political Union, I ran into then-Congressman Cec Heftel’s office (the Hawaiian flag outside was a dead giveaway). Occasionally, my parents mailed some clippings about council elections.

My only vivid memory of Ben Cayetano that summer of 1985 was a four-legged race at the firm picnic. Ben was one of the senior lawyers to actually participate in the chance to make A activities. He did better than my team which fell for the first—but not the last time—just a couple of yards from the starting line. A then-rail thin Evangelista provided the middle legs flanked by senior partners Cayetano and Schutter.

Initiation

Nevertheless, while working on Maui the following summer Evangelista called on me to campaign for “Uncle Ben” who had decided to run for Lieutenant Governor. By the start of 1986, a number of the dissident Democratic Senators decided to move on. The Board of Education appointed former teacher Charles Toguchi as school superintendent. Dante Carpenter ran for Big Island mayor. Neil Abercrombie ran for Congress when Cec Heftel announced for governor against Lt. Gov. John Waihe‘e.

During the Chicago Bears Super Bowl, Ben mentioned to Anzai and Evangelista that he was mulling a race for higher office and needed a catchy slogan. The pair debated a number of possibilities throughout the game. That Monday, Anzai and Evangelista taped “Team Cayetano” on the State Senator’s door at the law firm.

Conventional political strategists advised the need for a “balanced” gubernatorial ticket so Chinatown odds makers touted the dissident Senator Cayetano as a possible running mate with Democratic frontrunner Heftel while former Honolulu Mayor Eileen Anderson balanced a pairing with the darkhorse Lt. Gov. Waihe‘e.

My only other campaign experience had been some canvassing for Gary Hart in New England and some volunteering for then-Lt. Gov. Jean King’s challenge to da Ariyoshi Machine. I don’t know if I would have actively campaigned for Ben if Evangelista had not coerced me into helping the Filipino Democrat. But my family liked the notion of a Filipino Lt. Gov. so my now retired parents, my grandfather, and my uncles and other relatives helped Evangelista’s Maui relatives sweep and paint the headquarters on Lower Main Street. It didn’t matter to the clan that Cayetano had never emphasized his Filipino roots and had been elected repeatedly from what people considered Americans of Japanese Ancestry (AJA) legislative districts.

My father and my grandfather simply noted that a Filipino campaigning for the state’s second highest elected post was an important symbol for our community. It also didn’t matter to us that the Lt. Gov.’s office didn’t have much to do other than to run elections and be Governor in waiting—not that prior holders of the office had been successful; except for Jack Burn’s handpicked successor George Ariyoshi, Lt. Govs. William Richardson, Tom Gill, Nelson Doi and Jean King never became Governor (Gill and King actually lost primaries against sitting Democratic Governors).

The 1986 primary was the first active work that my family put into any campaign. That summer and into the fall, we took turns spending time on the phones and writing friend-to-friend cards. Evangelista and I also escorted Cayetano—in his now iconic blue and white outfit—in the Makawao Rodeo Parade. We rode in the convertible while the candidate walked the route to shake hands with upcountry voters. Initially, Cayetano balked at walking the route behind the various pā‘ū riders but he appeared to enjoy interacting with the Maui residents lining the parade route.

I wasn’t home for the end of the Primary campaign but my parents recounted Ben quickly developed pretty good name recognition among the grassroots of the Filipino community. With some luck helped by the missteps of a candidate from another party, Cayetano upset the old guard favored Eileen Anderson. I was back at Berkeley in September when my parents called to tell me Ben had won. Although the team of conventional wisdom did not emerge from the primary, the Waihe‘e-Cayetano pairing won the 1986 general election, and Ben Cayetano was now the highest-ranking elected official of Filipino ancestry in the islands.

The New Dissidents

From my apartment in the Bay Area, I felt some pride that Ben had been elected but it wasn’t at the top of my agenda. I wanted to finish my final year, pass the California and Hawai‘i bar exams and get a job to repay my student loans. In retrospect, I think it ironic that Cayetano and his allies, in part, had sought other public service opportunities only when their continued contributions through the legislative process were blocked. I now realize the most skillful legislators serve many many years in the House and Senate, unknown to many outside of their own community. Many legislators are satisfied to work hard for the interests of their districts and the issues they find personally important, their ambitions checked by the risk of losing an election.

The officials who stand out to the greater public at large inevitably are those who take positions outside of the norm. Neil Abercrombie won the 1986 special election for Heftel’s seat but lost the Democratic primary to a young Mufi Hanneman; Abercrombie later won a Honolulu City Council seat before returning to Congress. Abercrombie would later re-take the Governor’s office for the Democrats after the Lingle interregnum. Carpenter served as Big Island mayor only to lose to an unlikely opponent several years later.

The officials who stand out to the greater public at large inevitably are those who take positions outside of the norm. Neil Abercrombie won the 1986 special election for Heftel’s seat but lost the Democratic primary to a young Mufi Hanneman; Abercrombie later won a Honolulu City Council seat before returning to Congress. Abercrombie would later re-take the Governor’s office for the Democrats after the Lingle interregnum. Carpenter served as Big Island mayor only to lose to an unlikely opponent several years later.

Toguchi and Cayetano would be involved in most of the major public issues for the next sixteen years.

At the turn of the century, the State House had a little shake up among the majority Democrats—some up and coming legislative leaders—Scott Saiki, Brian Schatz, K. Mark Takai and Sylvia Luke—couldn’t count to twenty-six and were replaced with other members from the Majority caucus. One of their colleagues, the great “dissident” Ed Case nearly won the 2002 gubernatorial primary against Cayetano’s Lt. Gov. Mazie Hirono. He later won the rural O‘ahu/Neighbor Island Congressional seat, lost a U.S. Senate primary, and in November 2018 won the Urban Honolulu Congressional seat. In 2013, Schatz was appointed to replace venerable Hawai‘i U.S. Senator Daniel K. Inouye, and Saiki and Luke re-took control of the State House. Takai would be elected to Congress the following year.